Synthetic antibodies constructed using bacterial superglue can neutralise potentially lethal viruses, according to a study published on April 21 in eLife.

The findings provide a new approach to preventing and treating infections of emerging viruses and could also potentially be used in therapeutics for other diseases.

Bunyaviruses are mainly carried by insects, such as mosquitoes, and can have devastating effects on animal and human health. The World Health Organization has included several of these viruses on the Blueprint list of pathogens likely to cause epidemics in humans in the face of absent or insufficient countermeasures.

"After vaccines, antiviral and antibody therapies are considered the most effective tools to fight emerging life-threatening virus infections," explains author Paul Wichgers Schreur, a senior scientist of Wageningen Bioveterinary Research, The Netherlands. "Specific antibodies called VHHs have shown great promise in neutralising a respiratory virus of infants. We investigated if the same antibodies could be effective against emerging bunyaviruses."

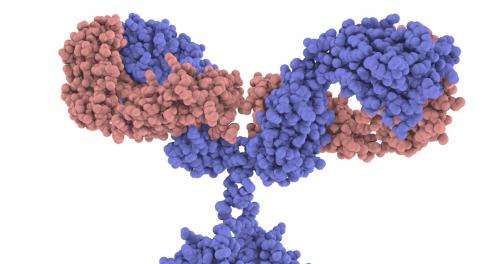

Antibodies naturally found in humans and most other animals are composed of four 'chains' - two heavy and two light. VHHs are the antigen-binding domains of heavy chain-only antibodies found in camelids and are fully functional as a single domain. This makes VHHs smaller and able to bind to pathogens in ways that human antibodies cannot. Furthermore, the single chain nature makes them perfect building blocks for the construction of multifunctional complexes.

In this study, the team immunised llamas with two prototypes of bunyaviruses, the Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) and the Schmallenberg virus (SBV), to generate VHHs that target an important part of the virus' infective machinery, the glycoprotein head. They found that RVFV and SBV VHHs recognised different regions within the glycoprotein structure.

When they tested whether the VHHs could neutralise the virus in a test tube, they found that single VHHs could not do the job. Combining two different VHHs had a slightly better neutralising effect against SBV, but this was not effective for RVFV. To address this, they used 'superglue' derived from bacteria to stick multiple VHHs together as a single antibody complex. The resulting VHH antibody complexes efficiently neutralised both viruses, but only if the VHHs in the complex targeted more than one region of the virus glycoprotein head.

Studies in mice with the best performing VHH antibody complexes showed that these complexes were able to prevent death. The number of viruses in the blood of the treated mice was also substantially reduced compared with the untreated animals.

To work in humans optimally, antibodies need to have all the effector functions of natural human antibodies. To this end, the team constructed llama-human chimeric antibodies. Administering a promising chimeric antibody to mice before infection prevented lethal disease in 80% of the animals, and treating them with the antibody after infection prevented mortality in 60%.

"We've harnessed the beneficial characteristics of VHHs in combination with bacterial superglues to develop highly potent virus neutralising complexes," concludes senior author Jeroen Kortekaas, Senior Scientist at Wageningen Bioveterinary Research, and Professor of the Laboratory of Virology, Wageningen University, The Netherlands. "Our approach could aid the development of therapeutics for bunyaviruses and other viral infections, as well as diseases including cancer."

More information: Paul J Wichgers Schreur et al, Multimeric single-domain antibody complexes protect against bunyavirus infections, eLife (2020). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.52716