Every time you open Instagram, Facebook is hoovering up your data. It knows where you're logging in from, whose stories you habitually watch, and which ads you linger on. That information helps Instagram's algorithm show you things you might like-and, more importantly for their business, things you might spend money on.

There's little you can do to keep an app from gleaning this data, but high schoolers have figured out one workaround to confuse social media algorithms. Samantha Mosley, a 17-year-old, presented at hacker convention ShmooCon about how she and her friends share a single Instagram account and peruse at their leisure. With their combined varied interests, Instagram knows less about who and where they are, and serves up a variety of content: sports, cooking, animals.

I was intrigued. I've long felt that the less social media companies know about me, the better. Facebook is confused about my gender and location, which it asks me about constantly, and I take great joy in looking through what it thinks I'm interested in for ad sales: Seal, the musician; Obsessed, a 2009 film I have never seen; categories like "human eye," "sock," and "knowledge." I jumped at the opportunity to fool Instagram, too, so I enlisted two Slate staffers to join me in a weeklong experiment in which we used the same Instagram account to see how our collective viewing changed the content or ads the app displayed.

As soon as my first co-conspirator logged on, I noticed a fewchanges.

We used an account I made in 2016 for my dog, which I had not logged into since. I'd followed a handful of my favorite Instagram dogs, so the "Explore" page, unsurprisingly, showed even more dogs, since that was basically the only interest that could be gleaned from my activity. Beyond that, the account was pretty much a blank slate for the three of us who'd be using it. There were no hard rules for the experiment besides to follow, like, search, and watch whatever you wanted.

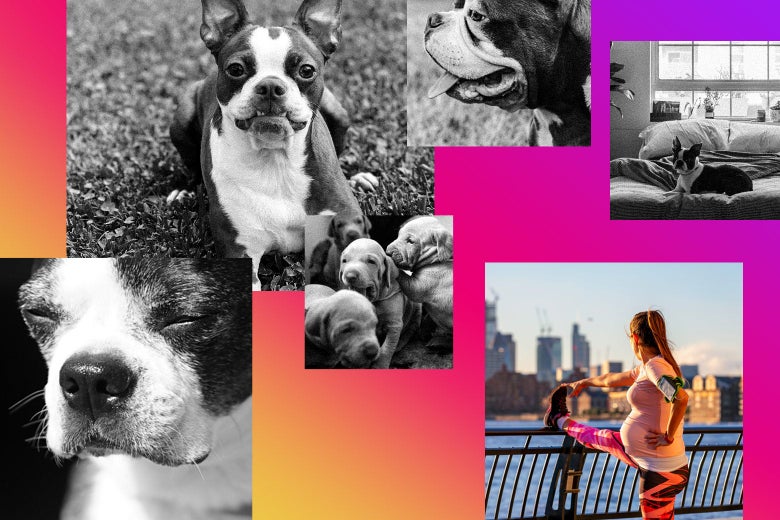

As soon as my first co-conspirator logged on, I noticed a few changes. While I initially started the account by following a few Boston terriers' and pit bulls' pages (I have a type), my colleague had followed a few other dogs of different breeds-a Samoyed, a beagle mix, and a black Lab, among others-and a rabbit account. Immediately, Instagram made use of this information by showing me a different assortment of animals on the account's "Explore" page; what used to be only Boston terriers now included bulldogs and Dalmatians. As we browsed, Instagram seamlessly molded the Explore page content; as I leaned into my fascination with The Bachelor, following a few of my favorite contestants from the past couple of seasons, Instagram added show spoilers and memes on the Explore page alongside the account's baseline content of dog videos.

A week later, things started to take off. The Explore page began to include recipes for vegan baked blueberry doughnuts, posts from pregnant fitness influencers, a side-by-side comparison of Robert Pattinson in 2005 and 2020, a photo of a chair designed to look like a scorpion, and a zit-popping video-all things I'd never expect to see based on what I usually look at online. In looking at Instagram's list of "ad interests" for the account, it appears our activity had added some new things to the list; while the original account had generated ads for dogs and pets, the post-experiment list now included some predictable additions like The Bachelor, food, and pop music, as well as some interesting ones, which I assume Instagram's algorithm must associate with the categories we viewed: divination and clairvoyance, pseudoscience, and Pitbull (the rapper).

At the end of the week, I didn't feel like I'd necessarily done much to really confuse Instagram-if anything, it now just had a wider variety of ads to show me and my collaborators, and data from three phones instead of one. But I did find an unexpected result: the thrill in seeing posts on the Explore page that the usual algorithm wouldn't have shown me. And when I saw these posts, I spent time with them. Rather than clicking on the usual dog photos, I gravitated toward posts with unfamiliar images: celebrities I didn't recognize, or exercise clips and meal plans. I knew I was not free of the algorithm, of course, but it was a joy to see even a fraction of the many things on Instagram I wouldn't normally come across.

A similar joy had struck me when I first joined TikTok. Without any knowledge about my interests, the app seemed to be showing me everything to see what might stick: old Japanese men dancing, magic tricks, artists who splattered paint on blank canvases, teen girls complaining about high school boys, stop motion animators. I was amazed by the abundance of creativity out there; who knew that there were metalsmiths recording their process, or people who used their access to an industrial-strength shredder to document the destruction of a jar of Nutella?

We talk about the "bubbles" social media creates-the sheltered dwellings each site confines us to, feeding us content it thinks we want to see. My blank-slate TikTok account let me peer into other subcultures' bubbles, which were all so much more interesting to me than what apps think I want to see. Eventually, TikTok learned my habits and the wacky content smoothed into cute animals and pranks. But while the novelty lasted, it reminded me of the internet of the late '90s and 2000s, when there were few "platforms," and no site on the internet tried to learn from your clicks. Rather, you just clicked around wandering the endless space, stumbling upon a new web comic, a page that displayed a random Vin Diesel fact upon each refresh, a repository of X-Files fan fiction.

The week after our shared-account experiment, I continued to use that Instagram account, and noticed that my co-conspirators' influence on the "Explore" page was waning. The algorithm tightened its focus again to mainly dogs and Bachelor memes, which meant I clicked on more dogs and Bachelor memes, until that's all that was left. In the end, I didn't feel like we'd confused Instagram and its data collection; rather, I felt like we'd outsmarted ourselves by, however briefly, reintroducing some serendipity in our daily browsing.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.