The first fixed-wing passenger electric aircraft took off from the Grant County international airport in Washington. The plane flew to 3,500 feet for eight minutes.

Northern Territory Air Services, a scheduled airline and charter operator, put in an order to bring 20 of the aircraft to Australia with plans to fly passengers from Darwin to Australia.

Australia is one of the most flight dependent countries in the world.

The Royal Flying Doctor Service, which operates the largest air fleet in the country and has traditionally been a hub of innovation, has no plans to acquire or develop electric aircraft.

A small group of companies have been working on electric flight.

Among them is the charter company Sydney Seaplanes, which is planning to become the first all-electric airline in the country, and Bader Aero, a company that is developing a two-seater electric aircraft.

Wisk, a US company, signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Council of Mayors of the state of QUEENSLAND to clear the way for its four-seater e VTOLs to operate as air taxis.

The sixth generation of Wisk's aircraft will have a range of up to 144 km, a cruising speed of up to 120 knots, and can be charged in 15 minutes. There are six propellors mounted on each wing. It flies in the air like a small plane.

Air taxis will be coming to Australia in a partnership with Air Services Australia.

Will these plans come to fruition? The regulations, insurance and infrastructure needed to make air taxis work are some of the things that need to be hammered out.

The proposals show that the discussion about aviation has started.

The aviation industry accounted for 2% of energy-related CO2 emissions in 2011. Domestic aviation accounted for 8% of transport emissions in Australia.

Qantas has begun discussing its plans to reach net zero emissions, beyond the usual carbon offset it offers its passengers.

The Qantas fleet burned almost 5 billion litres of jet fuel in the last year before the outbreak, and generated over 12 million tonnes of carbon dioxide.

At the launch of the company's climate action plan in April, the chief executive, Alan Joyce, stressed thathydrogen or electric powered aircraft are several decades away.

Qantas will replace its domestic fleet with sustainable aviation fuels from late in the 20th century. Qantas wants to use 10% of its fuel to be made with biological waste products or renewable materials by the year 2030.

Qantas helped create a $200 million fund to develop the industry.

They said that zero emission technology like electric aircraft or green hydrogen are far away for long-haul flights like London to Australia. The path to net zero requires high quality carbon offsetting to take place.

The price of fossil fuels is expected to go down, but the price of SAF fuels is expected to stay the same. There are concerns that the investment will create a new refining industry that may hinder the adoption of technologies that eliminate the need to burn fuel.

Virgin Australia has a commitment to net zero carbon emissions by 2050, but it is held back by a lack of domestic refining for SAF and electric aviation isn't something we're looking at for the time being

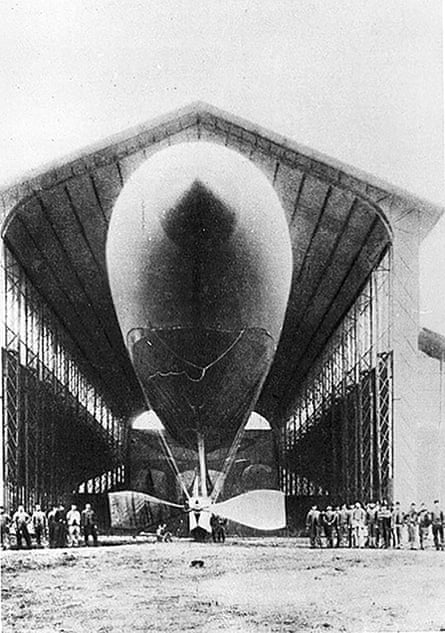

Weight is one of the main obstacles for long haul operators. Two decades before the Wright brothers first flight in 1903, a two-man crew took the airship La France on the first round trip by an aerial vehicle, carrying a 435 kilogram zinc-chlorine battery on its 8 km journey.

The power needed for a commercial passenger aircraft with 150 or more seats is only a fraction of the power provided by a modern battery.

In January, Prof Venkat Viswanathan wrote an article for Nature on the future of batteries in aviation which has become a call to arms for engineers in the industry. It was possible to make significant gains in battery chemistry for use in aviation by the year 2030. They wouldn't be able to power the biggest passenger aircraft.

Short-haul operators are the future of electric aviation in Australia.

The current generation of batteries are not a good solution and green hydrogen technology is not far enough along in its development to power flights even by light aircraft according to David Doral, the founder of Dovetail Electric Aviation.

He says that it has to be hydrogen. Is it possible to only use batteries? You won't fly very far.

Australia will be flying at two speeds, according to Doral.

We don't have a good solution for long-distance flying. The future on that side of the industry is not good. Short haul-aviation is a very different thing. There is going to be a renaissance of small operators.

The first passenger services in Australia were created after the first world war. Modern Australia wouldn't exist without cheap, commercial passenger air travel, says a professor.

Many things were changed by it. Australia was very important to aviation. We're a large country with a lot of people. There is no decent railway or motorway. We are very far from the rest of the world.

When people had to travel for six weeks on an ocean liner, the jet age made it hard to move large numbers of people.

As Australia faces the reality of climate change, electric flight promises to change how people move and where they live, create new industries and force a rethink of how cities are designed, according to the author.

We won't wake up tomorrow and have electric planes. There's a lot of potential there. If we have electric aircraft and vertical take off and landing, we will be able to travel more easily, and we will see more people working from more remote locations.

John Sharp is the deputy chairman of Rex Airlines and he believes in the potential for electric flight to break the hub-and-spoke model.

The company announced in August that it would be flying in 2024. One of its existing aircraft will be retrofitted with electric MagniX engines and a battery pack.

If the flight goes ahead, it will show that commercial electric flight is possible, as well as prepare the ground for the regulatory steps necessary to establish the industry.

There is a future for the whole concept of electric aircraft. It will be a blow for people who want to convert large aircraft to electric power if we can't.

Sharp said that success would be a game-changing event. Electric motor are less likely to go wrong as they have fewer parts.

If Rex didn't have to pay for fuel, more routes could be opened. He says it makes the un viable. We will be at the forefront of this. There is a lot of hope and a lot of expectations at risk.

The world calls on airlines to reduce their carbon emissions and we have to try and do something to meet that call.