The world's largest unreinforced concrete dome can be found in the Pantheon in Rome, which has stood the test of time. Scientists have been trying to figure out what makes the material last so long. There are manufacturing secrets hidden in the concrete walls of the Privernum archaeological site near Rome. According to a new paper in the journal Science Advances, the Romans used "hot mixing" with quicklime to give the material self-healing capabilities.

Like Portland cement, ancient Roman concrete was a mix of a semi-liquid mortar and aggregate. Portland cement is usually made by heating limestone and clay in a kiln. The best way to make Roman concrete is to ground it into a fine powder with just a touch of gypsum.

The Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius wrote a book about how to build concrete walls for funerary structures that could last a long time. He said the walls should be at least two feet thick and made of either red stone or bricks. The brick or volcanic rock aggregate should be bound with mortar made from hydrated lime and glass from volcanic eruptions.

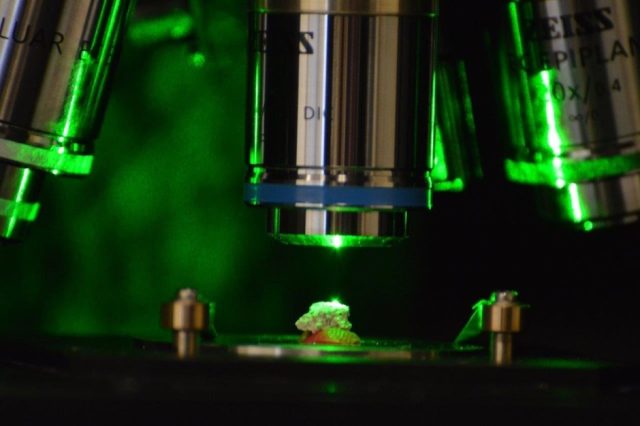

AdvertisementAdmir Masic is an environment engineer at MIT. Masic and two colleagues pioneered a new set of tools for analyzing Roman concrete samples from Privernum at multiple length scales.

The Tomb of Caecilia Metella, a noblewoman who lived in the first centuryCE, is located along the Appian Way in Rome. One of the best preserved monuments on the Appian Way is it. The Advanced Light Source was used to identify the minerals in the samples.

They found that the tomb's mortar was similar to the walls of the Markets of Trajan. The tephra used in the tomb's mortar was rich in leucite. The binding phase was changed by the presence of the dissolved mortar. After more than 2,000 years, some parts were still intact, while other areas appeared to have split. The structure looked a bit like nanocrystals. The interfacial zones evolve through long term remodeling.

Masic wanted to take a closer look at the strange white mineral chunks known as "lime clasts." Others had largely dismissed them as a result of subpar raw materials or poor mixing. The idea that the presence of these lime clasts was due to low quality control always bothered Masic. If the Romans put so much effort into making an outstanding construction material, following all of the detailed recipes that had been altered over the course of many centuries, why wouldn't they make a well-mixed final product? There needs to be more.

AdvertisementThe Romans were thought to have combined water and lime to make a paste. Masic suspected that they might have used the more reactive quicklime in combination with slaked lime because of the analysis done by the lab. There were different forms of calcium carbonate that formed at high temperatures.

The benefits of hot mixing are twofold. When the concrete is heated to high temperatures, they allow chemistries that are not possible if you only use slaked lime. The increased temperature allows for faster construction since all the reactions are accelerated.

It seems to give self-healing abilities. When cracks form in the concrete they are more likely to move through the lime clasts. A solution saturated with calcium can be produced by the clasts. The solution can either be recrystalized as calcium carbonate to fill the cracks or strengthened with pozzolanic components.

Evidence of cracks in Roman concrete was found by Masic and his team. They used ancient and modern recipes to create the concrete samples in the lab and then cracked them to make water. The cracks in the samples made with quicklime healed completely within two weeks, while the cracks in the samples without quicklime never healed.

Science Advances was published in 1992. About DOIs can be found in 10.1126/sci Adv.add 1602.