There is a scene in Tim Burton's 1993 animated feature The Nightmare Before Christmas where a little boy gets a shrunken head. The boy or his parents don't like it. When these objects were in high demand in the early 20th century, there was a lucrative market for fakes. shrunken heads, also known as tsantsas by the Shuar people, are included in many museums, but how can curators determine if they are authentic? According to the August paper, certain techniques can help.

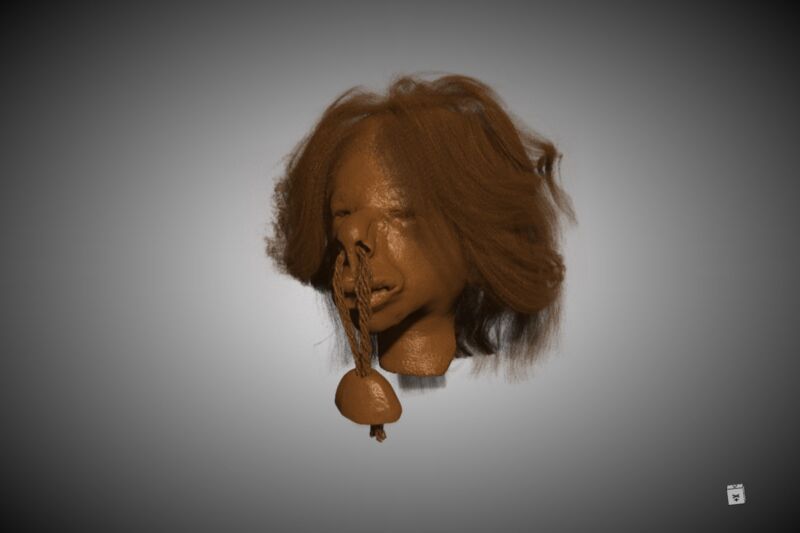

The practice of headhunting and making shrunken heads has mostly been documented in the northwestern part of the Amazon rainforest. The manufacturing process is the subject of differing accounts. The tsantsas were usually created by removing the skin and flesh from the skull and then throwing it away. There were red seeds in the nostrils and lips. The skin was boiled for 15 minutes to two hours so that the fat and grease wouldn't stick to the top. The skin became thin and contractile. The head was dried and molded back into something resembling a human, with the eyes closed. The skin was rubbed with charcoal ash in order to keep the avenging soul from escaping.

According to the authors of the August paper, the finished tsantas were not worn and were displayed on poles inside houses. The Shrunken heads were popular among Victorian-era priests, Europeans, and American explorers who wanted to bring exotic things back for their private collections. After 1860, a commercial market developed. Some of the tsantsas were made from human heads collected from dead people. They claimed their wares were legit.

AdvertisementAs many as 80% of the tsantsas currently kept in collections worldwide are commercial, and there are very few reliable methods to determine their true origin, according to Lauren September Poeta and her coauthors. The curators usually rely on visual inspections or computed toms for verification. There are four features that are poorly resolved using standardCT scanning. They wanted to see if they could improve the resolution of those features with a combination of micro-CT scanning andCT scanning.

A tsantsa from the collection of the Chatham-Kent Museum in Chatham, Ontario was used by the team. There was no proof that the Chatham tsantsa was the real article, and there was only one note of origin. The researchers used a machine at the Museum of Ontario Archaeology to do the scans.

The Chatham tsantsa is made of genuine human remains, but Poeta and her colleagues couldn't say if it was ceremonial or commercial. The rough cut at the back of the skull and double-hiding are consistent with the former, but modern thread was used to stitch the incision, eyes, and lips, which suggests commercial production. The practice of creating tsantsas likely exists on a spectrum rather than an either/ or dichotomy as the authors wrote.

Subjecting tsantsas of known provenance could be used to learn more. Micro-CT scanning can be used to determine whether a given tsantsas is made of human materials, and provide higher resolution details, according to the authors.

The article is titled "Posy One, 2022." About DOIs can be found in the journal's 10th edition.