From France to Indonesia and Australia, ancient life is painted across the walls of dark caves, seemingly motionless silhouettes that echo an earlier time.

In the past few years, archaeologists have imagined how these simple images may have captured moving scenes that we had not considered. It seems that animation has its roots in old art.

There was a series of stone engravings of strange animals with melded bodies. Using 3D models and virtual reality software to bring ancient etchings to life, the team of archeologists argued that the stone artworks could have been dynamic representations of animals in motion.

These prehistoric artworks inspire awe because our human desire to understand, represent and recreate movement runs deep.

The 'Burnt City' in southeast Iran was covered in ash and dust for hundreds of years. There is a goblet with burnt red sketches of a jumping goat that springs to life when the vase is spun.

The horned goat jumps up to eat the leaves of a tree that may represent the Assyrian tree of life. Archeologists only recognized the drawings years after the vase was unearthed.

The National Museum of Iran has a clay vase on display that is thought to be over 5,000 years old. Persian potters mastered early concepts of animation and persistence of vision long before 19th century inventors put two and two together.

"This is suggestive that humans had for thousands of years been fascinated by animal movement and had put energy into trying to capture a series of sequential images," says Leila Honari, a Persian animation and art scholar.

There are more examples of Palaeolithic artists breathing life into their artworks than we know.

The narrative scenes captured movement with repetition. The Chauvet Cave in France contains a hunting scene filled with horses and bison, as well as cave lions that come back to chase their prey. Around 32,000 years ago, it was dated.

Some 12,000 years ago, people on the island of Sulawesi painted panoramic scenes depicting supernatural beings wrangling buffalo, in what is believed to be the oldest story ever found.

Honari writes that the Burnt City's goblet shows the creator's knowledge of a series of images as a movement sequence.

"The ancient potter created 'key frames' that contain a very basic level of animation principals such as squash and stretch, anticipation and even timing and spacing' to create a vase that must be the result of years and years of trial and error experiments," Honari says.

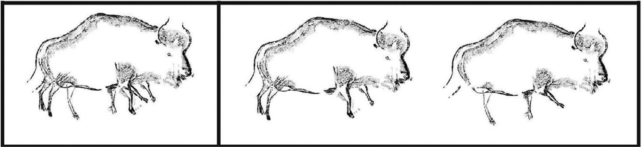

Body parts were captured in split- motion sketches. Stone etchings, which were described earlier this year, superimpose animal forms that appear, at first, to have one too many heads or more legs than normal.

The prehistoric drawings depict animals galloping along, tossing their head, or swatting their tails from side to side, similar to the sequence seen in flipbooks. A sense of motion is conveyed by barely sketched lines around the head and legs.

An eight-legged bison drawn in the Alcve des Lions in Chauvet Cave proves that split-action movement by superimposition was used from the Aurignacian period. When the light from a grease lamp or torch is moved along the length of the rock wall, it creates a graphic illusion.

Ancient bone discs and two-sided plaques may have been used to create visual illusions.

The artworks are still telling a story, one that we can only piece together at a distance. We can still marvel at ancient cave paintings that transport onlookers to other worlds long before our time and reorient our understanding of what it means to be human even if we don't use animation.