According to court documents, Gendron shot and killed a woman outside a Tops supermarket in Buffalo, New York, on a Saturday afternoon in May. If a manifesto published under his name is to be believed, Gendron might have noticed that some of her ancestors had golden skin and dark curly hair. He would have seen this as a sign of her character, since he had come to Buffalo to slay as many of them as he could.

A substitute teacher and a church deacon were killed by Gendron after he murdered Drury. He entered the store, killed the mother of a retired Buffalo fire commissioner, and shot a breast cancer survivor. The security guard was a former police officer. He killed a grandfather, a bus aide, a community activist, and a woman known for her baking before turning himself in. Gendron pleaded guilty to 10 counts of first degree murder and other charges brought against him by the state of New York, and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. There are federal charges related to hate crimes.

The Buffalo shooting was tragic but not unusual in the history of gun violence in the United States. A man opened fire at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, killing 21 people. More than 600 mass shootings have been documented by the Gun Violence Archive this year.

The Buffalo shooting has spurred some soul searching in the science community because Gendron cites dozens of peer-reviewed scientific studies as a reason for his white supremacist views.

The document references discredited studies that were published at the fringes of academia. A number of mainstream genetics studies have been published in prestigious academic journals. The studies do not directly address the question of racial difference, but they do explore themes that have interested race scientists for a long time. Several of the studies' authors told Undark that the findings of the studies were manipulated, misinterpreted, and distorted in order to give racism the sheen of scientific authority.

It's not unique to the manifesto that legitimate genetics research is appropriated for extremists. "I feel like these ideas are out there in our culture and science, and I'm not surprised to see someone leverage them in that way in a manifesto."

One person's distorted views are not reflected in the manifesto. It is an example of the spread of scientific racism, which has come to wield an alarming amount of influence in the far-right political arena.

Scientists have been interested in the question of how and why humans are different. Modern geneticists say that answering these questions could help deliver better medicine and other benefits. Many geneticists are considering the societal risks of their work and are concerned that some of their field's most common practices may serve to perpetuate the myth of race as a biological category and help fuel scientific racism.

Farina believes that there will always be people who misinterpret science to further racist agendas. She thinks that sometimes it's too easy for them.

For some in his field, the Buffalo shooting has elicited a very understandable moment of self- reflection. Is what we are doing correct?

To a time before the internet message boards, H ad Gendron could have found many examples of scientists and other people peddling the idea that humans can be divided into biological races.

You can sign up for Scientific American's newsletters.

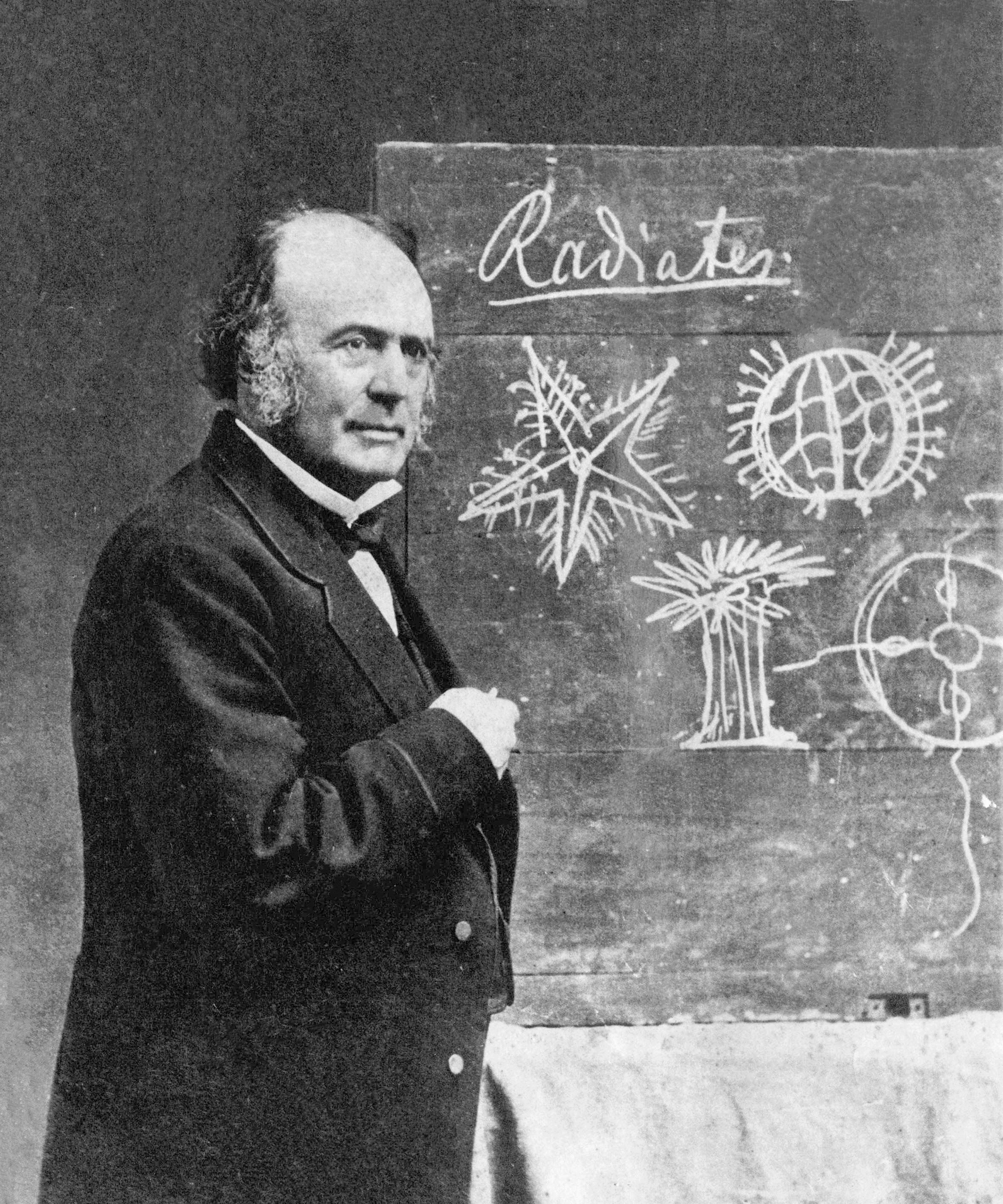

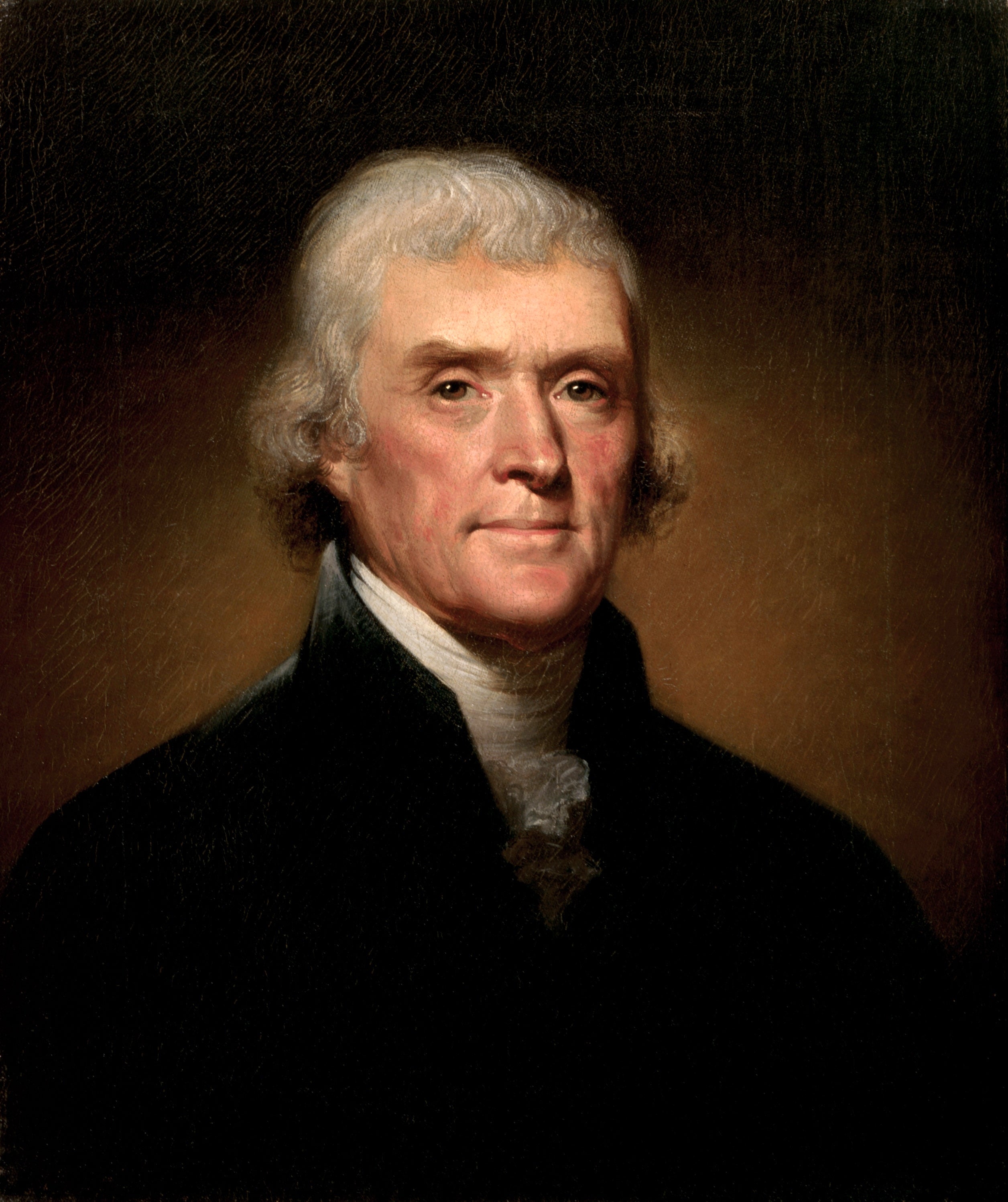

Arthur Jensen, a University of California, Berkeley psychologist, spoke to the California Advisory Council of Educational Research in 1967, saying that Black students suffered from genetic disadvantage to their White peers and that no amount of equality of opportunity or improvement of educational facilities could help them. He could have read about the 19th century Harvard professor Louis Agassiz, who told an audience in Charleston, South Carolina that the Black brain was that of a seven month old baby. He could have encountered one of his country's founding fathers, Thomas Jefferson, who speculated in the late 18th-century tome "Notes on the State of Virginia" that Black people were more likely to beinferior to the Whites in the endowments both of body and

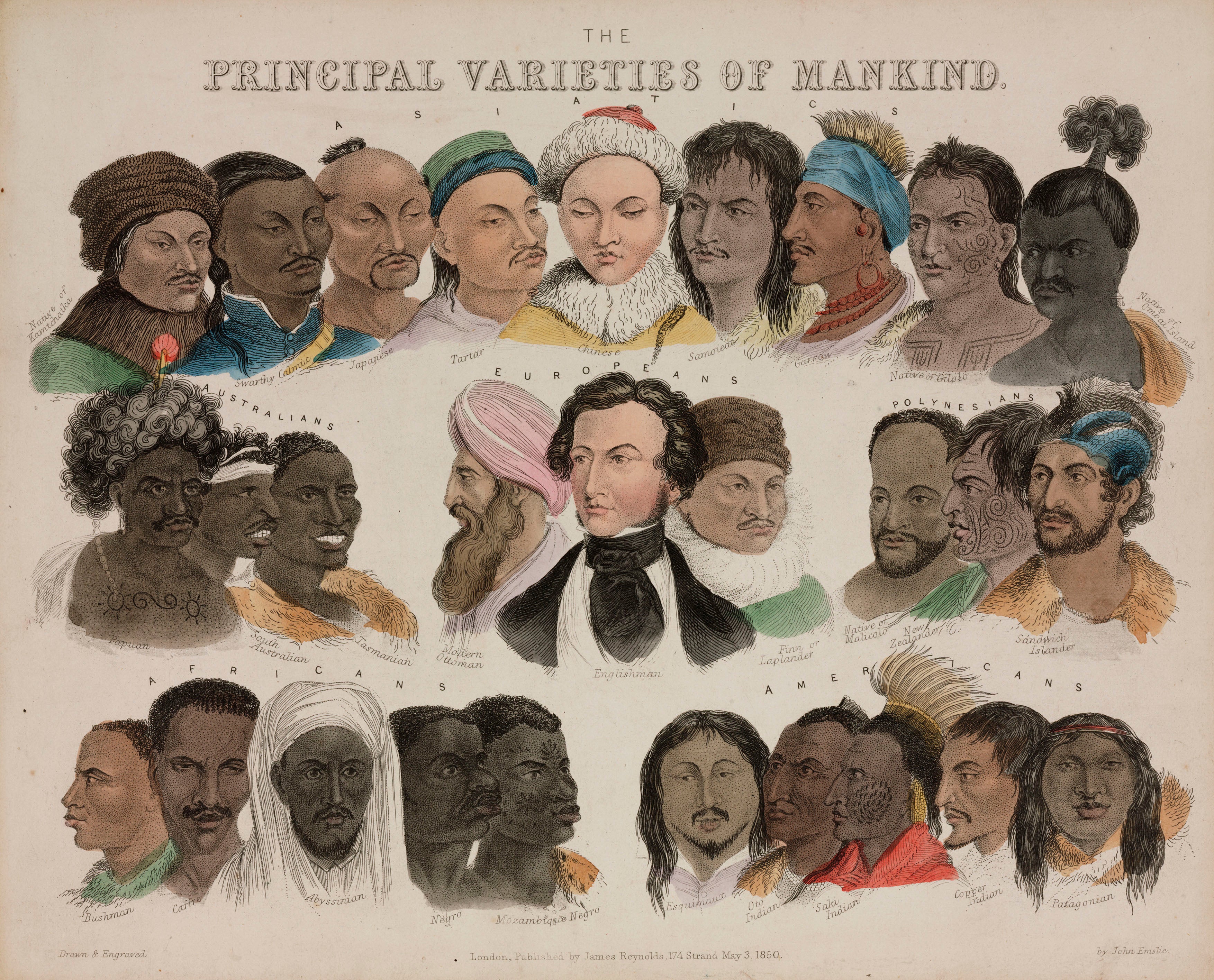

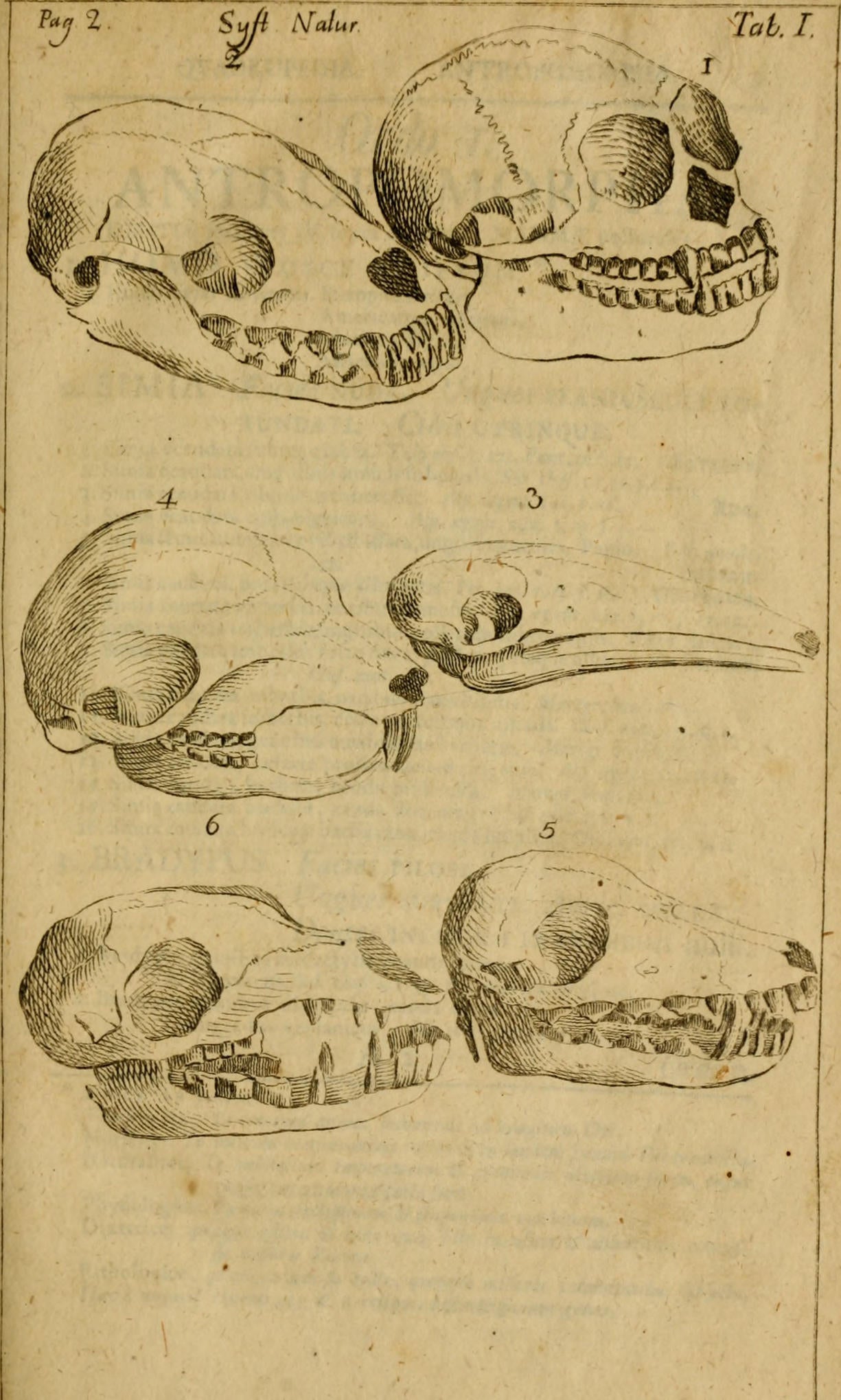

Had Gendron traced the idea of biological race all the way back to its beginnings, he would have found the writings of Carl Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist who is known as the father of taxonomy. Plants and non-human animals were the only classifications prior to Linnaeus. He broke with the tradition in 1735 in his book, "Systema Naturae," which divided humans into four groups at the top of the animal kingdom.

Andrew said that putting humans alongside other mammals was the big, big benchmark. This classification gave rise to a framework for the interpretation of human beings.

The French and German philosophers, as well as the German anthropologist, joined in the effort to arrange humankind into a natural order. Nicholas Hudson is a specialist in 18th-century literature at the University of British Columbia. In an era where the number of enslaved Africans being sent to the New World was increasing, the accounts that made their way back to Europe were usually written by people who were involved in the slave trade.

There was a porous line between fact and fiction. In his book, the author describes how a fictional English ship captain in a novel was mistaken for a factual traveller and used in his own scholarly writing.

Before the Enlightenment, the concept of racial classification had been practiced. Laws such as France's Code Noir, signed by Louis XIV in 1685, and hereditary slavery laws enacted in colonial Virginia in the 1660s had already put chattel slavery in the New World back in place. Many people came to see the savagery of the Indigenous Americans. Historians say that the naturalists of Europe were elevating old prejudices and political stereotypes into scientific orthodoxy by creating a Taxonomy for these differences.

The dividing lines were drawn by the end of the 18th century. The scheme proposed by Linnaeus mirrored the four races of four colors described by the author. Europeans first arrived in eastern Australia and Oceania.

Hudson wrote an essay in 1996 about the origins of racial classification. It appears to have its own color of human.

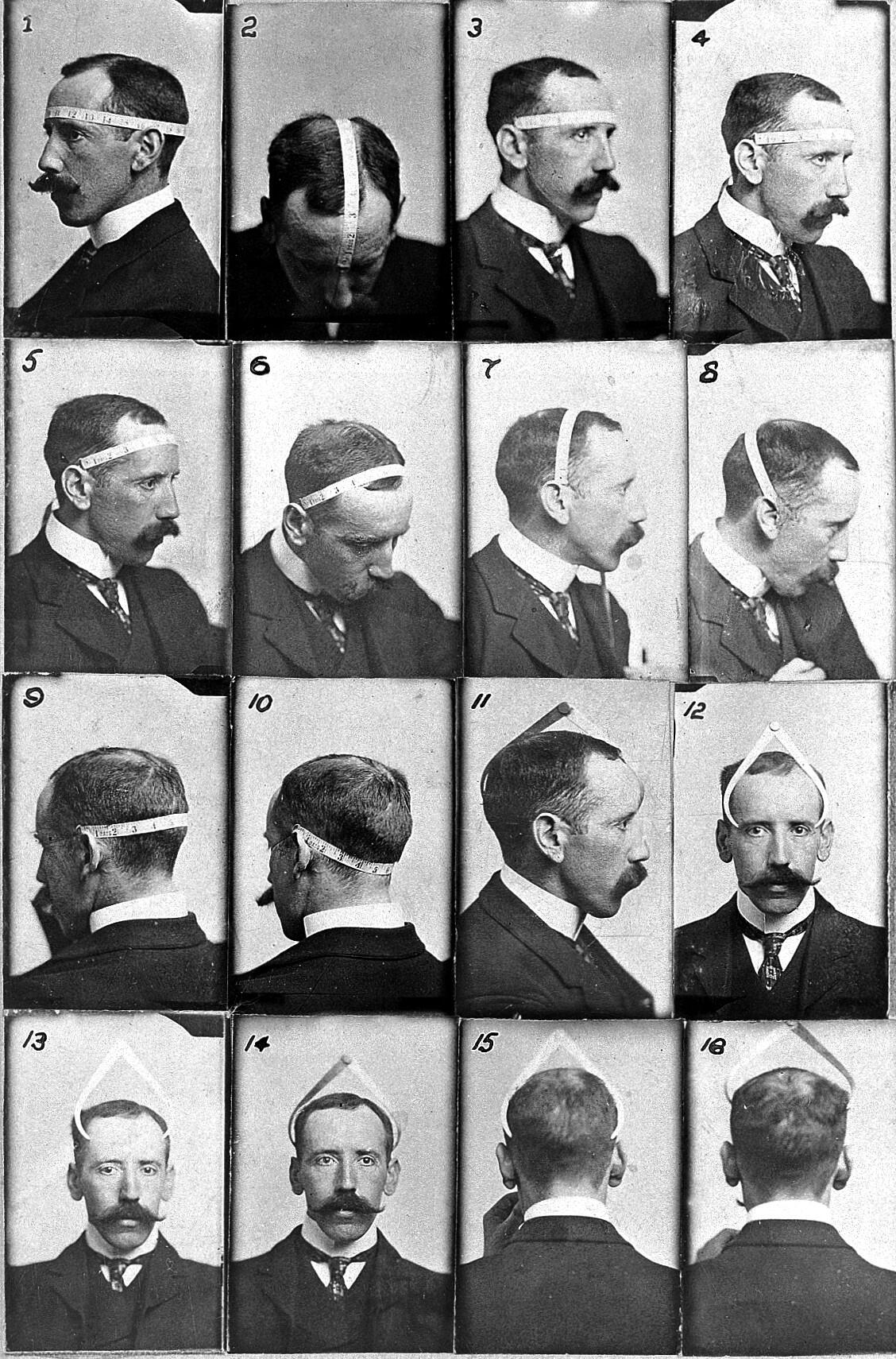

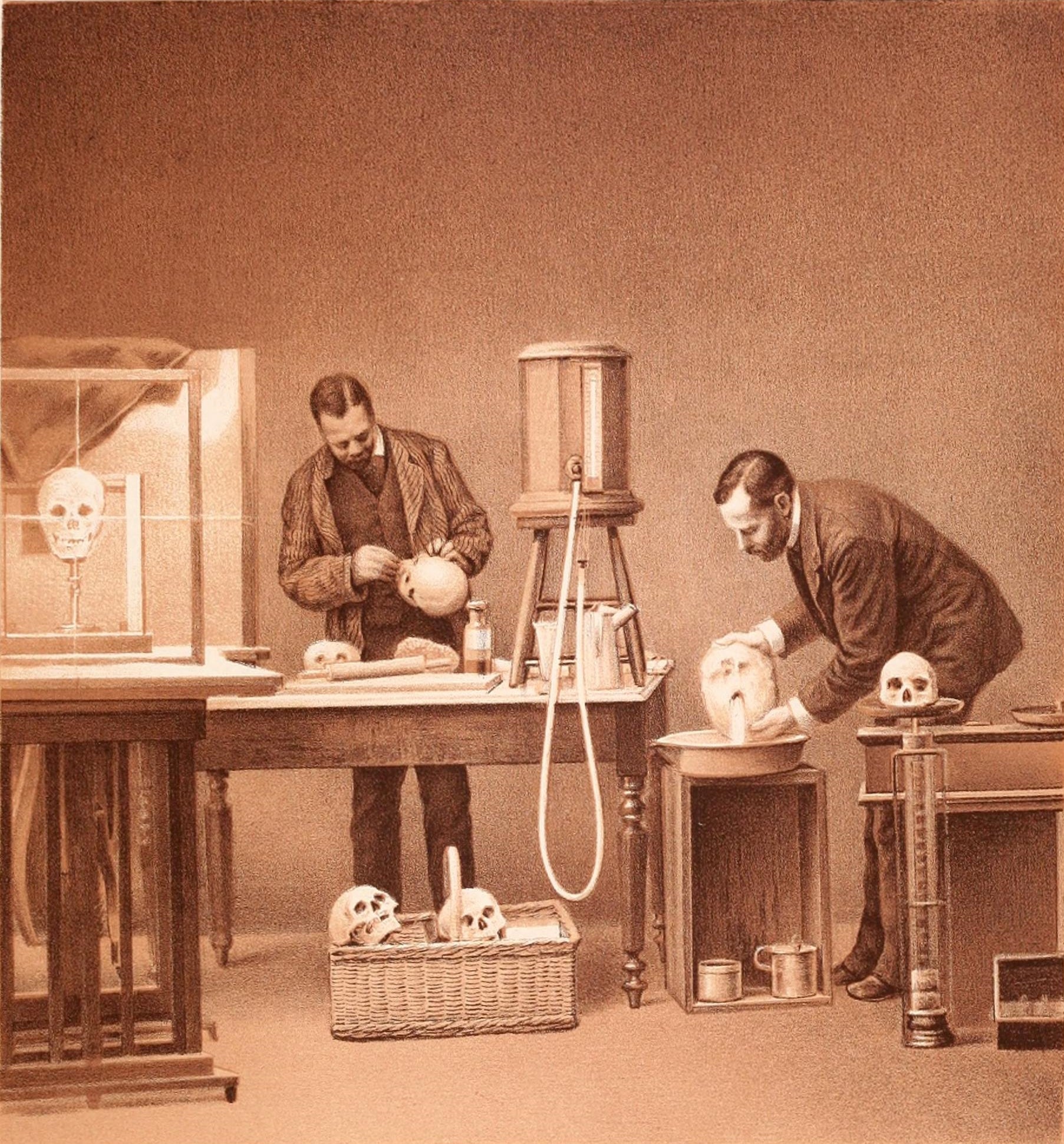

With race firmly ensconced in the scientific conscience, the rush began to confirm its divisions. In the decades that followed, anatomists, anthropologists, physicians, and others would scramble to try to affirm the new natural order. There are no fundamental truths of race unlocked by these investigations.

The idea of continental groupings as a reference frame for understanding human biological variation continued. Modern scientists mostly consider that notion to be problematic, but it still shapes practices in genetics research today.

Gendron recalls his first steps to becoming a racist when he started spending time on 4chan's "/pol/" imageboard in May of 2020. He wore the labels "white supremacist" and "racist" in the future. There is a lot of bar graphs, comic strips, and images that play on the stereotypes of race in the manifesto.

More than two dozen peer-reviewed science articles are cited as evidence of white superiority in the manifesto. The late psychologist J. Philippe Rushton's work was discredited by the university that once employed him, because his work was so flawed and error-ridden. A 2005 study that claimed to link a genetic variant to brain size is one of the mainstream research that has been challenged.

The research results are turned on their heads in other instances. Mark Thomas, an evolutionary geneticist at University College London, said that the 1998 study that claimed that a genetic variant linked to high IQ is common in Europeans was not true. He said that what was quoted was not said in the paper.

A lot of the content in the document is not new. Gendron pulled "prepackaged, meme-ified research objects" from various websites, and chunked them into his manifesto, according to a UCLA sociologist.

In a 2020 paper, Panofsky and two colleagues argued that these kinds of ready-to-share meme are a central plank of the human biodiversity movement. The movement has found receptive audiences among people in positions of power in the media. Scientists aligned with the movement have sought to use genetics to compare groups in order to find a genetic basis for their differences.

Mainstream geneticists don't like those kind of comparisons. The collection of genetic material, or genomes, of any two human beings selected at random from the rest of the world is small, they point out. The majority of the variation that distinguishes human beings is found between continental populations.

Daniel Benjamin, a UCLA professor who works at the intersection of economics and genetics, said that geneticists wouldn't be able to make the kind of racial comparisons that humans seek. It doesn't make sense to compare the frequencies of all genes within a group.

Benjamin explained that the reasons are technical and that the methods scientists use to tease out links between genes and traits are the reason. One of the most common approaches is a genome-wide association study, or GWAS, in which researchers comb the genomes of large populations and use statistical methods to try to identify allelics that influence a given trait. A typical GWAS might identify hundreds or thousands of alleles associated with a single trait, with each one affecting the trait to a different degree. A polygenic score is a number that attempts to predict how a trait will appear in any given individual, based on which of the associated all genes are present in the person's genetic code.

Polygenic score predictions are not perfect. About 40 percent of the variation in human height can be explained by genetic factors, but only 15 percent of the variation in coronary artery disease risk can be explained by genetic factors. The hope is that the scores can one day be used to estimate a person's risk of certain diseases based on their genetics.

Polygenic scores work best if they are applied to people who are similar to the original group. Polygenic score derived from a GWAS on one ancestry group to another can lose its predictive power when applied by researchers. Polygenic scores that perform well with people of British ancestry don't necessarily fare so well for people of Italian ancestry, according to studies. 40 to 40 percent of the observed variation in a population of European ancestry could be explained by a recent GWAS for height.

The limitation is referred to as the problem of portables. Geneticists don't know what causes it, but they theorize that it could be an artifact of certain genetic patterns that vary between ancestry groups. Benjamin said that GWAS results can't be meaningfully used to make the kind of between-group comparisons that race science enthusiasts are after. He said it was like comparing apples and oranges.

That is a reality that some proponents of race science would just as soon forget.

The site's /pol/ discussion board was a hive of activity after an anonymous user posted a message. The user said he couldn't do anything about the genetic evidence for racial differences. If someone here is a scientist, they should run the numbers and get their work published in order to save the world. Thousands of genes associated with intelligence are listed in the study.

The user was referring to a GWAS published in the journal Nature Genetics. The study sought to identify alleles linked not with intelligence, but with educational attainment, and what the authors identified as proxies for cognitive ability, including an individual's performance on a vocabulary test. The team identified a number of all genes associated with educational achievement and performance on cognitive and academic achievement tests. The group derived polygenic scores that could account for between 11 and 13 percent of the variation they observed in educational attainment.

When the researchers applied their polygenic score for educational attainment to people of African American ancestry, the predictive power plummeted. The researchers published a FAQ to explain why it wouldn't make sense to use their results to make racial comparisons.

Users on 4chan saw things in different ways that September. A user identified only as anarcho-capitalist created a scheme to cross reference the alleles identified in the Nature Genetics study with a publicly accessible catalog ofgenomic data called the 1,000 Genomes Project. Within two hours, the user had created and shared a table purporting to show 15 variant that were known to increase intelligence and that, according to the 1,000 genomes project, were more common in European ancestry groups than in African ancestry groups. The user wrote that the data was damning when it was checked. I only looked at one of the tables in the study. Over 200 genes like this can be found.

The flaws in the user's analysis would have been obvious to experts. Users of 4chan were enamored. One person replied in all caps. Before the references get shut down, download this and spread it.

The table was updated over the next five days. An anonymous user, also identifying as anarcho-Capitalist, posted an updated version of the original version that listed more than 200 alleles. The user claimed to have it. There are over 200 all genes that meet these requirements. The table would be reposted more than 500 times over the next four years.

An 18-year-old from rural New York state found a version of it and wrote a plan to kill as many Black people as possible in a grocery store.

Benjamin said he only learned of the table after the shooting. He said it was sad to see his work used that way. The table misrepresented our work.

R oberta Drury moved to Buffalo from the suburbs of Syracuse where she was raised with her adoptive family. Nancy Witt said that her half-brother was black and her mother was white. Both aspects of her heritage were embraced by her. In the wake of the shooting, news reports and law enforcement officials described the dead as Black.

State laws in the U.S. used to say that anyone with a single drop of Black blood was considered Black.

Race is a signifier, according to Stuart Hall. Its boundaries have changed under the influence of social, political, and economic forces. The way society sees a person is just as important as the way they see themselves. It isn't a hard concept. Panofsky said it was a slippery idea. There is a single scheme and a universal classification system that works for everyone, everywhere at all times, and you can slot all the people into it.

The fluid nature of race is one of the reasons why scholars don't study it as a biological variable in genetics studies.

Race is seen as a social variable that can affect health outcomes similar to household income or education level. Race has not been used as a genetic category in recent years. The term appeared in 22 percent of the American Journal of Human Genetics articles between 1949 and 1958, and just 4 percent of the articles between 2009 and 2018, according to an assessment of papers published in the journal in 2011. In 1993, racial categorization schemes were used in about 35 percent of Nature Genetics articles, but only 20 percent in 2009.

Race is often used as a shorthand for where a person's ancestors lived during a certain time in human history. Are you referring to the west of the Urals? Are you referring to the east of the Bering Strait?

Geneticists are using continental ancestry to categorize groups. A recent analysis, yet to be peer reviewed, found that continental labels were the most common type of label applied to ancestry groups. Africa, Europe, East Asia, South Asia, and the Americas are some of the 26 ethnic groups it collected data from. Questions about the study's use of continental categories were not answered by the principal investigator.

Continental ancestry categories serve as a proxy for defining a population of individuals who are genetically similar enough to be analyzed as a group.

Anna Lewis is concerned about the trend. She said that the danger is all of the problems that we have with race and how it gets used as a biological phenomenon. When people talk about ancestry categories, they tend to talk about continental ancestry categories. In this one-to-one way, those categories are mapped onto.

A group of 20 geneticists, bioethicists, historians of science, and others wrote an essay in the journal Science decrying the use of continental ancestry categories in genetics research. They wrote that systems of racial classification considered continents to be meaningful group boundaries. A misconception of race as a biological attribute will return through the back door when continental ancestry categories are used.

This back door may have given Gendron an opening to interpret the scientific studies in a racist way. Around half of the studies he referenced used race or racial labels. Continental ancestry groups were used by most of the others. Race was an easy to read subtext for Gendron.

C ritics of the use of continental categories in genetics point to the social dangers of reifying biological categories that align closely with popular notions of race, as well as the fact that a reliance on these categories holds back science. The practice gives the impression that these groups are a particular way of dividing up the human species, such that you capture something important about the structural variation. Jonathan Kaplan is a philosophy professor at the Oregon State University. He said that there are other ways to look at genetic variation in a different way.

It does a disservice to the people of Africa that they are lumped together into a single group.

"To refer to the African population is to refer to something that doesn't really exist, because it's aglomeration of several populations, each of which is as large as the ones they're being compared to."

The flow of genes over the course of human history has been shaped by regional differences. It has been influenced by a wide range of factors. Human genetic variation is based on location. Lewis said that it's patterned in other ways. At the end of the day, this is about who gets to have children with who. She said that researchers often privilege continental ancestry categories over other alternatives.

Many researchers believe that ancestry categories may not be necessary for many genetics studies. Rather than using geography as a proxy for shared ancestry or genetic similarity, researchers can use a statistical analysis of the information contained in people's genetic codes.

A group including computational biologists at the University of California, Los Angeles used a mathematical measure called genetic distance to test the ability of polygenic scores from a population of White British ancestry to be portable. By considering each person's genetic distance, rather than lumping them into continental groups, the researchers were able to pick up on nuances they might have missed. The polygenic score can be very similar for two people from different ancestry groups, but it can be different for two people from the same ancestry group.

Many geneticists believe that continental ancestry groups are far from homogeneity and that group averages may obscure details about the individuals who belong to them.

It is an example of how we don't need to divide humanity up and refer to any kind of population. It doesn't help us in terms of science.

White supremacists have been interested in Benjamin's work at the intersection of genetics and cognitive ability for a long time. White supremacists latched onto the idea that people of European ancestry are more intelligent than people of African ancestry despite the lack of evidence to support it.

Benjamin said that he was aware of conversations in white supremacist online communities about fringe science that was being written by people in the scientific community.

Funding agencies, including the National Institutes of Health, have supported the line of study. The agency is looking at the implications from this field of research and is aware of the capacity for genomic research to be an inspiration for revolutionary change as well as incredible, irreversible harm. Benjamin hopes that polygenic scores will one day be used to improve the analysis of social science experiments. The scores could be used in randomized studies in the same way that scientists try to control for family income or educational level. Researchers might be able to better estimate the effectiveness of interventions if they control for genetics.

The potential for their work to be misappropriated is something Benjamin and other researchers are aware of. He is part of a group of more than a dozen geneticists, bioethicists, social scientists, and science historians who are grappling with the societal implications of research in social and behavioral genomics. The group is looking at the ethics of the work and how to do it right. He said his group has taken steps to make sure their work is not misinterpreted. Anyone who wants to download their publicly available study data must first agree to an assortment of terms and conditions related to the ethical use of genetic data. The scientists have published lengthy FAQ's explaining why it is pointless to use their results to make racial comparisons.

Benjamin and his colleagues grouped people into continental populations in a study of more than three million people. They now use the term "European genetic ancestries" and "African genetic ancestries" instead of "European ancestry" and "African ancestry" to differentiate genetic ancestry from other forms of ancestry and to reflect the fact that a continental population consists of many different types of ancestry

Benjamin said in an email that he doesn't think continental groupings are necessary for doing GWAS studies, testing the portability of polygenic scores, or deployment of those scores in clinical settings. He said that he and other research groups have continued to use the categories because the alternative approaches are still being developed. There has been a need to standardize the analysis because large-scale GWAS have historically relied on massive collaborations. It is difficult for a lab to decide to try a new approach alone.

Lynn Jorde is a geneticist at the University of Utah. He said that using them made it easier to compare results.

Two papers that Jorde co-authored, published in 2007, and 2010, were cited in the Buffalo shooter's manifesto. The papers were misinterpreted in the document. He said that continental labels perpetuate a dangerous idea that humans can be divided into groups based on their geographical origin. The field is moving away from using continental groupings to compare. It is a healthy movement.

Continental categories are deeply entrenched in genetics research. She believes that moving away from the continental paradigm is just one of many important steps the field must take to do its work more responsible. She is part of a working group at Harvard that is trying to develop a framework for ethics in genetic ancestry research. She said that we need to think about potential harms, not just direct harms to research participants. Geneticists don't have good frameworks for thinking about that

The store where the Buffalo shooting happened is on the city's predominantly Black East Side, opposite three vacant lots at the intersection of Jefferson Avenue and Riley Street. The side of town that was scarred by racial dividing lines was the one that was most affected by the tragedy.

In a report on the state of Buffalo's Black communities, researchers at the University at Buffalo Center for Urban Studies described an East Side that has been undermined by systemic discrimination and neglect.

More than a third of Buffalo's Black residents have incomes below the poverty line, and less than a third own the homes they live in. In Erie County, home to Buffalo and its suburbs, approximately three in five Black residents die before the age of 75. Black residents are more likely to die early than any other ethnic group.

Modern genetics can be used to combat health problems that disproportionately plague Black communities such as those on Buffalo's East Side. Proponents of the research worry that it could be used as a tool of social justice. Major genetics studies mostly exclude people of color. According to one study, 78 percent of the individuals included in GWAS were identified as being of European ancestry; just 2 percent were of African ancestry, and a little over 1 percent of Hispanic or Latin American ancestry. The prediction tools that are currently emerging from the proliferation of GWAS and polygenic scores may be less useful to Black and Brown patients.

The focus on genetic solutions to public health and social problems may distract attention from the real drivers of these problems. If you want to solve the problem of the high maternal mortality rate in Black Americans, or the way in which Black Americans die seven years earlier than White Americans, then you should do that.

He said that the true drivers are socio- economic factors, legacies of racism, contemporary racism, and all the social determinants of health.

According to Kaplan, one of the big revelations of the GWAS era is that genes aren't as good as people think. He said there was an expectation that 50 percent of the variation in most quantifiable human behaviors would be explained by genetic inheritance. It is a terrible way to approach it because they are too weak to actually do that type of work.

It is not known if or when many of the loftier ambitions of large-scale genetics studies will come to fruition. He says that his intuition is that the work is going to lead to a cure for heart disease.

There was a makeshift memorial across the street from the Top's supermarket on Jefferson in May. There were appeals to community solidarity and Black Lives Matter written in chalk on the wall. The portraits of 10 people were put on the wall. The retired police officer was dressed in his uniform. There was a person in a hat.

Roberta was wearing a toothy grin and her dark hair was pulled back. Nancy Witt remembers the Roberta that she remembers. Witt said that she made her laugh whenever she cried. She was bright and smart. She had a personality that made her stand out.

I miss her a great deal.

The article was first published on Undark. The original article is worth a read.