The high mortality in the early stages of life is a common phenomenon in fish and other species, but it is not studied. The Center for Advanced Studies of Blanes and the University of Barcelona studied the mortality of the sharpsnout seabream, a species with an important commercial interest.

The results show that the survival of this fish in the first months is related to the time of birth.

The study is led by Marta Pascual, lecturer at the Faculty of Biology and member of the Biodiversity Research Institute (IRbio) of the University of Buffalo. The participants of the study are Carlos Carreras and Nuria Ravents.

The species has an ecological role.

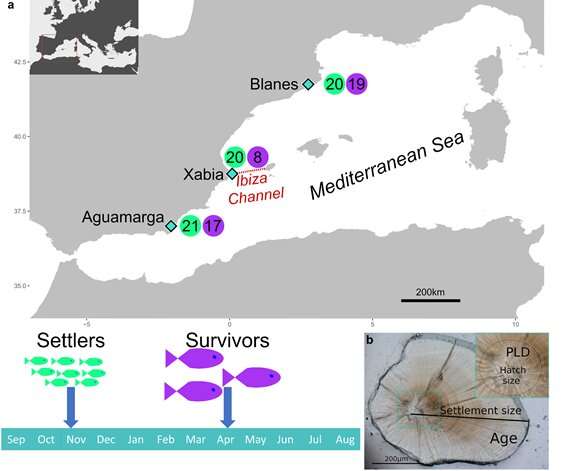

In the Mediterranean and the eastern Atlantic, the sharpsnout seabream is the only fish with a wide range of prey, including sponges. The researchers compared the data from recruits, individuals that only settled in October after being in the plankton, and survivors, six-month-old fish that had survived the winter.

A total of 105 individuals from three different populations were analyzed by the researchers. "Analyzing in three different populations the individuals that settle for the first time and those that survive allowed us to identify parallel evolutionary processes associated with environmental and phenotypical variables."

The analysis of the fish's otoliths, bones in the inner part of the ear, allowed for an inferred picture of the environment. "These are bone structures that show daily growth rings that allow us to see when it catches an individual, a series of variables like when it was born and its size, when it settled and what growth rate it will have or how many days it was in the plankton, they also allow

The people who survive are the people who are born later.

There were clear signs of mortality associated with birth time, sea surface temperature and growth rate. The individuals that survive the best are those that are born later, in cooler conditions, and grow slower.

122 genes were found to be associated with the same variables in three different populations. It supports the idea of a genetic basis for mortality during the first six months of life. The study is the first of its kind. They write that it's important to have this sampling as it shows that the results can't be decided by chance. We look at changes in the same direction when treating different populations.

The methodology is a new one.

A prototype for future studies of this and other species can be found in the methodology used in this study.

There are no studies that combine the methodologies and types of sampling. The study set the bases to analyze the survival in early stages in nature, to determine whether it is by chance or whether it is genetically determined, and to understand how polymorphisms are maintained in the populations in the presence of selection.

The genome of the sharpsnout seabream.

Although there is a high number of identified loci associated with these features, most of them have not been located in the closest available genome to the sharpsnout sea bream, which suggests that they are in poorly conserved regions.

One of the co-authors of the study, Carlos Carreras, has led a study by the Catalan Initiative for the Earth Biogenome Project to sequence the sharpsnout sea bream. "We hope that in the future, this will help us to identify where the genes are and the role they play in the survival of this species," they say.

Interannual variation studies can be done.

According to the researchers, there is an annual variation that can be very important when it comes to selection.

We want to know more because of the fact that we have found it. We are analyzing other years as well as obtaining the genome of the sharpsnout seabream. We want to see how parallel evolutionary processes change over time and see if there is local adaptation in each population. We want to identify candidate genes in which we can find out their functions.

There is more information about the Genomic basis for early-life mortality in sharpsnout sea bream.

Journal information: Scientific Reports