A breakthrough in nuclear fusion will be announced later today.

The National Ignition Facility is a laser complex in California. NIF has been unable to meet its stated goal of generating more energy than it consumes.

On December 5th, that changed. Researchers zapped a tiny pellet of hydrogen fuel with lasers. Sources familiar with the result say the energy out was much higher than the lasers put in.

The field of fusion science has been trying to reach this point for more than 50 years. One day fusion energy could provide safe and clean electricity.

Independent scientists don't think that dream is still many decades away.

Tony Roulstone, a nuclear engineer at Cambridge University in the UK, says fusion is unlikely to play a major role in power production before the 2060s.

Roulstone thinks the science is good. Engineering obstacles are still present. We don't know what the power plant looks like.

The Biden administration wants to bring America's net greenhouse gas emissions to zero by the year 2050, but fusion power won't be enough.

Nuclear scientists and engineers have been imagining fusion power for many years. An enormous amount of energy would be generated by the technology. Current nuclear "fission" technology is more efficient than the process that powers the sun. fusion would generate relatively little nuclear waste and run off hydrogen in the water.

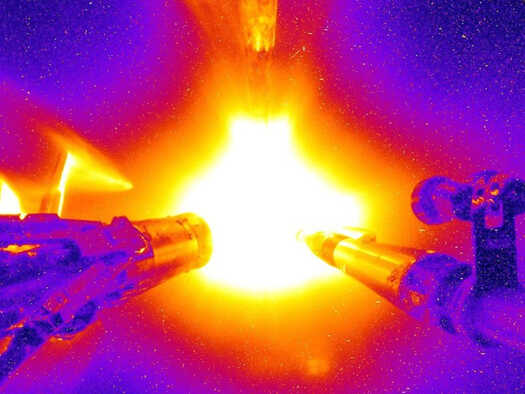

The NIF facility is the most powerful laser system on the planet. It is designed to aim 192 beams at a small cylinder. A small diamond capsule is inside the cylinder. There is a capsule filled with two different types of hydrogen that can release a lot of energy.

When the lasers are fired at the target, they produce x-rays that destroy the diamond. The hydrogen atoms are crushed by the shock of the diamond's destruction.

The initial laser shots were not as good as expected. The Department of Energy didn't have much to show for the billions it had invested in hydrogen.

Physicists were able to "ignite" the hydrogen inside the capsule in August of 2021. Betti is the chief scientist of the laboratory for laser energetics at the University of Rochester. "You start with a small spark, and then the spark gets bigger and bigger, and then the burn propagations through."

The process of self-burning is similar to that of a thermonuclear warhead.

The primary purpose of the NIF facility is to conduct very small-scale bangs that closely mimic nukes. Calculating whether the nation's nuclear weapons remain reliable despite decades on the shelf is helped by the data from these tiny explosions.

Betti, who holds a security clearance, wouldn't say how the ignition milestone would help physicists working on nuclear weapons, but he said it was very significant.

After last year's success, there was still one more goal to reach, which was to produce more power from the tiny capsule than the lasers put in.

According to sources familiar with the results, the facility has achieved that goal. Another exciting experiment was confirmed in a statement. Analysis is still going on. A press conference will be held on Tuesday morning.

Ryan is a nuclear engineer at the University of Michigan. That doesn't mean that NIF is making power. He says that the lasers need more than 300 megajoules of electricity to work. Even if the fusion reactions use more energy than the lasers, it is still only a small part of the total energy used.

It would take a long time to make enough energy to feed the grid. You would have to do this many times a second. One laser shot a week is how much NIF can do.

Arati is a nuclear scientist with the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory. The same amount of fusion fuel can run a power plant for years without emitting carbon dioxide. This is a great example of the possibilities. She says there are still many technical issues. It's a lot of work.

It's even harder to get economical power out of a fusion reactor. He and his team looked at another fusion technology called a tokamak and found that there were still many challenges to overcome. fusion will not be ready for the grid before the second half of this century, according to his analysis. He thinks the same time frame holds for the technology. He says it's difficult to see how you scale this into a power reactor.

The world will have to make drastic cuts to carbon emissions to avoid the worst effects of climate change by then, according to most climate experts. The world needs to cut its carbon output in half by the year 2030.

Betti agrees that the time it takes to build a fusion plant is long. He says that could change. He says there is always a chance of a breakthrough. The new results could help spur that breakthrough. If we can turn fusion into an energy-making system, you're going to get more people to look into it.

Rebecca Hersher is an NPR reporter.