Clinical care for people with blood disorders who need regular blood top-ups could be changed by a trial testing how long lab-grown red blood cells last.

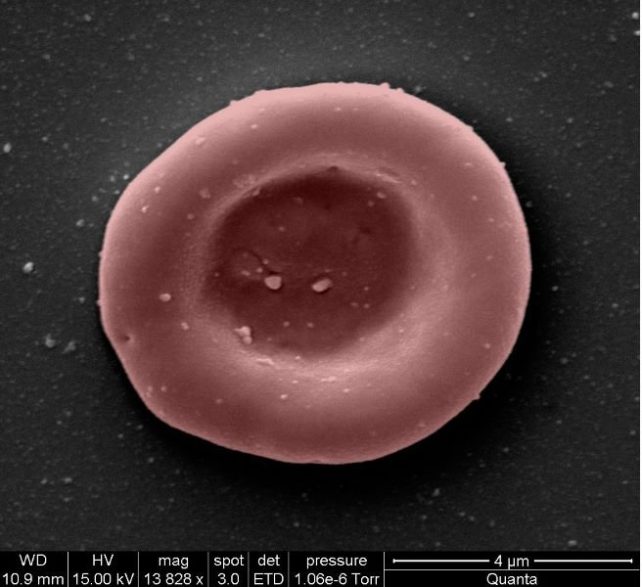

Red blood cells made in the laboratory are being studied to see if they last longer than blood cells made in the body.

One of the researchers working on the study says that the trial is a huge step in the right direction.

Stem cells from donated blood were isolated by the team of researchers and used to make red blood cells.

Researchers used to be able to transplant lab-grown blood cells into the same donor. Allogeneic transfusion is a process in which manufactured cells are infused into someone else.

According to a statement released last month, only two people have received lab-made red cells and there have been no reported side effects.

There will be at least eight participants who will receive at least two transfusions of blood. Red blood cells from a donor will be used in one of the transfusions, while stem cells from the same donor will be used in the other.

Once transfused into the bodies of healthy volunteers, the cells will be tracked as they whiz through the body's circulatory system until they are worn out, and recycled.

The lab-grown blood cells are all freshly made from donated stem cells, whereas a typical blood donation contains a swirling mix of new and months old blood cells, so the researchers are hopeful the manufactured cells will last longer. Studies suggest so.

A human red blood cell lasts about 120 days. If lab-grown cells can hold their own against donated blood cells, it could mean that patients who need blood more often won't need to give it up.

If the trial is successful, it will mean that patients who currently need long-term blood transfusions will need fewer in the future.

The lab-grown cells could be used to reduce the number of blood transfusions for those in need.

Patients with blood disorders, for example, need regular blood transfusions, relying on the goodwill of blood donors and good fortune to find the right match. In order to boost their oxygen levels, a person with the disease will receive blood transfusions.

Iron can accumulate in the body from multiple transfusions. The risk of accumulated iron could be reduced.

The risk of life-threatening immune reactions to specific donor blood groups could be lowered if fewer transfusions were done. Too many transfusions of one blood type can cause the body to produce an immune response.

Whether the process can be scaled up to produce more blood is one of the last questions.

Rebecca Cardigan is a clinical scientist at the University of Cambridge and she says that at the moment, they are only giving a small amount to their volunteers.

More research needs to be done to understand what happens when blood-derived stem cells stop making red cells.

"To go from here to a routine product for patients, there is obviously a lot more work that needs to be done that will take a long time," Cardigan says in the video below, where you can see how the cells are made.

If lab-grown cells prove to be safe and long- lasting, they could transform care for people with complex transfusion needs.

It's possible to make blood for people with ultra- rare blood types.

The medical director of the UK National Health Service's Blood and Transplant unit says the need for normal blood donations will not change.

The work could benefit patients with hard-to-transfuse diseases.