A new study shows how ancient civilizations in central Mexico may have used features of their rugged landscape to mark key points in the season, allowing them to plan the planting of crops needed to keep a thriving population of millions alive and well.

The research shows that the jagged horizon peaks of Mount Tlaloc could be used to monitor the agricultural calendar.

The Mexico Valley is warm and dry in the spring. It is monsoon season in the summer and autumn. Crops must be planted at specific times during the wet and dry season. The whole harvest can be undermined.

If the true rainy season doesn't continue, planting too early can be a disaster.

The corn field can be exposed to an overly short growing season if you wait to plant after the monsoon season has started.

The sun moves through the sky and a lot of civilizations use the horizon to see it. The oldest solar observatory in the world is composed of a line of stone towers that were built more than 2,300 years ago.

The passing of time is represented by the Sun rising or setting in the space between the towers. The exact time of year can be predicted by the huge clock.

The Basin of Mexico may have had a similar design. The Sun markers weren't built. They were picked from the natural landscape.

"In order to adjust their calendar, the Mexica would have needed to know the position of the Sun on certain dates of the solar year, a feat that could have been accomplished only by marking the sunrise (or sunset) bearing relative to a geographic landmark."

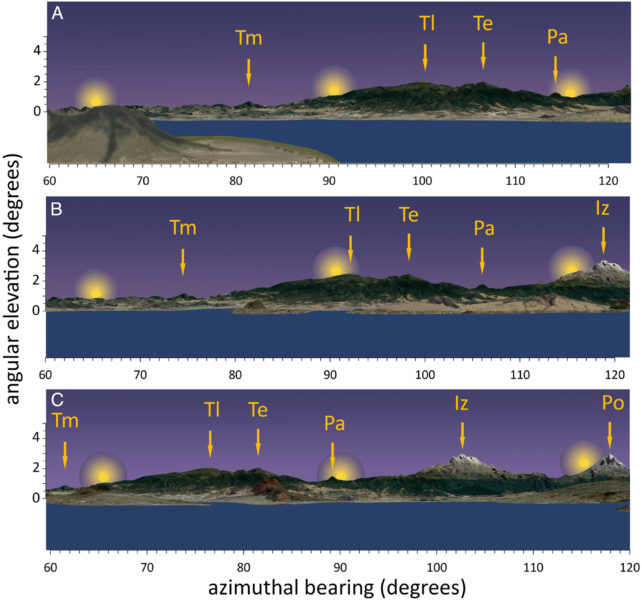

Mexico City's sacred Templo Mayor would have been designed so that the sun could be seen from a fixed point as it crosses the horizon. Mount Tepeyac might have been an alternative lookout.

While standing on the top of Templo Mayor, an observer could see the sun setting behind Mount Tehuicocone. The sun rises behind the archeological site of Tepetlaoxtoc, which is 2,300 meters above sea level, on the summer solstice.

The sun's progress along the horizon would be paused for a period of around 10 days during the summer.

The top of Templo Mayor is where the equinoxes are likely to have taken place. The March and September equinoxes are marked by the sun's rise behind Mount Tlaloc.

It is a highly accurate way of timekeeping because there is only one day in spring and one day in fall when the sun rises behind this mountain.

The alignments, along with illustrations and texts found in ancient Mexica codices, suggest that Mount Tlaloc was a fundamental tool for marking important times of the year. Every four years, an extra day would have to be accounted for in order to keep the calendar on track.

It's not clear whether ancient people in the Mexico Valley used this technique or not.

The Aztec calendar starts in February, but some historical records suggest that important rituals and sacred ceremonies took place at the same time as the sun rises.

The sun rises behind Mount Tlaloc during the driest part of the spring equinox.

Salt and summer corn are celebrated when the sun rises behind the salty shores of Lake Texcoco.

The winter equinox happens when the Sun rises at the edge of a landscape feature that looks like a sleeping woman. The time of year is associated with womanhood.

How might the Sun's position be used as a marker for the beginning of the year?

There is a raised road leading up the mountain's slope. In the image below, you can see that the road is built at a shallow angle, leading out of a rectangular enclosure.

The Sun sets right between the walls bordering the road when you look upslope.

The beginning of the Mexica solar year occurs when the Sun is framed in this beautiful way.

The people in the Basin of Mexico were able to maintain an extremely precise calendar by using systematic observations of sunrise against the eastern mountains of the Basin of Mexico.

The study was published in a peer reviewed journal.