Protesters took to the streets of Urumqi a week ago to protest China's zero-COVID policy. There was a big wave of protest on Chinese social media that night. Users uploaded videos of the demonstrators and songs like "Do You Hear the People Sing" from Les Misérables.

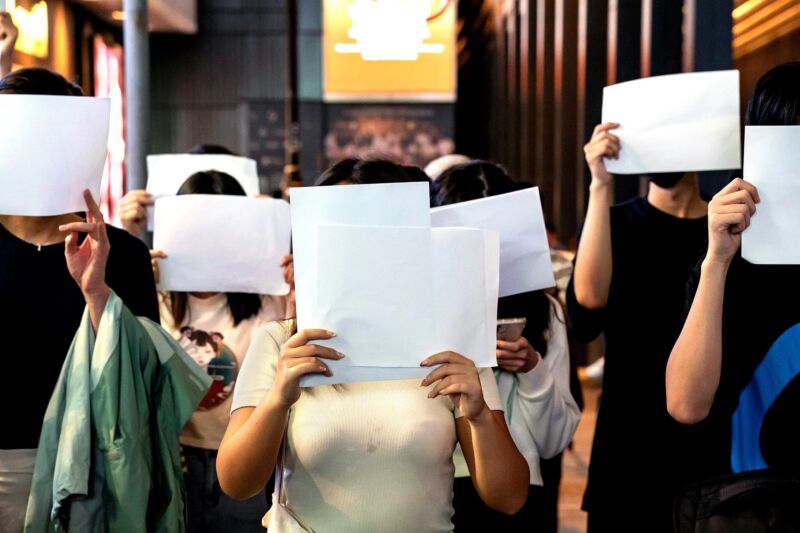

Protests spread after that. A crowd of masked people held up blank sheets of paper and called for an end to COVID policies. Protesters at Tsinghua University held up copies of the Friedmann equation because it sounded like a free man. Similar scenes played out in cities and college campuses across China in a wave of protest that has been compared to the 1989 student movement that ended in bloodshed.

One British national who has lived in Beijing for more than a decade, who asked not to be named, said that the mood on the messaging service was unlike anything he had ever experienced before. As people became bolder and bolder with every post, they seemed to be testing the government and their own boundaries. He saw posts that were different from the ones he had seen before on China's tightly controlled Internet.

Many Chinese people know how to skirt Internet controls and build up a sense of what will and won't be allowed. As the protests spread, one tech worker in Guangzhou said that younger users of the messaging service seemed to become unconcerned with the consequences of their posts. He didn't want to be named because of the danger of government attention. More seasoned organizers used apps like Telegram to spread the word.

The anti-lockdown demonstrations started as a way to honor the victims of the Urumqi fire. The city had been under a COVID lock down for more than 100 days, which some believe slowed emergency responders. The majority of the victims were members of the Uyghur ethnic minority who have been subject to a campaign of forced assimilation.

The tragedy came at a time when the number of zero-COVID policies was increasing. There were violent confrontations between workers and security at the factory. Scott Kennedy, of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank in Washington, DC, says that when he visited Beijing and Shanghai in September and October, it was clear that people had grown weary of the measures that were being taken. Kennedy thinks things have boiled over. He says the Urumqi fire and news that COVID cases were rising again pushed people over the edge.