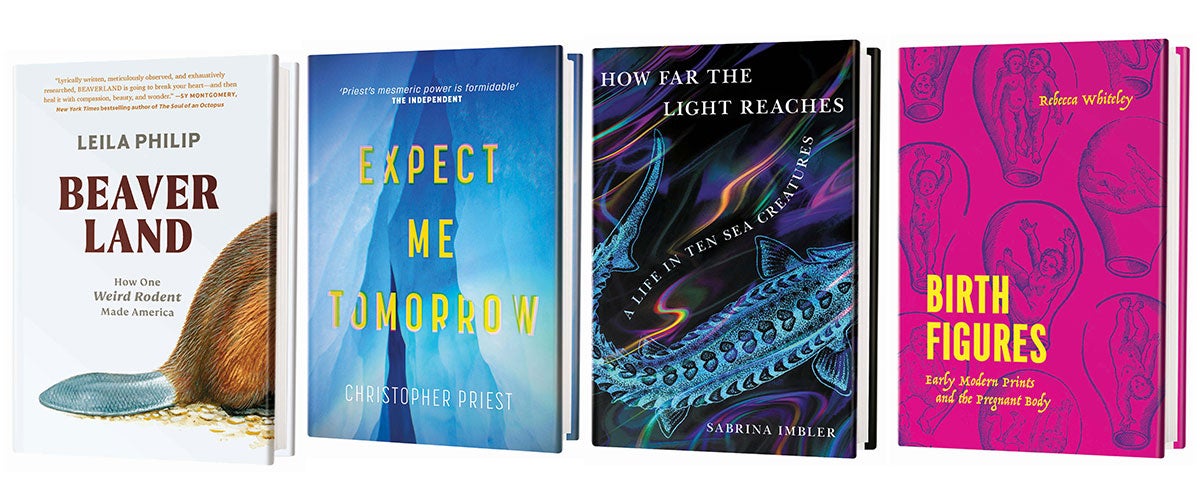

The influence of one weird rodents, an ecological thriller, and tender essays on deep-sea creatures are some of the books out this month. America's shape was not just its ecology. Beaverland: How One Weird Rodent Made America

by Leila Philip

Twelve, 2022 ($30)

They are having a moment. The engineers build dams that form ponds, which in turn filters out water pollution, sequesters carbon, and gives wildlife habitat. The Los Angeles Times and the New York Times both referred to the animal as a superhero. Some researchers want the U.S. Forest Service to replace the mascots of mammals with ones that are better at fighting mega fires.

Western science is learning from what North America's Indigenous people have known for thousands of years. The Blackfeet were so fond of the beavers that they forbade them from being killed. People are drawn to bournes because of their unusual features, such as their webbed hind feet and disproportionate hands. In her new book, the author writes that this is an element of the sacred in the beaver. It's no wonder that the human imagination is stimulated in every continent by the presence of the beaver.

Humans and castorkind have always been close. Some Indigenous tribes carved their teeth into dice and used their scapulae to dig. The scent glands with which the beavers mark their territories were especially coveted. If you like ice cream and pudding, you might have eaten a mammal.

The most valuable commodities of the beavers were their furs. The subtitle is "How One Weird Rodent Made America". John Jacob Astor, the country's first multimillionaire, lined his pockets as a result of the fur trade. The fur trade destroyed wetlands. Philip writes that before 1600, all of the continent from west to east, save a few desert sections, had stretched out as one greatBeaverland.

The rodents have made a remarkable recovery despite not fully returning to their former glory. The farmhouse in upstate New York was once home to colonies of semidomestic beavers. They used to chew the legs off the furniture. She goes to a forest in New Hampshire where scientists are studying the hydrology of rebuilt beaver meadow, which is said to have giant underground sponges that can absorb and hold large stores of water.

Philip is a big fan of modern fur trappers. Some trappers make a living killing beavers at the request of agencies and owners who worry that expanding ponds will damage private property. Philip is respectful of trappers' knowledge of beaver behavior, but still skeptical about whether lethal control is the best way to solve conflicts. Instead of using traps, it is better to use pipe systems that partially drain impoundments.

The rise of capitalism, the transformation of American landscapes and the fight against climate change are just a few of the enormous themes that are linked to the writing of a book about a mammal. Philip admits that he was being led astray by the beasts. A documentary about naked mole rats, the history of New England's stone walls and a documentary about coyote ecology are just some of the things we're given.

A book about beavers can sometimes spill beyond the banks. Some of Animalia's most unruly members are the boas, who force rivers to overflow, transform single- channel streams into braided ones and sabotage our precious infrastructure. We need to embrace their glorious chaos again.

Scott McGill is a stream restorationist in Maryland who works with animals to capture pollutants that would otherwise go into the bay. It would cost two million dollars to build a pond with that type of water retention. It was built for free by the rodents.

You can sign up for Scientific American's newsletters.

The winner of the PEN/ E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award is Ben Goldfarb.

Building tension but not empathizing.

Expect Me Tomorrow by Christopher Priest

Mobius, 2022 ($26.99)

Christopher Priest has created a number of high-concept thrillers, including The Separation, The Islanders, and the World Fantasy Award-winning The Prestige. In his new epic, Expect Me Tomorrow, he follows three interwoven lives that span both generations and continents. Adler Beck, a glaciologist who struggles to study the shifts in Earth's climate amid increasingly disabling events in the late 1800s, is one of three people.

Priest is an expert at changing his writing style to fit the topic. The paranoia and tension of a sci-fi thriller can be seen in Ramsey's sections, whereas Beck's sections have the same qualities. The danger of a changing climate and the shared histories of the characters are at the center of the various narrative threads.

The approaching ecological catastrophe is a constant drumbeat throughout the novel, but it is often far from the lives of the characters. Readers are exposed to future water wars, refugee crises and worsening storm cells through news reports. Rarely do they get to see how climate change is felt in the lives of the characters. Questions about the purpose of eco-fiction in our modern era are caused by this disconnection. Is the goal to assert the existence of our world's most pressing problem, or is the genre responsible for helping the people who will suffer the most from this coming disaster? Priest gives pages of scientific explanations of glaciology and the Year Without a Summer in 1816, but it doesn't develop an emotional core.

Climate change is often used as a plot hook in Expect Me Tomorrow, despite how compelling it is to read.

How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures by Sabrina Imbler

Little, Brown, 2022 ($27)

In her new book, journalist Sabrina Imbler looks at her life through the lens of marine biology. Their essays about the lives of aquatic animals give a glimpse into Imbler's life on land. The yeti crab is not a forced metaphor but a starting point for a deeper exploration of Imbler's family, sexuality, gender, race and relationships. The analyses show the joys and responsibilities we have as creatures with a complex brain.

Birth Figures: Early Modern Prints and the Pregnant Body by Rebecca Whiteley

University of Chicago Press, 2022 ($49)

In this fascinating porthole into English pregnancy culture in the 16th to 18th centuries, cherubic representations of fetus in transparent wombs greet bewildered readers who, like me, had never heard of "birth figures". Whiteley says that the illustrations were woefully inaccurate and conveyed baffling assumptions about female independence. Whiteley puts birth figures in the context of debates over reproductive rights by changing them to feminist iconography.

The original title of this article was "Reviews" in Scientific American.

The scientificamerican1222-74 was published in the journal.

World-changing science is what you'll discover. We have articles by more than 150 winners of the prize.

Subscribe Now!

Cookies are used to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and personalize content to provide social media features. Information about your use of our website is shared with our partners. Click on Cookie settings if you want to opt out of cookies.