Global markets have taken heart from the data indicating that inflation may have peaked, but economists warn against the return of the "transitory" inflation narrative.

October's U.S. consumer price index came in below expectations, as investors began to bet on an easing of the Fed's aggressive interest rate hikes.

Many economists don't think that a fundamental disinflationary trend will come from a decline in headline inflation rates.

The school of thought that projected rising inflation rates at the start of the year would be fleeting is what Paul Hollingsworth warned investors about on Monday.

The chairman of the Fed issued a mea culpa after he realized that the central bank had made a mistake.

Hollingsworth said that there are upside risks to the headline rate next year, including a possible recovery in China.

One of the key features of the global regime shift is greater volatility of inflation.

A combination of base effects and dynamics between supply and demand shift are expected to cause headline inflation rates to fall next year, according to the French bank.

According to Hollingsworth, this could revive the "transitory" narrative next year, or at least a risk that investors "extrapolate the inflationary trends that emerge next year as a sign that inflation is rapidly returning to the 'old' normal."

He suggested that the narratives could translate into official predictions from governments and central banks.

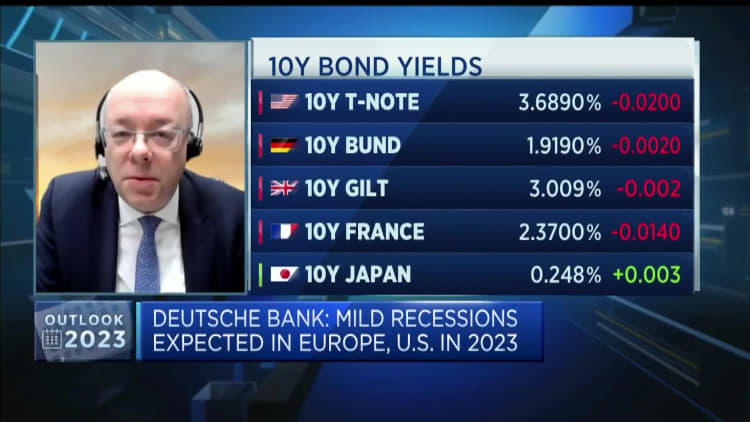

The bank was skeptical about a return to normal inflation levels. Christian Nolting told CNBC last week that the market's pricing for central bank cuts was premature.

There is a mild recession but from an inflation point of view we think there are second-round effects.

The seventies were similar to the time when the Western world was hit by an energy crisis, he said.

From our perspective, we think inflation is going to be lower next year, but also higher than previous years, so we will stay at higher levels, and from that perspective, I think central banks will stay put.

Some significant price increases during the Covid-19 pandemic were widely considered not to actually be inflation, but a result of relative shifts reflecting specific supply and demand imbalances, and the same is true in reverse, according to a new study.

Hollingsworth said that deflation in some areas of the economy should not be seen as an indicator of a return to the old inflation regime.

He suggested that companies may be slower to adjust prices downward than they were to increase them, because of the effect of surging costs on margins.

Services inflation is likely to be stickier because of wage pressures.

There has likely been a structural element to the historically tight labour markets in the U.K. and U.S.

The stock market in Hong Kong and the mainland rebounded on Tuesday after Chinese health authorities reported an increase in senior vaccine rates, which are seen as crucial to reopening the economy.

A gradual relaxation of China's zero- Covid policy could be inflationary for the rest of the world, as China has been contributing little to global supply constraints in recent months.

Hollingsworth said that a stronger recovery in Chinese demand is likely to put upward pressure on global demand for commodities and thus fuel inflationary pressures.

The war in Ukraine has accelerated the trends of decarbonization and deglobalization, which are likely to heighten medium-term inflationary pressures, he said.

The shift in the inflation regime is not just about where price increases settle, but also about the degree to which inflation will change over the next two years.

Inflation volatility is currently very high and we think it will fall. We don't expect it to return to the levels of moderation.