A streak of light over South Australia was seen by a constellation of US defense satellites.

An explosion equal to 220 tons of TNT was created by the impact. The bang was heard by detectors normally used to listen for low-frequency sounds from illegal nuclear tests.

There should be a patch of ground near Port Augusta covered in meteorites. How could we find them?

The Desert Fireball Network, which tracks incoming asteroids and meteorites, had a couple of ideas, including weather radar and drones.

The eyes are looking in space.

It is difficult to find meteorites. The Global Fireball Observatory only covers 1% of the planet.

The US satellite data published by NASA only picks up the largest fireballs. They don't always give an accurate estimate of the meteorite's trajectory.

You need help to find a meteorite from these data.

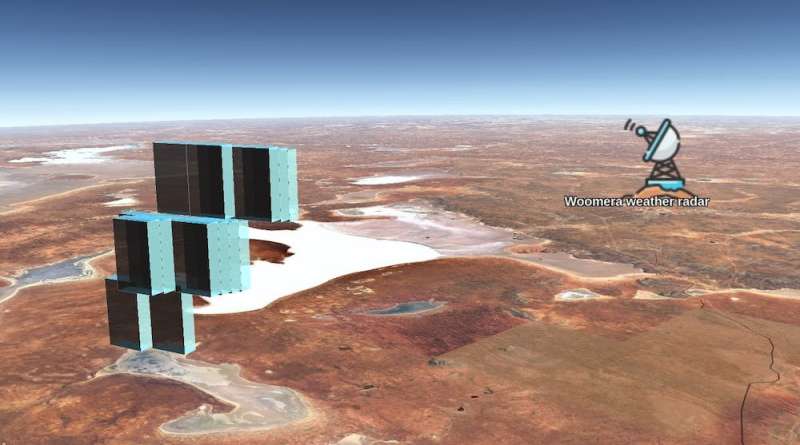

The weather radar.

The Bureau of Meteorology made its weather radar data available to the public. This was a chance to complete the puzzle.

I compared the records from the Desert Fireball Network and NASA with nearby weather radars. I looked for signs of falling meteorites on the radar.

The event was close to the radar station. The weather was clear and the radar record showed some small reflections.

I used the weather data to figure out how the wind would push the meteorites down to Earth.

The location of a rich haul of meteorites would be shown on a treasure map. I would send my team to the desert for two weeks if I got them wrong.

There is a search.

Andy Tomkins was given a treasure map by my colleague. He drove past the site on his way back from the expedition.

Andy was able to find the first meteorite in 10 minutes. His team found nine more in the next two hours.

My colleague in the US invented the technique of finding meteorites with weather radars. This is the first time it has been done outside of the US. The US has more powerful and dense tech than any other country.

There were a lot of meteorites. How would we locate them all?

The drones come in that location. Seamus Anderson developed a method to detect meteorites from drones.

We collected 44 meteorites that weighed in at over 4 kilogram. They form a field.

Strewn fields give us a lot of information about asteroids.

The energy of these things is similar to that of nuclear weapons. The asteroid that exploded over Chelyabinsk in Russia produced an explosion 30 times the size of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Predicting how the next big one will deposit its energy in our atmosphere is useful when it's about to hit.

Some asteroids are starting to be seen with better technology. When projects such as the Vera Rubin Observatory are up and running, we will see more.

The systems could give us as little as a few days' notice that an asteroid is headed for Earth. It's too late to try and distract it, but there's plenty of time for damage control.

Open data has a value.

The find was possible because of the free availability of crucial data.

Missile and rocket launches are likely to be detected by the US satellites. Someone must have figured out how to publish some of the satellite data without giving away too much about their capabilities, and then Lobbyed hard for the data to be released.

The find would not have been possible without the work of Joshua Soderholm at Australia's Bureau of Meteorology, who worked to make low-level weather radar data open for other uses. In order to make the radar data readily available and easy to use, Soderholm went to the trouble of making the data available at the bottom of scientific papers.

There are many fireballs to find. We're looking for a meteorite that was spotted in the sky over Canada last weekend.

Under a Creative Commons license, this article is re-posted. The original article is worth a read.