The nine months between conception and birth give human babies a chance to grow and develop.

It is not known how evolution came to grant humans such rapid growth.

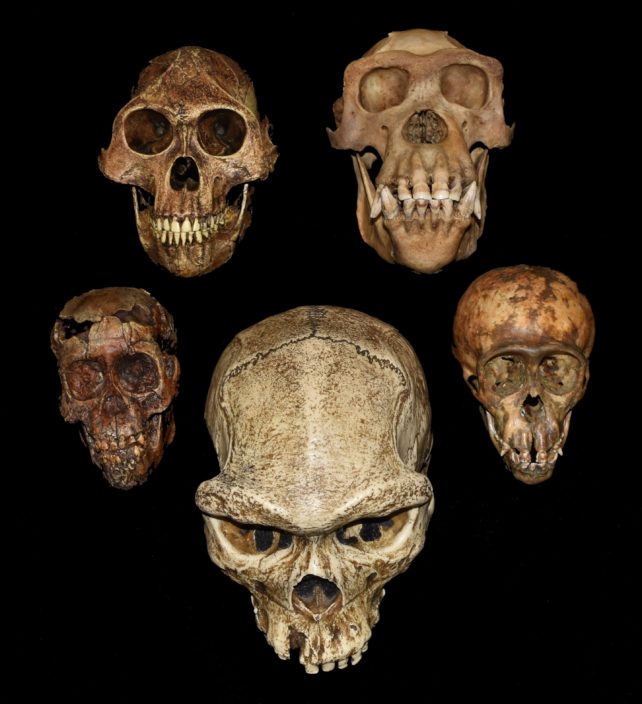

Researchers suspected teeth might hold some information on our ancestors' pregnancies because of how critical brain growth is to early human development.

The hardened exterior layers of the teeth are not developed until after the second trimester. Records of their life history can be retained from the beginning.

Leslea Hlusko from the Spanish National Research Center for Human Evolution says teeth are the most abundant parts of the fossil record.

The team's previous research in monkeys found a link between slower growth of an unborn animal and a lack of third molar development.

They found that all of the primate's growth rates, head sizes, and relative molar sizes were the same. They used this pattern to look at primate fossils dating from 6 million to 12,000 thousand years ago.

Fetal growth rates have increased over the last 6 million years. There is a theory that long human-like pregnancies evolved during the last few hundred thousand to million years.

The primate transition to walking on two legs in the Early Pliocene was similar to that of the monkeys and apes.

The evolution of Homo erectus in the Early Pleistocene resulted in a noticeable change in their body parts.

In their paper, the team states that there are independent lines of evidence that support human-like pregnancies and birth in the later Homo species.

The expansion of grassland and herbivore populations may have provided the Homo genus with the extra resources needed to fuel the increase in maternal investment.

It is possible that the evolution of group hunting, as well as the growing brain size of our ancestors, may have contributed to the advancement of tools that we have today.

The feedback loop may have allowed for the evolution of larger brains and increased cranial capacity in later Homo.

The research was published in a journal.