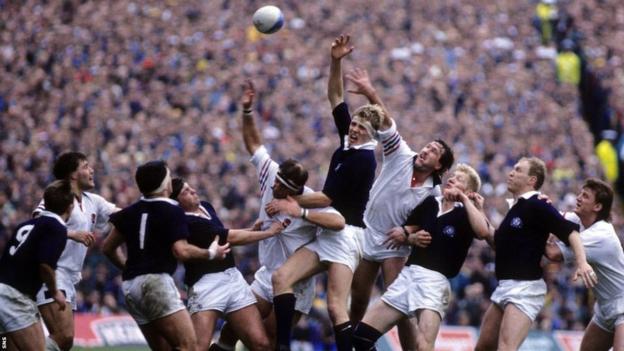

Bill McLaren once described Doddie as carrying a ball like a mad giraffe and the images of his playing years have a wonderful consistency. He is large and happy. A funny person.

He was on the rugby field, and all of those freeze-frames and video show it.

From Melrose, where he won a league title as a young man, he went on to win another. To Scotland for a decade and the Lions in South Africa, which was cut short by a horrible act of foul play by a local hatchet man.

He was six feet seven inches of joy.

There is a reluctance to refer to sports people by their first name or nickname because you don't want to appear familiar, but there are exceptions.

People who weren't familiar with him felt the same way. Those who were never in his company referred to him as Doddie.

Some people just have something. Doddie was a part of that group. The best in people came from him. He wanted his company to feel better about themselves and he wanted to make you happy.

There is a picture of a 20-year-old Doddie celebrating his league title with Melrose. Jim Telfer was the coach at the time. Telfer said the triumph with Melrose meant more to him than the Grand Slam with Scotland.

Doddie's smile was as wide as the Tweed on his face in the picture. The man was in his element. It was split between the amateur and professional eras, but he preferred the amateur one.

He was not a monkey. He didn't like training but he liked talking. Are you lifting a weight or a bar? There was nothing to make a decision on.

When the chips were down on the pitch and his mates needed him to go the extra mile, he once said that no bleep test, or any device to monitor the fitness of the first wave of professional players, could judge a man's personality. There was no way to measure a person's personality. He was one of the best.

Rugby was seen as a vehicle for making friends and memories by him. The man wanted to win. He wanted to have a laugh and no prouder Scotsman has worn the jersey or paraded the tartan with such gusto. He did what he was told to do.

His aura was never greater than when he used a wheelchair because of the effects of motor neurone disease. He was stronger when his body broke down than when he lost the ability to speak and could only use a voice app to communicate.

His determination to fight an illness without a cure was inspiring. He said the only drug he had was positive reinforcement. The millions of pounds he raised for research through his My Name'5 Doddie Foundation, the money donated to families who were suffering as a result, the lives he made better along the way. His legacy could go on for a long period of time.

He was told he wouldn't be able to walk within a year after he was diagnosed. For a start, he beat that prediction. A third of sufferers die within a year. He could see that one off as well. Within two years of being diagnosed, more than half of people pass away.

Doddie was still carrying the weight of personality three years after he was diagnosed. He joked that his trustees were the only ones upset about being three years in. They thought they were only signing up for a short period of time.

His attitude was based on reality. He had to "crack on" as he said. I have never considered why me. Let's get this sorted... it's similar to rugby. Do you fight or give up your jersey if you don't make the team?

He said that he is living the dream because he is having a living wake. Some people may have shed a tear at such bravery.

Five years after getting the news, he was still doing interviews, posing on his mobility scooter on his farm, like he was on a Harley Davidson. He said he's still smiling.

And continuing to campaign. He was critical of the government because they failed to deliver on their promises. He wanted to know if medical experts were moving fast enough to trial new drugs.

His movement was compromised, but he never lost his passion. Other people with MND, with no influence or profile, must have seen him as their champion, fighting the good fight in pursuit of something that will save their lives.

While knowing that his life was ending, he did it with a sense of humor and wisdom.

When his sons wheeled him to the side of the Murrayfield pitch before the All Blacks game earlier this month, the atmosphere inside the stadium was an amazing amalgam of joy and sadness. Since the diagnosis, more than six years have passed.

He had won 33 of his 61 caps. He made his debut there and scored his first international try there.

The last one, in the chair with his sons by his side, two sets of players applauding him and the love of 67,000 people cheering him on was the most memorable appearance of all, according to many.

It must have been difficult for him to be there, but not many of us have encountered a character like him before. It was missed. Never forgotten.