There are thousands of languages in the world. The linguistic diversity is passed on from generation to generation. Charles Darwin thought that language and genes had evolved in parallel over the course of thousands of years.

This question has been examined at a global level by an interdisciplinary team at the University of Zurich. A global database linking linguistic and genetic data entitled GeLaTo (Genes and Languages Together) contains genetic information from 4,000 individuals speaking 295 languages. The work is in a journal.

Language shifts can be seen in one in five genes.

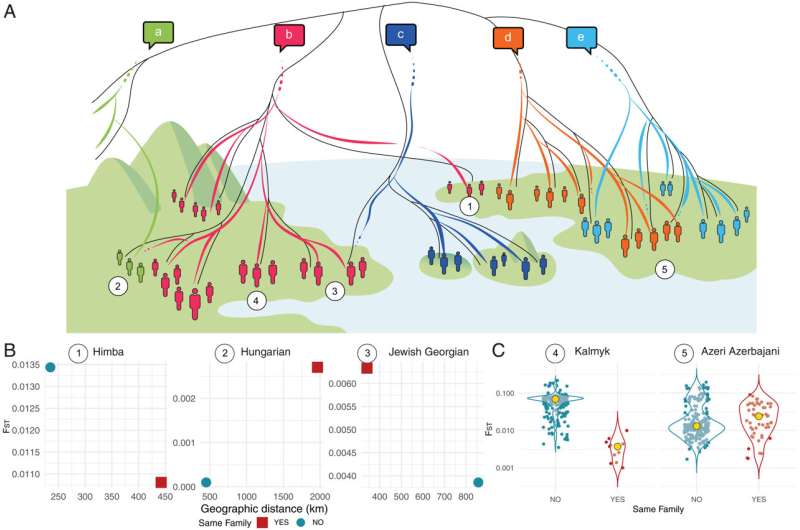

The researchers looked at the extent to which the histories of populations were related. People who speak related languages tend to be related to one another. The study focused on cases where the biological and linguistic patterns differed and investigated how often and where these mismatches occur.

Every fifth gene-language relation is a mismatch, according to the researchers. Insights into the history of human evolution can be provided by these mismatches. The director of the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) Evolving Language, who co-supervised the study, says that "once we know where such language shifts happened, we can better reconstruct how languages and populations spread across the globe."

It's time to switch to the local jargon.

Populations shift to the language of a neighboring population that is different from them. Some people on the tropical eastern slopes of the Andes speak a Quechua language that is typically spoken by groups with different genetic profiles. A group of people who are genetically related to the Bantu are communicating in a language other than English. Some hunter-gatherers in Central Africa don't have a strong genetic relation to the Bantu populations.

Migrants can pick up the local language of their new home. The Jewish population in Georgia uses a South Caucasian language while the Cochin Jews in India use a Dravidian language. While the Maltese are related to the people of Sicily, they speak an Afroasiatic language that is influenced by many Turkish and European languages.

Preserving their culture.

"For practical reasons, it appears that giving up your language isn't that difficult," says the last author. It's more rare for people to retain their original linguistic identity even though they're genetically different from one another. Hungarians are genetically similar to their neighbors, but their language is related to languages spoken in Siberia.

It makes Hungarian speakers stand out from the rest of Europe and parts of Asia where most people speak other languages. It has been extensively studied and scores high in terms of genetic and linguistic congruence. It's important to include genetic and linguistic data from populations all over the world to understand language evolution.

There is an analysis of matches and mismatches between human genetic and linguistic histories. 10.1073/pnas.

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences