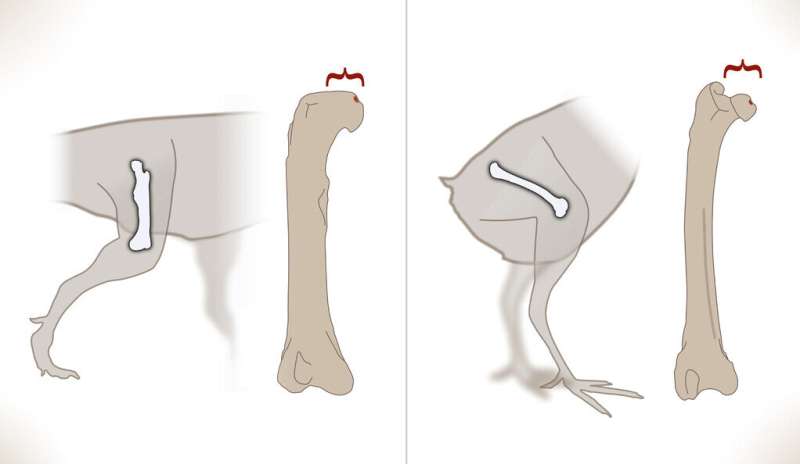

Dinosaurs and birds wouldn't have been able to stand on their own two feet without their upper thigh bones being altered. A new study shows the evolutionary course of these alterations.

The findings resolve a longstanding question about dinosaur evolution and offer a prime example of how new physical features can pop up briefly during embryonic development and then move on to older, known features in adults.

A research team led by Yale's Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar and Shiro Egawa looked at the evolution of thefemoral head in a wide range of dinosaurs, early reptiles and birds. The study appeared in a journal.

The team included researchers from the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry in Japan and the American Museum of Natural History.

The way in which the femoral head developed was figured out by the associate professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Yale. Bipedal locomotion can be done with inward-turned femoral heads.

There had been differing theories about how dinosaur femoral heads developed. The theory held that the femoral head simply grew an attachment that rearranged the legs. Over time, the femoral head twisted inward.

There is evidence for both the twisting theory and the in-growth theory.

The researchers studied femoral head development in a variety of fossils and animal embryo. The lab at Yale is well-known for its innovative use ofCT scanning and microscopes to create 3D images of fossils.

Evidence for both theories comes together.

Even though the feature remained constant in adults, the development of the major feature changed completely. This sort of hidden shift in development may be more common than we think, and it should serve to caution against the idea that features which develop differently must have evolved separately.

The study's first author and co-corresponding author is Shiro Egawa, a former associate in Bhullar's lab.

Two former Yale researchers, Joo Botelho and Daniel Smith-Paredes, co-authored the paper.

The dinosaurian femoral head experienced a morphogenetic shift from torsion to growth along the bird's stem. There is a book titled "PukiWiki" which can be found at 10.1098/rspb. 2022.0740.

Journal information: Proceedings of the Royal Society B