A new study has found that toxes released by a type of bacterium that cause the disease hijack cell processes and force important proteins to assemble into "roads to nowhere."

Actins, which are highly abundant and have multiple roles, help every cell unite its contents, maintain its shape, divide and migrate. Actins are used to do certain work in cells.

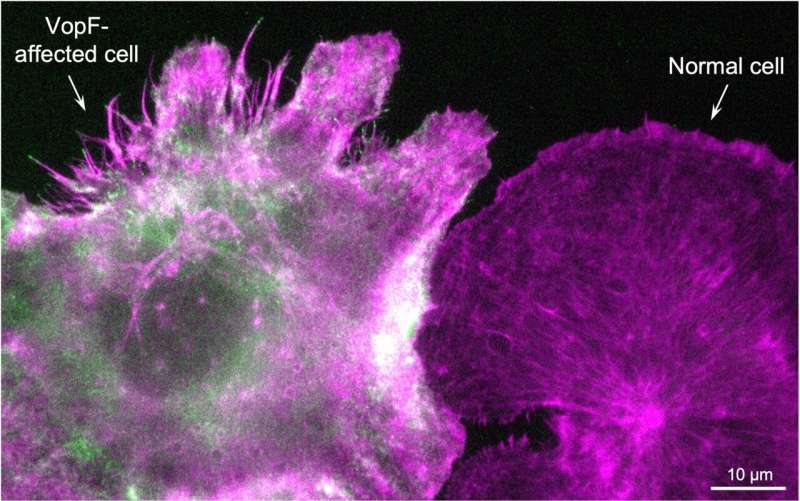

Researchers found that two toxins produced by the vibrio genera ofbacteria cause actins to join together at the wrong location inside cells and headed in the wrong direction

"Growing in the wrong direction is a totally new function that was not previously known and was not thought to be possible for actin filaments inside the cell," said senior author Dmitri Kudryashov. Cell resources are wasted and cannot be used to satisfy the cell's basic needs because a large portion of actin in the cell is consumed in formation of the "highways" where they are not needed.

The research is in a journal.

The VopF and VopL are produced by two strains of vibriobacteria, which can make people sick if they eat raw oysters.

The research team zeroed in on describing the unexpected cellular activities rather than thinking about how the hijacking relates tobacterial infections.

Elena Kudryashova, a research scientist in chemistry and biochemistry at Ohio State, is one of the authors.

She said that knowing your enemy helps you fight your opponent. It was possible for actin to behave in such a way inside the cell that raises new questions about whether this function might actually be needed, or could come about in some other way.

Actins have been known to assemble each strand in one way, starting from the point of the structure and ending at the barbed end. Because they are limited in number, the actins disassemble as needed from the pointed end and are recycled to maintain directional activity towards the barbed end.

When the VopF and VopL toxins enter a cell, they attract actin molecule to start a newfilament and cause it to assemble in this spot, which leads them to go in a different direction than usual.

The actin interference was observed through the use of live cells. They don't know all the consequences of this hijacking activity, but the researchers said the results could include seepage of nutrients through damaged intestinal walls.

Killing cells is not always necessary.

The scientists want to know if other molecules can force actins to assemble "roads to nowhere" and if that strange formation is a beneficial mechanism under a different set of circumstances.

It's possible that our own cells are doing this, but we don't know because actin has so many functions.

The Ohio State team collaborated with several other authors.

Elena Kudryashova et al, Pointed-end processive elongation of actin filaments by VopF and VopL, was published in the journal Science Advances. There is a book titled "Sci Adv.adc9239."

Journal information: Science Advances