Models suggest that the US could be headed toward 150,000 COVID-19 cases by the end of the month, with only 45,000 ICU hospital beds nationwide. But there are some things we can do to help.

Posted on March 12, 2020, at 7:20 p.m. ET

WASHINGTON - The new front lines of the coronavirus pandemic are emergency rooms, where hospitals are desperately readying for repeats of scenes of overwhelmed wards in Wuhan, China, Milan, and Tehran, as the outbreak crests this month in the USA.

Hospital groups on Wednesday appealed to President Trump to declare the COVID-19 outbreak a national disaster or emergency, a declaration that would allow hospitals to add more hospital beds and enable out-of-state doctors to assist in the event of a crisis.

"We're going to see a lot more cases but I think we are taking the big steps to limit the dangers to patients," the American Hospital Association's Nancy Foster told BuzzFeed News. "I'm not a person who does modeling, but I'm optimistic we have taken all the steps."

But modeling studies, as well as the current capacity of beds and equipment at US hospitals, point to grim possibilities for the US hospital system.

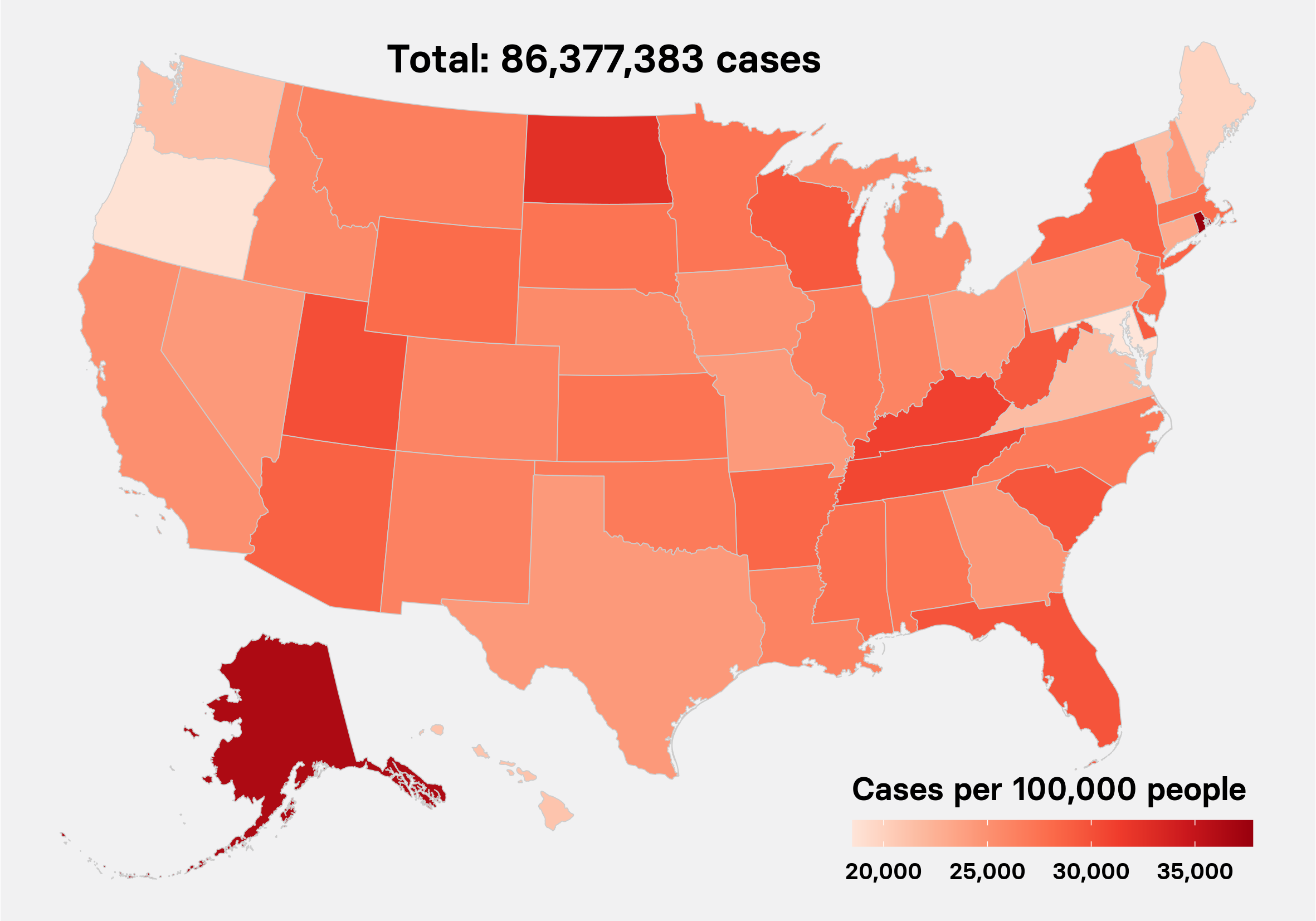

First, the numbers to date: More than 1,300 US cases were reported as of Thursday, with beachhead community outbreaks in Washington state, California, and New York. Cities like Atlanta, Miami, Boston, and Denver are reporting dozens of cases each. Total case numbers have grown at a rough average rate of 30% a day in the US since the last week of February.

At that rate, the US will have more than 8,000 cases by next week, 40,000 cases in two weeks, and nearly 150,000 cases by the end of the month. Around 5% of those cases might be critical ones, leaving 7,500 Americans with life-threatening cases of COVID-19. Although the nationwide "social distancing" moves of the last two days - closing schools, theaters, and professional sports events - might cut into this growth, they didn't help right away in China when even more draconian measures started in late January, noted a preliminary Harvard and Johns Hopkins analysis of intensive care bed needs in a COVID-19 outbreak.

By the peak of the outbreak last month in Wuhan, nearly 20,000 patients were hospitalized simultaneously, with 10,000 in severe or critical condition. If a Wuhan-like outbreak were to take place in a US city, even with people isolating themselves, the study authors concluded, "hospitalization and ICU (intensive care unit) needs from COVID-19 patients alone may exceed current capacity."

Another model from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health suggests that a "moderate" scenario for the coronavirus pandemic, akin to a 1968 flu pandemic, could lead to 1 million people in the US requiring hospitalization this year. A "severe" outbreak would hospitalize 9.6 million people.

Social distancing will be a necessity to prevent more severe scenarios.

"A little more alarm is needed," said epidemiologist Caroline Buckee of Harvard's T.H. Chan School of Public Health. "We need people to start taking personal responsibility for social distancing right away."

"Staff and supplies are the biggest concern," Tim Pfarr of the Washington State Hospital Association told BuzzFeed News. Washington is now facing the largest outbreak in the US, with 373 cases and 30 deaths, largely among residents of a nursing home in Kirkland, Washington. Hospitals in the state are modeling their coronavirus response after a 2017 Amtrak derailment that killed three people and sent 70 to the hospital, he said, expressing confidence in their readiness for a bigger outbreak.

Asked about whether the hospitals would have the capacity to accommodate the hundreds to thousands of undetected cases some models suggest are currently in the state, he said, "we have had a lot of experience with pandemics before, like H1N1, so we are building off that experience."

There are around 6,000 hospitals nationwide, with more than 900,000 hospital beds outside of the intensive care unit (ICU), according to the AHA. That sounds like a lot, but remember: It is fewer than the millions of hospitalized cases that could occur in a pandemic resembling the 1968 flu. And people will still get the flu, have car wrecks, and deliver babies, needing some large portion of those beds.

That same "moderate" 1968 scenario would also put 200,000 patients into ICUs, while a "severe" outbreak would require 2.9 million people receive ICU care.

"As a comparison, there are about 46,500 medical ICU beds in the United States and perhaps an equal number of other ICU beds that could be used in a crisis," the Johns Hopkins study authors, Eric Toner and Richard Waldhorn, wrote. "Even spread out over several months, the mismatch between demand and resources is clear."

Since the most severe symptom associated with COVID-19 is the respiratory failure associated with severe pneumonia, the biggest worry aside from capacity at hospitals is about the number of ventilators, as well as the specialists who can staff them. There are an estimated 150,000 respiratory therapists in the US, and about 160,000 machines. In Washington state, a request has been made to a national stockpile of medical equipment to release more ventilators, said Pfarr. The stockpile maintains another 10,000 ventilators, which come in three varieties. A 2018 analysis reported most should function well out of the box, aside from one model that only lasted 58% as long as expected.

The shortfall between the numbers of beds, ventilators, and staff against projected numbers of cases - pitting the hundreds of thousands against the millions - explains the drumbeat of calls to help "flatten the curve" of the outbreak. It's a simple idea: A tidal wave of sudden cases in just a few weeks will swamp emergency rooms, but the same number of cases spread over months will test the surge capacity of hospitals without overwhelming them. Two hundred thousand ICU cases in the "moderate" pandemic scenario hitting hospitals in the next three months would overwhelm the 46,500 ICU beds we might have available. But spread over a year, those 200,000 cases would be a difficult, but possible, strain for our hospitals to handle.

This #FlattenTheCurve graph surged to prominence this week. But it didn't say why it is so bad when medical treatment capacity is overwhelmed -> mortality rate rises. So, here is a small animation that shows the value of early containment and double dividend of delay. #Covid19

"It is impossible to predict the impact COVID-19 will have on our nation's staffing of respiratory therapists or for how long it might last," Thomas Kallstrom of the American Association for Respiratory Care told BuzzFeed News. "Should the need arise, hospitals would be wise to consider reaching out to recently retired respiratory therapists as a backup and, if necessary, consider enlisting students."

A Wuhan-style outbreak in a US city would mean 2.1 to 4 critically ill patients per 10,000 people, depending on factors like the average age and high blood pressure status of its residents. US ICU beds average about 2.8 per 10,000 adults. Cities like Detroit, Memphis, and Louisville look potentially at high risk of critical care shortfalls by that measure, according to the preliminary ICU analysis from Harvard and Johns Hopkins.

The consequences of not flattening the curve are horrible, a switch from treating patients on a "sickest first" basis to "most likely to recover" as a basis for allocating ventilators, described in a 2011 CDC pandemic ethics publication. "After a public health emergency is declared, rules that favor the overall benefit to the population and society may have to be considered," the CDC wrote.

More than 3,000 people have died from COVID-19 in Hubei Province, China, home to Wuhan, since the start of the year.

Some hospitals have started adding parking lot tents for screening for coronavirus to increase capacity. The tents, which the American Hospital Association describes as standard parts of emergency planning, also help keep patients with dangerous illnesses separate from others, especially high-risk groups like diabetics or people with lung illnesses.

On the plus side for hospitals, AHA's Foster added, the coronavirus appears largely transmitted through contact with droplets from coughs and sneezes, but not through the air like measles. That means that while staff have to wear protective gowns, gloves, and masks - another area of reported shortages - at least they won't be required to prepare costly negative pressure hospital suites to handle patients, like in the 2014 Ebola outbreak. CDC guidelines do call for these rooms for people undergoing procedures that will lead to a lot of coughing by patients.

One approach to sparing hospital staff is the advent of drive-through testing for coronavirus, seen in Seattle, Denver, and Hartford, Connecticut. The "fast-food" approach's goal is to minimize the exposure of staff to sick patients, limit the amount of protective gear exposed, and get as many people tested as possible.

Telemedicine approaches to treating patients with COVID-19 are also about to get a tryout, said Edward O'Bryan of the Medical University of South Carolina. Everyone in his state is now able to access an online portal to see about 90 specialists through phone, video, or a chatline ahead of going to the doctor's office or an emergency room with symptoms, helping take pressure off those points.

"We're staffing up," said O'Bryan, who added that he has been preparing the telemedicine portal in preparation for an outbreak like this for five years. "Luckily in South Carolina, we have an emergency about once a year - it's called a hurricane - so we have had a lot of reasons to try to get ready."

Looming over preparations for the US outbreak is the uncertainty of the extent of the disease, driven by a shortfall in testing tied to a botched CDC public health lab test, strict and sometimes contradictory criteria for testing, and federal limits on academic and private lab tests removed only in the last two weeks. The result has been a country waking up daily to hidden blooms of cases suddenly revealed by fresh testing. With the private labs used by most doctors to perform lab tests only now entering the arena, say experts, there are still more surprises to come.

"Until we have more testing, we are really working in the dark," said Harvard's Buckee.

Former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb testified to Congress on Thursday that labs in the United States currently only have the capacity to process lab tests of about 17,000 patients a day. That's fewer than the number of cases the US should have in the next 10 days under current rates of increase.

Also testifying to Congress on Thursday, Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, added that the testing in the US, "is a failing. Let's admit it."

Until widespread testing is put in place and the full COVID-19 picture emerges, confusion and uncertainty will surround the outbreak, adding to the mounting fears that always accompany epidemics.

"There are four cases in Ohio, three of which are in my county," Henry Bloom, a family practice doctor in Shaker Heights, Ohio, told BuzzFeed News. "I still can't get N95 masks. I still also worry that we should be testing for anyone with any respiratory symptoms, because people often don't fit with the official description."

"I have hotline numbers, but don't know if they work, and don't want to clog them to see," Bloom added. "Does that sound like [we're] ready, to you?"