In the summer of 2020, months after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global epidemic, Samira Mubareka and her colleagues began testing wildlife for the new coronaviruses.

Mubareka is an associate professor in the department of laboratory medicine and pathobiology at the University of Toronto. Reports of zoo and companion animals getting infections were reported.

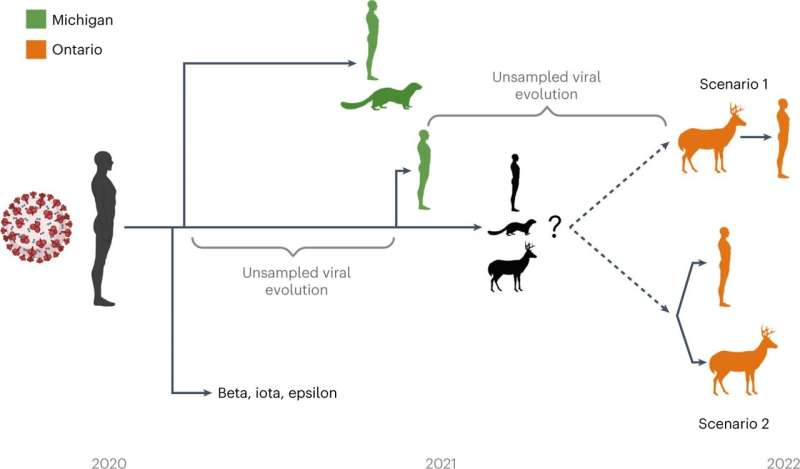

It's an important aspect of the response to the disease. Pathogens that can move between animals and humans are particularly worrying. When introduced into new animal hosts, the pathogen can create a new disease that can be passed on to humans and possibly cause them to get it. It can be more difficult to detect and treat the new variant in humans.

Mubareka joined a working group with researchers from universities, hospitals and leading provincial and federal government agencies.

The team did not find any evidence of the disease in the wildlife they studied.

Mubareka and her colleagues focused their efforts on the white-tailed deer in Ontario and Quebec after they were exposed to the disease in the US.

They were able to find what they were looking for. In the first detection of the disease in Canadian wildlife, the group was able to confirm the presence of the disease in three deer in southern Quebec.

The first evidence of deer-to-human transmission was found in a new study by Mubareka and colleagues.

The new variant is a descendant of an older, parental B.1 virus and has a lot of changes compared to the previous strain. The currently dominant omicron BA.5 variant has 105 mutations, compared to the alpha, alpha and delta variant's 24 and 31 mutations.

Mubareka, who is a member of the steering committee of the Emerging and Pandemic Infections Consortium at the University of Toronto, said that he was not expecting to find a highly diverging virus.

Blood samples from people who had recovered from COVID-19 or received at least two or three doses of the vaccine were able to identify the new variant even though it had a few quirks. This suggests that the genetic changes in this variant aren't helping it to evade the immune system.

Humans who had tested positive for the disease in Ontario around that time were compared to the new variant's sequence. One sequence that closely matched the variant from white-tailed deer was found to be related to the virus.

There are a lot of public interactions with wild deer and captive deer. According to Mubareka, deer are important from both a food security and cultural perspective.

The Public Health Agency of Canada made new recommendations to reduce risk for hunters, trappers and other people who work with wildlife. When handling a carcass, processing carcasses outdoors or in a well-ventilated area, and cooking meat to an internal temperature of 74 C to kill any parasites, it's important to wear protective equipment.

When a new virus is found, you want to understand how dangerous it is. The follow-up work will focus on what this virus does in humans and animals.

She is working with two other people to study how the virus behaves in lung organoids and nasalcells grown in the lab. She is working with others to understand how the deer's immune system evolved to support the spread of the disease.

To address the possibility of this new variant spreading from deer to other wildlife species, Mubareka is once again teaming up with partners at the provincial and federal level.

Collaboration is important in order to understand what this virus is doing in animal populations and how it could affect human health.

In white-tailed deer with deer-to-human transmission, a variant of the SARS- CoV-2 is emerging. The DOI is 10.1038/s41564-022-097-1

Journal information: Nature Microbiology