The Hebrew University, Bar-Ilan University Tel Aviv University, and the Natural History Museum in London collaborated with other institutions to analyze the remains of a huge fish.

An analysis of the remains of a fish found at an archaeological site in Israel shows that it was cooked around 780,000 years ago. The ability to process food by controlling the temperature at which it is heated is known as cooking.

Cooking dates to around 170,000 years ago have been known. The question of when early man began using fire to cook food has been debated for over a century. The findings were published in nature ecology and evolution.

Professor Naama Goren-Inbar, director of the excavation, and Dr. Irit Zohar, a researcher at TAU's Steinhardt Museum of Natural History were part of the study. Dr. Guy Sisma was part of the research team.

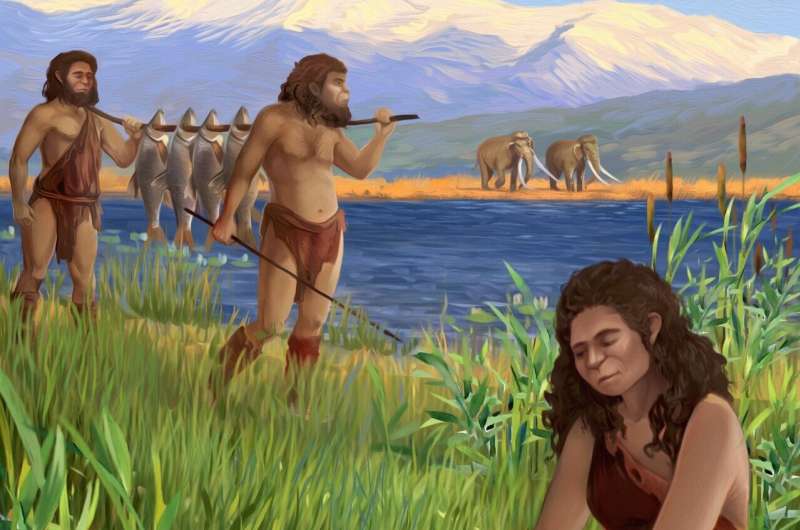

The study shows the importance of fish in the life of prehistoric humans. We were able to reconstruct the fish population of the ancient Hula Lake using the fish remains found at Gesher Benot Ya'aqob.

The barbs were up to 2 meters in length. The large amount of fish remains found at the site proves their frequent consumption by early humans. The importance of freshwater habitats and the fish they contained for the sustenance of prehistoric man, as well as their understanding of the benefits of cooking fish before eating it, are shown in the new findings.

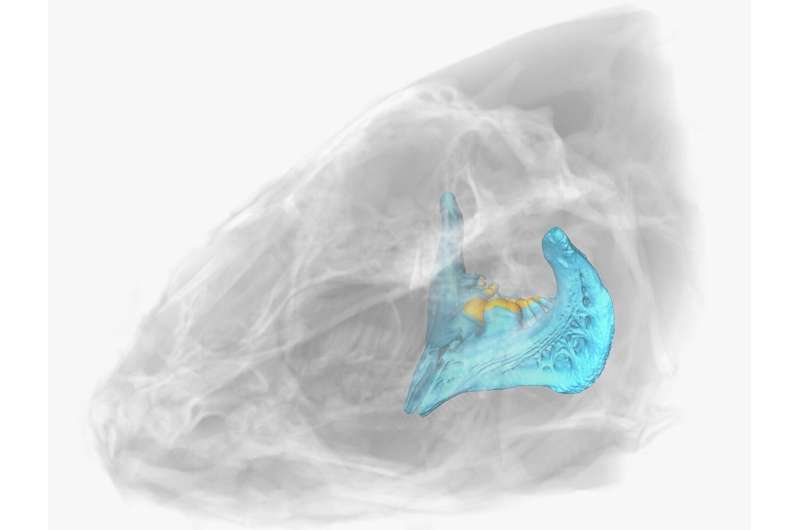

The researchers focused on the pharyngeal teeth, which are used to grind up fish food. There were a lot of teeth found at the site.

Until now, evidence of the use of fire for cooking had been limited to sites that came into use much later than the GBY site, and most of them are associated with the emergence of our own species.

Prof. Goren-Inbar said that the cooking of fish is visible over a long period of time at the site. This discovery relates to the high cognitive capabilities of the hunter-gatherers who were active in the Hula Valley region.

The groups were familiar with the environment and had many resources to offer. They had a lot of knowledge of the life cycles of plants and animals. Gaining the skill required to cook food marks a significant evolutionary advancement, as it provided an additional means for using available food resources. It is1-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-6556 is1-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-65561-6556

The transition from eating raw food to eating cooked food had dramatic implications for human development. The bodily energy required to break down and digest food can be reduced by eating cooked food. Changes in the human jaw and skull are caused by it.

Humans were free to develop new social and behavioral systems because of the change. A central catalyst for the development of the human brain is thought to be provided by eating fish.

According to them, eating fish made us humans. It's well known that the contents of fish flesh contribute to brain development.

According to the research team, the location of freshwater areas, some of them in areas that have dried up and become arid deserts, determined the route of the migration of early man from Africa to the Levant and beyond. The habitats provided drinking water and attracted animals to the area, so catching fish in shallow water is a relatively easy task with a high nutrition reward.

The first step on the way out of Africa was the exploitation of fish in freshwater habitats, according to the team. The revolution in the diet of the early man was caused by cooking fish, which is an important foundation for understanding the relationship between man, the environment, climate, and migration.

Evidence of the use of fire at the site was the first to be identified by a BIU professor. She said that the use of fire characterizes the entire continuum of settlement at the site. The spatial organization of the site was affected by this. The research of fire at the site showed that the use of fire began hundreds of thousands of years ago.

According to Goren-Inbar, the archaeological site of GBY shows a continuum of settlements by hunter-gatherers on the shores of the ancient Hula Lake which lasted tens of thousands of years.

Goren-Inbar explained that the groups used the resources of the ancient Hula Valley and left behind a long settlement continuum. The material culture of these ancient hominins, including flint, basalt, and limestone tools, as well as their food sources, which were characterized by a rich diversity of plant species from the lake and its shores, have been uncovered.

In this study, we used geochemical methods to identify changes in the size of the tooth crystals, as a result of exposure to different cooking temperatures. It's easy to see the dramatic change in the size of the crystals when they're burned by fire, but it's harder to see the changes caused by cooking at high temperatures.

We were able to identify the changes caused by cooking at a low temperature. We don't know how the fish were cooked but we do know that they were not thrown into a fire as waste or as material for burning.

The Israel Oceanographic and limnological Research Institute and Prof. Thomas Ttken of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz were part of the research group.

The study of isotopes allowed us to determine that the fish were not a seasonal economic resource but were caught and eaten all the time. The need for seasonal migration was reduced by the availability of fish.

There is evidence for the cooking of fish 780,000 years ago. The article can be found at www.nature.com/articles/s415522-01910-z.

Journal information: Nature Ecology & Evolution