Scientists have been able to find out what the first animals to make skeletons looked like thanks to a well-preserved collection of fossils. The results have been published in a journal.

In a geological blink of an eye, the first animals to build skeletons appeared in the fossil record around 500 million years ago. Many of the early fossils are simple hollow tubes. The skeletons lack the soft parts needed to be identified as belonging to major groups of animals that are still alive today.

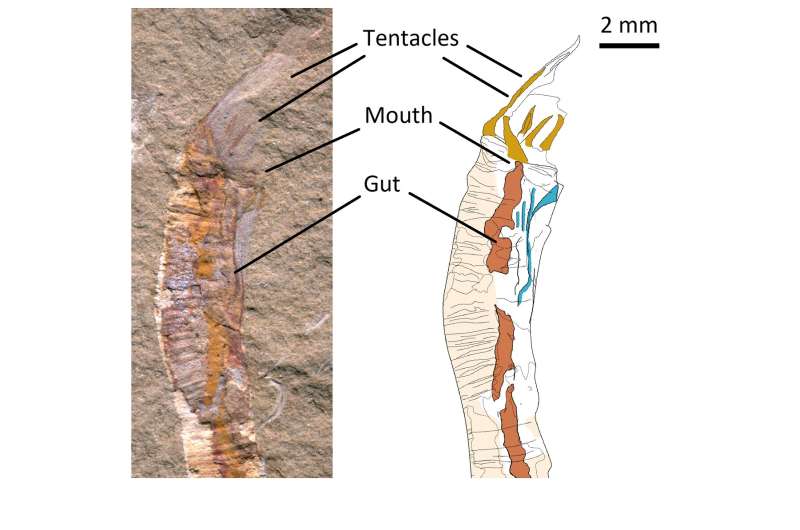

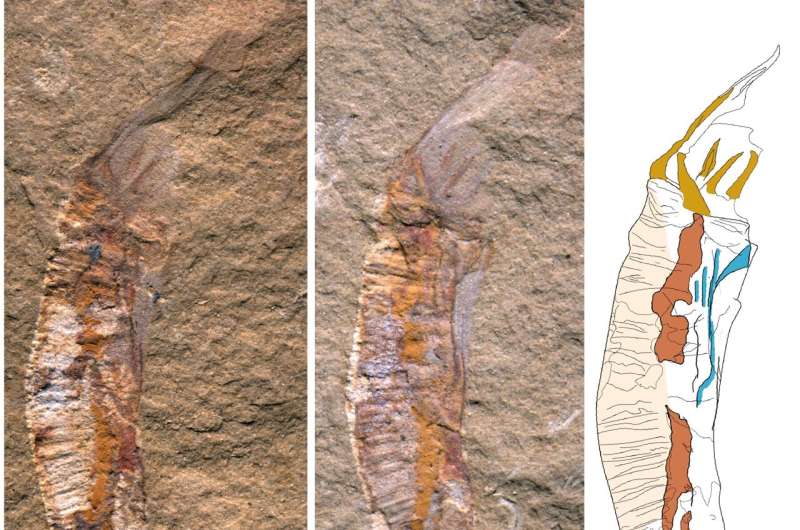

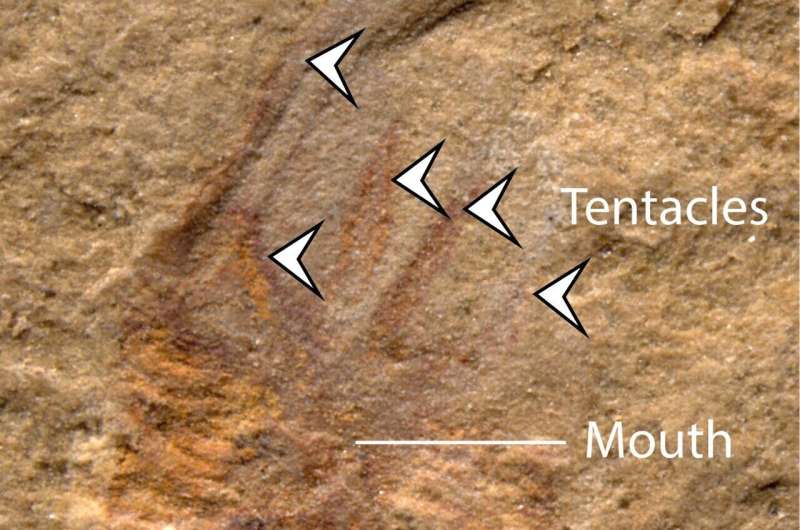

Gangtoucunia aspera is one of the four fossils included in the new collection. The mouth of this species was covered with a ring of smooth, unbranched tentacles. These are likely to have been used to sting and capture prey. Gangtoucunia had a blind-ended gut that was partitioned into internal cavities to fill the tube.

These features are rare in the fossil record and only found in modern jellyfish, anemones and their close relatives. The study shows that the simple animals were the first to build hard skeletons.

Gangtoucunia would have looked like a modern scyphozoanJellyfish polyps with a hard tubular structure anchored to the underlying surface. The mouth could have been pulled inside the tube to avoid being eaten by animals. The tube of Gangtoucunia was made of a mineral that makes up our own teeth and bones. Over time, the use of this material to build skeletons has become more rare.

This really is a one-in-million discovery according to theCorresponding Author Dr. Until now, these tubes have been seen as problematic fossils because we had no way of distinguishing them. A key piece of the evolutionary puzzle has been put firmly in place thanks to the new specimen.

The new fossils show that Gangtoucunia was not related to annelid worms as had been thought. Gangtoucunia's body had a smooth exterior and a gut partitioned longitudinally, which is different from annelid's bodies that have a split into two parts.

The site where the fossil was found is in the eastern part of the country. The presence ofbacteria that degrade soft tissues in fossils is limited by the lack of oxygen in the air.

I was surprised and confused when I found the pink soft tissue on the Gangtoucunia tube, the first time I saw it. The discovery of three more Gangtoucunias with soft tissue preservation made me rethink the affinity of the plant. The soft tissue of Gangtoucunia shows that it isn't a worm, but a coral, and that it is a cnidarian.

This doesn't rule out the possibility that other early tube- fossil species looked different, despite the fact that Gangtoucunia was a primitive jellyfish. The research team has previously found well-preserved tube fossils that are related to arthropods.

Xiaoya Ma, a co-corresponding author, said that a tubicolous mode of life may have become more common in the early Cambrian. The study shows that preservation of soft tissue is important for understanding ancient animals.

The paper will be published in the Royal Society B in November.

An affinity for a Cambrian phosphatic tubicolous is revealed by exceptional soft tissue preservation. Royalsocietypublishing.org/doi...

Journal information: Proceedings of the Royal Society B