The plan to harvest solar energy from space and beam it down to Earth is too good to be true.

According to Martin Soltau, the co-chairman of the Space Energy Initiative, it could happen as soon as 2035.

SEI is working on a project that will put a constellation of very large satellites in a high Earth circle.

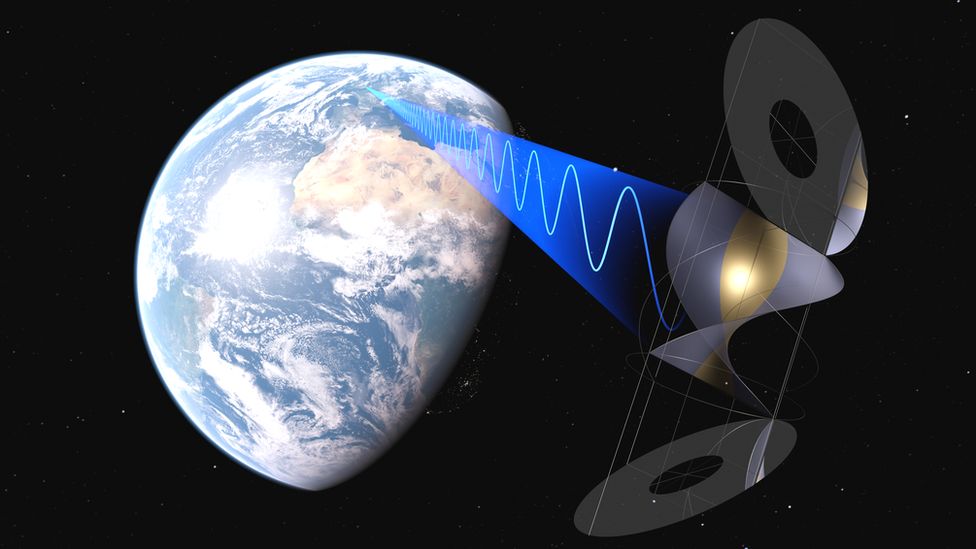

The satellites would harvest the sun's energy and send it back to Earth.

The potential is very large.

It could provide all of the world's energy in the future.

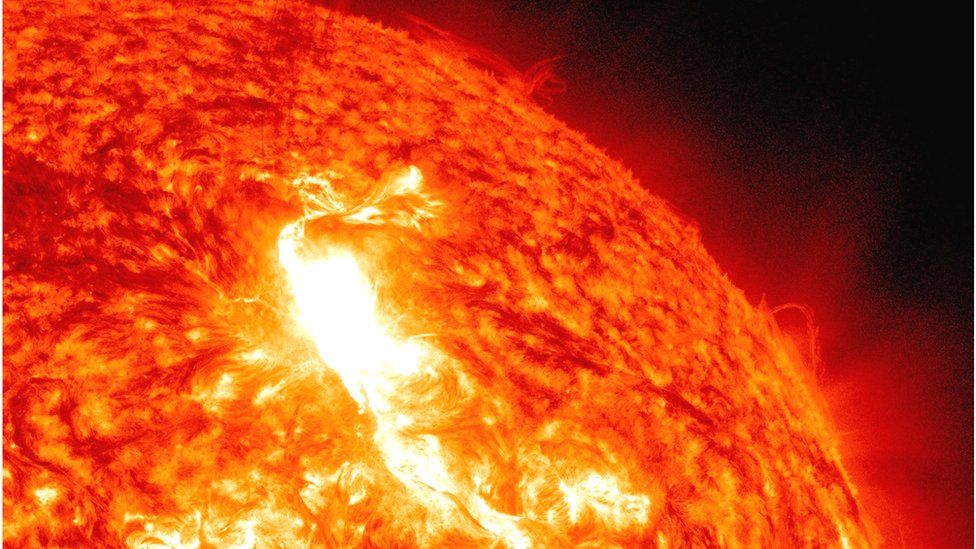

The Sun's supply of energy is vast and there's enough room for the solar power satellites in the space station. According to Mr Soltau, a narrow strip around the Earth's equator receives more energy per year than all of humankind will use in the next 40 years.

The UK government funded space-based solar power projects after an engineering study concluded the technology was feasible.

SEI is hoping to make a lot of money.

Its satellites would be made up of hundreds of thousands of small, identical modules produced in factories on Earth and assembled in space by autonomously-guided robots.

The solar energy collected by the satellites would be used to convert the radio waves into electricity.

The power output of each satellite is comparable to a nuclear power station.

On Earth, the sun's rays are diffuse by the atmosphere, but in space they come directly from the sun.

A space-based solar panel can collect more energy than a smaller panel on Earth.

Other similar projects are being developed.

In the US, the Air Force Research Laboratory is working on some of the critical technologies needed for such a system.

Improving solar cell efficiency, solar-to-radio Frequency conversion and beam forming, as well as reducing the large temperature fluctuations on spacecraft components are some of the things that are included.

The team was able to demonstrate new components for a sandwich tile, which converts solar energy into radio waves.

The microwave beams have been shown to be safe and effective for both humans and animals.

"The beam is microwave, so it's just like the wi-fi that we have all the time, and it's low-intensity, at about a quarter of the intensity of the midday Sun," said Mr Soltau.

If you were on the equator, you would get about 1,000W per square metres, and this is about 25% of that. It is safe in that regard.

Many of the biggest hurdles have been solved.

"My personal take on this is that we like to think the technology is there, but it's not quite ready yet for us to embark on a project of such complexity," says Dr.

She points out that launching a large number of solar panels into space will cost a lot and will generate a lot of carbon dioxide.

There is reason for hope. According to an analysis done by the University of Strathclyde, the carbon footprint of the project could be as little as half that of the sun, at about 24g of CO2 per kilowatt-hour.

The economic case is improving all the time.

The cost of launch has fallen by 90 percent and this has changed the economics.

There have been advances in the design of solar power satellites, so that they are more modular, which provides resilience and reduces production costs. We've got real advances in robot and system technology.

SEI is trying to get private investment for some of the technologies involved. The proposed timelines may be overoptimistic.

With significant investment and focused effort into this area, there's no reason why we can't have the system up and running as smaller pilot projects in the future.

It would take a long time for something on a large scale to be done.