A new research project analyzed the evolution of the placental mammal skull using 3D scans of 322 specimen housed in more than 20 international museum collections and created a new model of how mammals diversified based on the emerging patterns.

The team of researchers led by Prof. Anjali Goswami at the Natural History Museum have gained a unique look across time and taxa to trace the adaptive radiation which fills

The critical period after the last mass extinction 66 million years ago has shaped the evolution of our species.

The age of mammals has arrived.

The earliest mammals were limited in their diversity by the fact that they were smaller than a small dog. Within a few 100,000 years after the extinction of the dinosaurs there was an explosion of diversity among mammals, with the earliest ancestors of today's living groups appearing.

The pace of evolution slows down after the initial burst of mammal diversity. The impacts get smaller and smaller through the years, and never match the speed of the first peak. Climate change and the global cooling through the Cenozoic era are believed to be the cause of the later bursts.

The study shows that the skull shapes of most mammals are the same as they were in the fossil record. Animals and rodents are the exceptions.

What causes mammals to evolve quickly?

Predicting how different species will respond to rapid changes in their environment is a key goal of the study. The team looked at the characteristics of mammals that evolve fast and found the key factors to be habitat, social behaviors, diet and parental care.

The rate at which mammals evolve is vastly different to the rate at which social structures are in place. The evolution of mammals is much faster if they are social. This can be seen in ungulates which have evolved horns and antlers for fighting. Animals that live in the water, including whales, are fast evolvers. They track changes in the environment more closely than meat eaters do.

The results of evolution in social versus solitary mammals really struck home to Prof. Goswami, who conducted most of the analyses while isolating at home for several months at the start of the COVID-19 epidemic.

The speed of evolution seems to be slowed down by parental care. Animals that require little primary care, such as horses and antelopes, evolve a lot faster than mammals that rely on caregivers in infancy. When animals are active, it makes a difference, with species with a strict schedule evolving slower than animals without a pattern.

The groups of mammals with the most species, rodents and bats, don't seem to evolve very quickly, suggesting that diversity in shape and number aren't closely related in mammals.

Why haven't scientists been able to find the fossils of the earliest mammals?

The team used the new data to reconstruct what the earliest mammals might have looked like. There are many fossil mammals from the right time period, but it's difficult to identify fossils that represent the ancestors or early members of the placental mammal group, which would have died out before the dinosaurs.

It's hard to know what features to expect in the earliest representatives of the major groups of mammals, and if scientists would recognize them in the fossils that are known. The new reconstructions show that the earliest members of all the major groups of mammals looked the same, regardless of whether they are the ancestors of rodents or elephants. This means that it will be very hard to identify the earliest fossils of placental mammals, but these new reconstructions will give better understanding of the subtle differences for scientists to look for.

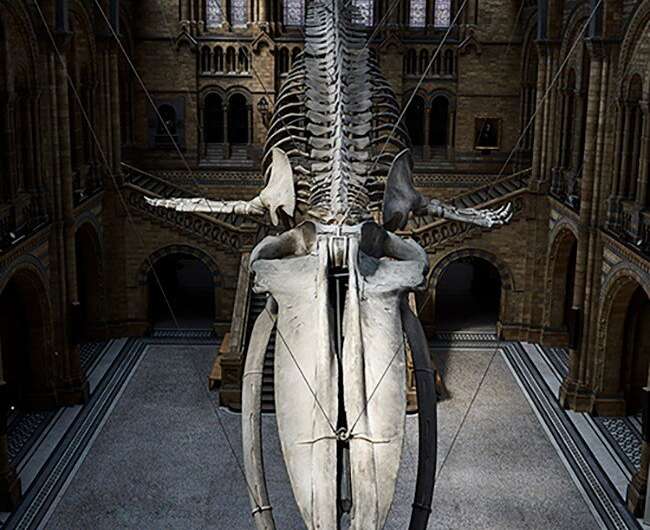

The museum collections allow us to predict the future by looking into the past. The blue whale in the Museum's Hintze Hall is one of the samples used in the study. In order to understand how past events have shaped mammal evolution over the Cenozoic era, we need these data.

The study, "Attenuated evolution of mammals through the Cenozoic," is in the journal Science.

More information: Anjali Goswami et al, Attenuated evolution of mammals through the Cenozoic, Science (2022). DOI: 10.1126/science.abm7525 Journal information: ScienceThe story is being updated by the Natural History Museum. The original story can be read here.