When Eric was a child, his parents woke him up in the dead of night. They told him to look out the window as a group of people pretended to be dead.

Dedace, who grew up on the Philippine island region of Quezon, said that his family did some prayers. My parents gave them a few cents.

The villagers were dressed somberly. Dedace was taken back to bed after his mother served him homemade ginataan, which was a soup of chicken, black pepper, ginger, root vegetables, and fruit.

The Philippine folk tradition known as Pangangaluluwa is known assouling. Adults and children travel from house to house pretending to be lost souls in purgatory on the nights leading up to and including October 31 and November 1st.

The performers used to sing about saints, lost souls, and Pangangaluluwa traditions. Money or rice snacks are included in these alms.

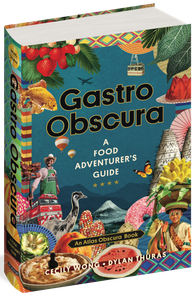

THE GASTRO OBSCURA BOOKDo you like the world?

An eye-opening journey through the history, culture, and places of the culinary world. Order Now

Prudente Sta. was a food historian in the Philippines. Villagers would drape themselves in white and black cloth and makeup to visit peoples' homes and ask for money in the early 1900s. It's not clear when the tradition started, but it came from the Catholic commemoration of All Saints' Day. While the practice may be related to trick-or-treating, it is a distinctly Philippine custom marrying two different beliefs about the afterlife.

Sta said, according to Roman Catholic tradition. Maria said so. The pagan faith continues to influence the present.

In the early 20th century, villagers dressed in white and black cloth and makeup to wake their children up at night. The costumes were simplified to just dark clothing when Dedace was a child. Dedace is a tour guide and cultural heritage advocate for the provincial government. In the 1920s and ’30s, some "souls" would steal fruit and chickens from homes that didn't have enough money. He jokes that the spoils were used to make ginataan.

Pangangaluluwa is still an important cultural ritual in the Philippines despite its evolution. A 2010 census showed that only 0.2 percent of the Philippine population affiliates itself with so-called "tribal religions", despite the fact that 86 percent of Filipinos practice Catholicism.

Sta. is a town located in the state of Sta. The church in the Philippines wanted their money. Those with less money were able to give to the church. The church charged for everything in those days.

Pangangaluwa is rarely practiced today. During World War II and the Marcos dictatorship, it became less common due to food insufficiency. The author of Food Holidays, a book and TV series that explores rural and indigenous food traditions in the Philippines, was born in Manila. During the American colonial period, trick-or-treating was popular in the capital.

It varies a lot depending on the region where it is practiced. In areas with no electricity, locals clean and lay flowers at the grave sites of their loved ones at candlelit parties. During typhoon season tents and mausoleums are used to protect the celebrations.

There are different treats for different locations. There are family recipes and what is available. It starts with the usual sticky rice and coconut milk base, which is steamed, boiled, or baked, and served in different shapes and sizes. taro, shredded coconut, fried fish, purple yam, and calamansi are some of the topping and filling ingredients. The simplicity and heartiness of Biko is what makes it a favorite. Pinaltok or dough balls made from ground sticky rice, coconut milk, and sugar are popular in Pangangaluluwa.

Families would wrap the rice cakes in banana leaves and place them in a bayong that they would lower out of a window. Most families leave the basket on the doorstep after the performance to allow the singers to get their treats. Adults might tell stories about deceased loved ones and take part in chismis to catch up on the lives of relatives overseas. It is a food that connects you even if you are far away. There is a person named Maria.

The living and dead are connected by rice. Rice cakes are offered to ancestors by Indigenous groups in order to improve their health and fortune. Sta. is a town located in the state of Sta. According to Maria, these rituals may be related to ancient beliefs that rice had a soul.

The cultural philosophy of pakikisama, an un translatable Tagalog term for the importance of being neighborly and generally kind to others, bonds people through Pangangaluwa. The Sariaya Tourism Council is trying to revive it.

The council has organized Pangangaluluwa for a long time. Kids dressed in scary costumes visit a local cemetery for treats and karaoke as well as elderly people's homes in a jeepney truck.

Dedace is a member of the council. The elderly patrons, who show their gratitude with donations, are especially those who come from abroad and stay in the Philippines for a vacation period until Christmastime.

Dedace feels like a kid again because the council will organize Pangangaluluwa once again. He says that Filippinos are very spiritual. It's a chance for us to connect with our dead relatives.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.