If you will, imagine a baggy filled with a mixture of powders and crystals.

The person presenting it admits the effects are different to what they are used to. We don't know if it is what they think it is. What are the consequences if it's not?

CanTEST is Australia's first and only fixed-site, face-to-face drug-checking service, located in the capital city of the country.

It led to the discovery of a drug never before seen in Australia and with no clinical information from anywhere in the world.

The challenge of pill-testing new psychoactive substances is significant. A chemical can be tested to see if it matches one of the thousands stored in databases.

When a fingerprints doesn't match, what happens?

The original baggy of powder was brought back to life.

Patrick Yates, a PhD candidate from the Australian National University's Research School of Chemistry, ran the sample through the first piece of equipment.

Even at a bush doof, FTIR works quickly and reliably. It shines a laser on the sample and compares it to a database of more than 30,000 chemicals.

Patrick's analysis didn't confirm a match, but he did suggest that it could be a new analogue of the drug. Patrick's intuition left him uncertain.

An instrument known as ultra-high performance liquid chromatography with photodiode array (UPLC-PDA) was turned on by a PhD student.

She used the lab to calibrate the machine to the 10 most common drugs.

Chemical X had to compare its sample to a known one. The UPLC-PDA test takes about four minutes to complete.

The sample looked similar to the standard, but it wasn't. The rate at which chemical X ran its race was the same, but it absorbed less ultraviolet radiation.

Neither ketamine nor 2-FDCK was real.

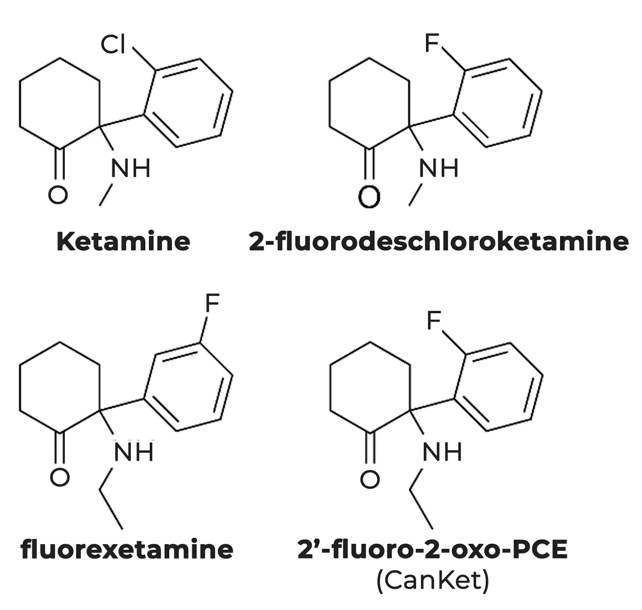

There is an emerging group of drugs known as arylcyclohexamines and one of them is ketamine.

The CanTEST team arrived at chemical X to beketamine-like.

Our band of peer workers advised extreme caution in using it, as the person who brought it in was unsure of its identity.

The full inquisition was just beginning, but that was not the end of the story.

The sample was smashed into pieces after it was subjected to a method called GC-MS, which means it was made to 'run another race'.

The presence of an isomer could not be ruled out, despite the correlation between the GC-MS data and the ketamine derivative.

The big guns needed to be brought out: a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer. Only a few people can speak the language and find answers.

The team found out that there were four hydrogens next to each other around the aromatic ring, meaning that it could not be fluorextamine.

There is only one chemical X, called 2′-fluoro-2-oxo-phenylcyclohexylethylamine. They hadn't seen this compound before.

It's difficult to say what a great piece of work this was. The UN Office of Drug Control, the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction, and several researchers from around the world were contacted by us.

They had never seen the compound before.

A global forum of forensic and analytical chemists reviewed their locally acquired data and provided information that supported our findings, as well as our colleagues at the ACT Government Analytical Laboratory.

There is a single report from China that was described by another name (2F-NENDCK). Our team has decided to call it CanKet because it is a bit of a mouthful.

We are now able to identify CanKet with certainty.

Thanks to knowing its chemical composition, we have a better idea of what we are dealing with.

David Caldicott is a senior lecturer and Malcolm McLeod is an associate professor.

Under a Creative Commons license, this article is re-posted. The original article is worth a read.