For decades, Syngenta has manufactured and marketed a widely used weed-killing chemical called paraquat, and the company has been dealing with external concerns that long-term exposure to the chemical may be a cause of Parkinson's disease.

Syngenta insists that its weedkiller does not affect brain cells in ways that cause Parkinson's and that scientific research does not prove a connection between the two.

The public narrative put forward by Syngenta and the corporate entities that preceded it has at times differed from the company's own research and knowledge, according to internal documents reviewed by the Guardian.

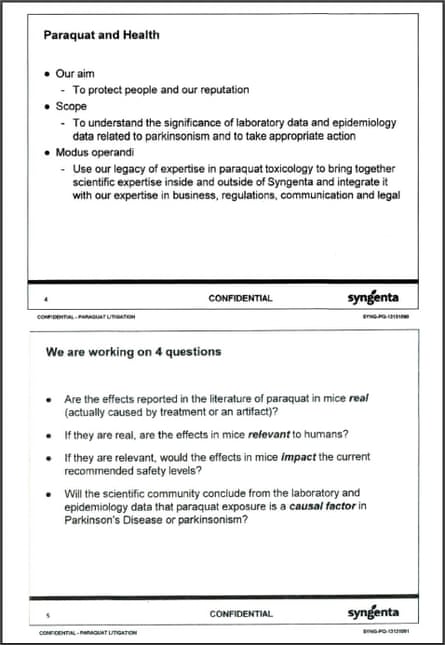

The documents reviewed don't show that Syngenta's scientists accepted and believed that paraquat can cause Parkinson's, but they do show a corporate focus on strategies to protect product sales.

The documents show that the company worked behind the scenes to prevent a scientist from sitting on an advisory panel for the EPA. Paraquat and other pesticides are regulated by the agency. The documents show that company officials wanted to make sure the efforts did not go to Syngenta.

The documents show that people were worried about being sued for the long-term effects of paraquat. The situation is a terrible problem for which a plan could be made.

Legal consequences have been predicted. Syngenta is being sued by thousands of people who claim they developed Parkinson's due to long-term exposure to paraquat. The successor to a company that distributed paraquat in the US is being sued by Syngenta. Scientific evidence does not support a link between paraquat and Parkinson's disease, according to both companies.

In a statement to the Guardian, Syngenta said that recent reviews performed by the most advanced and science-based regulatory authorities, including the United States and Australia, continued to support the view that paraquat is safe.

The studies that were reviewed did not show a link between paraquat and Parkinson, according to the statement.

According to the company, it doesn't believe that its former subsidiary that sold paraquat had any role in causing the illnesses of the people.

The companies gave the lawyers decades of internal records, including hand-written and typed memos, internal presentations, and emails to and from scientists, lawyers and company officials around the world. The New Lede collaborated with the Guardian to review hundreds of pages of the files that have not yet been made public.

In the 60s and 70s, scientists with Syngenta's predecessors were aware of evidence showing paraquat could accumulate in the human brain.

Syngenta hid information from regulators when it showed adverse effects of paraquat on brain tissue and downplayed the validity of other findings.

The records show that company scientists were aware of evidence that exposure to paraquat could impair the central nervous system and cause symptoms similar to Parkinson's. There are concerns about the effects of paraquat on the central nervous system.

As independent researchers continued to find more and more evidence that paraquat may cause Parkinson's, the documents describe what Syngenta called an "influencing" strategy. The strategy needs to consider how best to influence the regulatory environment.

A Syngenta document from 2003 states that paraquat must be vigorously defended to protect more than $400 million in sales. Ensuring Syngenta's freedom to sell paraquat was a top priority.

Syngenta created a website to provide positive product messaging, as well as dismissing concerns about links between paraquat and Parkinson's disease. Paraquat did not cross the blood-brain barrier even though the company had evidence that it was in brain tissue. The company doesn't use that language anymore.

Bruce Blumberg, professor of developmental and cell biology at the University of California, Irvine, said that it is unethical for a company not to reveal data that could indicate that their product is more toxic than had been believed. It shouldn't be allowed that these companies are trying to maximize profits. It's the scandal.

One of the most widely used weed killers in the world is paraquat, which competes with Monsanto'sGlyphosate for use in agriculture. It is used by farmers to control weeds before planting their crops. The chemical is used in many places in the United States. Paraquat popularity has increased as weeds have become more resistant toGlyphosate

Approximately 15 million acres of US farmland are used for it. The amount of paraquat used in the US has more than tripled over the past two decades.

The US has an estimated use of paraquat.

The Paraquat Information Center website states that the chemical can deliver safe, effective weed control, generating social and economic benefits, while protecting the land for future generations.

More than 1,200 safety studies have been submitted to and reviewed by regulatory authorities around the world.

Paraquat can be fatal if swallowed, as a tiny swallow can kill a person within days. There have been scores of deaths from ingestion of paraquat around the world. Only certified people are allowed to use it. There is a skull and crossbones symbol on the paraquat warning labels.

There is no risk to human safety if users follow directions and wear protective clothing, according to Syngenta. The company says that paraquat does not cause Parkinson's disease.

Dozens of countries have banned paraquat, both because of the acute dangers and mounting evidence of links to health risks such as Parkinson's. Paraquat is sold in more than two dozen countries by Syngenta.

The European Union banned paraquat after a court found that regulators did not thoroughly assess safety concerns. Although it is manufactured in the UK, it is banned in that country. In 1989 the chemical was banned in Switzerland. The home base for ChemChina, which bought Syngenta, is banned in China.

Syngenta and other chemical companies have said that paraquat can be used safely. The EPA said last year that it would allow farmers to use paraquat.

The spread of Parkinson's has become one of the world's fastest-growing neurological disorders, raising concerns about possible ties between the two diseases. ThePrevalence of Parkinson's more than doubled from 1990 to 2015 and is expected to continue to expand. Many researchers consider toxins in air pollution and pesticides to be risk factors for the disease.

Parkinson's has been ranked among the top 15 causes of death in the US by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The death rate from Parkinson's has increased in the United States over the past two decades. It is a fast-growing neurological disease.

Parkinson's is a disease of the central nervous system that can cause tremors, a loss of balance and coordination, and difficulties speaking. Parkinson's symptoms can be caused by the loss of dopamine- producing neurons in the substantia nigra. The brain can't transmit signals between cells without enough dopamine production.

The rise of Parkinson's disease has exacted an enormous toll on tens of millions of people, according to a 2020 book written by a neurologist.

Research shows that exposure to paraquat can cause Parkinson's disease.

Paraquat is considered to be the most toxic of all the pesticides.

The weight of evidence shows that paraquat does not cause Parkinson's, according to Syngenta. An update to the US Agricultural Health Study is supporting the company's position. Prior research has linked paraquat to Parkinson's, but the 2020 AHS looked at a bigger group of people.

There isn't a properly designed epidemiological study that shows a link between paraquat and Parkinson's disease

Despite hundreds of studies being conducted in the past 20 or so years, a link between Paraquat and Parkinson's disease has not been found.

1924. The roots of Syngenta go back to Imperial Chemical Industries. The company expanded through a number of acquisitions. 1993 was a long time ago. Several businesses were transferred into a new company called Zeneca, which later merged with a pharmaceutical company to form a new company called Amaranth. The year 2000. Syngenta AG was created by the merger of certain business lines of the two pharma companies. A new year. ChemChina bought Syngenta.Quick GuideShow

Gramoxone, Syngenta's paraquat brand, was launched in the UK and the US in 1962 and 1965, respectively.

The company's scientists were beginning to see early signs of possible problems with the product. An ICI researcher told a colleague that company tests on laboratory animals found exposure to a chemical compound related to paraquat appeared to affect the central nervous system.

A 1964 ICI study on rabbits found that exposure to paraquat could cause symptoms such as weakness and incoordination. Rats and mice exposed to large amounts of paraquat showed effects on the central nervous system, with various impacts, including some animals showing a stiff gait.

Paraquat poisoning deaths began to mount around the world in 1968, as many people used the pesticide as a way to kill themselves. According to the documents, there were multiple autopsies and analyses that showed paraquat was accumulating in brain tissue in people who had eaten small amounts of paraquat.

More evidence of the chemical's ability to move into the brain was found in the early 1970s. Field workers exposed to the chemical were complaining of health problems, and the documents show that some state regulators were concerned about the long-term effects on workers who might inadvertently lick small amounts of paraquat. Some people inside the EPA were rumored to be in favor of banning paraquat.

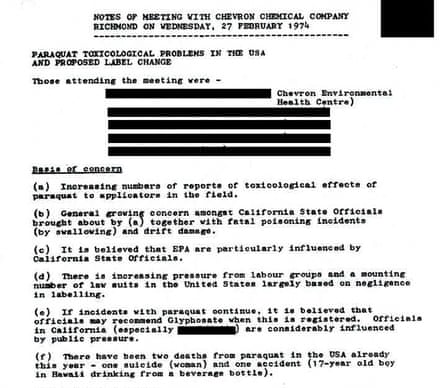

The labeling on Gramoxone needed to be stronger in order to warn users of the dangers. There were notes from a February 1974 meeting that referred to the paraquat toxicological problems in the USA.

ICI was concerned about market repercussions outside the US from added warnings, but agreed to the changes.

There is evidence now that paraquat could cause industrial injury and it should be recognized that Chevron could face suits totalling millions of dollars, according to notes from a follow-up meeting.

Fears of Chevron were growing. There were studies indicating the potential for central nervous system effects from paraquat in a July 1975 letter from a Chevron toxicologist. ICI was asked if they had any information on the question of permanent injury from paraquat or any follow up evaluations after spraying.

According to the notes from the October 1975 meeting, the chronic effects of paraquat sprays were reported to be an injury to the central nervous system.

There may be a need for long-term toxicity studies or an epidemiology study, according to the notes. In the same meeting, it was noted that an autopsy of a paraquat poisoning victim had found damage to the motor neurons, but it was not clear what caused this. Motor neurons are cells in the brain and spine that communicate with each other.

In 1975, an ICI scientist wrote a letter to theChevron toxicologist, telling him about the possible effects of chronic effects. I don't think a satisfactory investigation can be made for this problem. To be as definitive as possible, any study must be free from doubts.

As the companies fretted, the bad news continued to build: a 1976 autopsy of a farmworker showed "degenerative changes" in the brain. The autopsy said that the changes were likely caused by lung damage. There was a gap in our knowledge of the effects of paraquat exposure.

By 1985 the science on paraquat health effects had become the subject of vigorous research by independent scientists and the findings were ringing alarm bells.

A study by a Canadian researcher found a high correlation between Parkinson's and the use of pesticides. The memo said that paraquat was very similar to the byproduct of synthetic heroin called MTPT, which causes Parkinson's by killing dopaminergic neurons in the brain.

The author of the Canadian study warned of an increase in Parkinson's disease due to the introduction of paraquat-like pesticides.

It was warned in the memo that paraquat could turn out to be a huge legal liability like the one that befell theAsbestos company.

The memo states that the financial risks of selling a product which contributes to a chronic disease were highlighted by theAsbestos situation. inson's can last for a long time.

R Gwin Follis, the retired chairman of Standard Oil, which became known as Chevron in 1984 wrote to GM Keller, the chairman of Chevron, saying that he couldn't think of anything worse for the company to have to deal with. The company stopped selling the drug in 1986.

According to a statement to the Guardian, the decision to exit the paraquat distribution business was made solely for commercial reasons and did not relate to any health concerns.

The company said that it met or exceeded all federal and state requirements for product safety testing before and after paraquat's release.

In the 1990s and into the 2000s, the research on paraquat and Parkinson's expanded inside and out of Syngenta. There is more evidence that the chemical paraquat could cause Parkinson's.

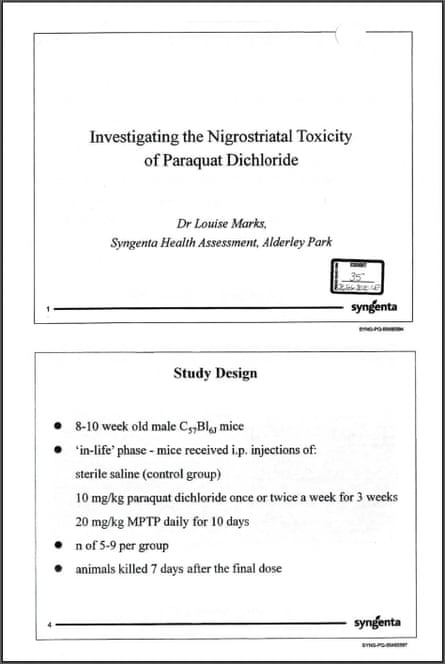

The external pressures on paraquat were noted by Syngenta and it decided that its own scientists should do more studies to see if they can come up with the same results. According to an internal Syngenta presentation, the Syngenta science team avoided measuring the levels of paraquat in the brain since they wouldn't be seen in a positive light.

The data generated will be used to build a scientifically robust, defensive position for paraquat in response to the issues already in the scientific literature, and to questions raised by the media, customers and regulatory authorities.

If the Syngenta ambitions for the product are to be realised, there needs to be a solution to the paraquat exposure and Parkinson's disease claims.

Syngenta began honing a broader "influencing" and "freedom to sell" strategy along with making a plan to generate data for its defense. The objectives were made clear in a 2003 eight page document.

The chemical was under scrutiny in Australia and the EU. Changing regulatory policies pose a threat, including that regulators may replace higher hazard products with lower hazard products.

Companies that want to sell a chemical have to prove that it's safe. The US regulatory system mostly uses the opposite approach of keeping a chemical off the market.

Syngenta said it would take several steps to influence regulatory policy.

The company wants to improve its product image through targeted collaborations with influential people.

The company will contribute substantively to the literature, including for studies being done for submission to the UK's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, and the Agricultural Health Study in the US, according to internal communications.

The data from Syngenta's internal studies began to show up. The first internal study done in 2003 was designed to dose mice with paraquat and measure any loss of dopamine in the brain. The tests used by Syngenta did find losses, but they used a different method for analyzing them than independent scientists use. The impact of paraquat on the animal's brain was found to be not statistically significant by Syngenta.

The Syngenta scientist who led the animal studies, Louise Marks, repeated those studies using the more accurate, automated technique that independent scientists use.

Outside scientists had found that when using an automated analysis technique, paraquat resulted in a statistically significant loss of brain cells. The results were the same. Marks wasn't reachable for comment.

The deposition testimony given in the current litigation by Syngenta scientist Phillip Botham, which has not previously been made public and during which a judge was not present, indicates that company officials would not tell the EPA of Marks' research findings until around 15 years later. According to a transcript of Botham's testimony, the company only told the EPA about the Marks' data after a lawyer threatened to send the evidence to the EPA himself.

The Marks studies involved a model in which a particular breed of mouse was injected with a lethal dose of paraquat. It's not relevant to evaluate the safety of those using paraquat.

According to the deposition, Syngenta knew that the statements it made on its website weren't true.

When asked if that information was true at the time it was posted on the website, Botham admitted it had some incorrect information. He said that the communication had not had a chance to catch up with the science that was still evolving. He said that part of the reason the company didn't report Marks' findings on its website was because of the different results that came from subsequent research.

Lobbying for and against who the EPA looked to for scientific advice is part of the strategy. An open position on an important agency scientific advisory panel was being considered by the EPA in 2005. At the time, there was strong evidence that paraquat could cause Parkinson's Disease.

It's important. In June 2005, a Syngenta senior research scientist wrote to his colleagues that they didn't want to have a person on the core panel.

According to company emails, Syngenta asked a regulatory policy expert at the industry lobbying group CropLife America to trash the work of a colleague. Syngenta officials wrote what they wanted to say to the EPA.

One Syngenta executive wrote to colleagues that it was difficult for Ray to provide comments that weren't used against them.

It was going to be difficult to pin something specific on D C-S.

The company decided to keep the information secret. The company didn't want the public or the EPA to know that Syngenta was involved.

A Syngenta regulatory affairs executive asked that the comments be handled in a way that they couldn't be attributed to the company. He suggested that the communications to the EPA should be informally submitted.

For many, many of our projects it would be a real disaster to have her on the platform.

It was suggested that the EPA should be told that the person who made the statements was someone who made "overly dogmatic" statements.

The concerns that were communicated to the EPA were not mentioned. Someone else was chosen to serve on the panel.

Similar efforts were made to influence the roster of scientists selected by the EPA for a pesticide advisory panel. CropLife was advised by Syngenta to tell the EPA about the use of her research program for anti-pesticide advocacy.

The scientist supported by CropLife was selected for the panel.

She was not surprised by the company's actions against her. She said Syngenta representatives had tried various tactics to intimidate her, and at least once tried to lure her with an invitation to collaborate on research.

She said in an interview that she was followed around by people. They weren't happy with me. Our research shows that when you give paraquat to rodents, you will see a loss of dopamine cells. The hallmark of Parkinson's disease is that.

They didn't like the data. They were concerned about a threat to a large market.

She said she is not againstpesticide. She wants to remain in the middle. I go out of my way to stay in the middle. I allowed myself to be guided by the data.

Syngenta disagreed and took exception to the portrayal of the correspondence.

A June 2021 trial in Illinois would have been the first major court challenge to Syngenta and Chevron over the Parkinson's link to paraquat.

According to a disclosure in the company's financial statement, Syngenta agreed to pay $187 million to settle a number of lawsuits just as the trial was about to start. As part of the settlement, the company didn't admit liability. It is not known how much was paid.

More than 2,000 other people with Parkinson's disease are being pressed for compensation by other lawyers.

Farmworker groups, Parkinson's scientists and others who brought the court challenge welcomed the EPA's agreement to reconsider its assessment of paraquat. The agency will have a revised report out in a year on the health risks and costs associated with paraquat.

Ted Thompson, senior vice president of public policy at the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research, said in an email that their research partners have studied the evidence showing paraquat's association with neurological degradation.

The federal government and the EPA should use every tool at their disposal.

The agency's position is not clear if the EPA's review will change it. According to the draft human health risk assessment by the EPA, there were only 71 studies that were relevant to the agency.

The agency has not found a link between paraquat exposure and adverse health outcomes such as Parkinson's disease, according to its website.

Paraquat use continues while the agency conducts its assessment.

The New Lede is a journalism project of the environmental working group. Carey Gillam is an author and the managing editor of the New Lede.