There are large quantities of naturally occurring ice-like deposits made up of water and methane gas on the seafloor. Climate scientists have been wondering if the methane hydrate could "melt" and release huge amounts of methane to the ocean and the atmosphere as ocean temperatures warm.

Scientists at the University of Rochester, the US Geological Survey, and the University of California Irvine have found that methane released from decomposing hydra is not reaching the atmosphere.

The study was carried out by John Kessler, a professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and a former research scientist in his lab.

In the mid-latitude regions where the study was conducted, no signatures of methane being emitted to the atmosphere were found.

Methane forms, Hydrates, and degrades.

Methane has no effect on Climate. It acts as a heat-trapping gas. Today's atmosphere contains methane from human activities, as well as methane from wetlands, wildfires, aquatic environments, and coastal zones.

Huge storehouses of methane in the form of methane hydrates can be found in the ocean.

There is a lot of methane locked up in gas.

Climate change could be worsened by the release of even part of this storehouse.

Kessler says "Imagine a bubble in your fish tank going from the bottom of the tank to the top and exploding and releasing whatever was in that bubble to the air above it."

Methane and water meet at high pressure and low temperature. In the parts of the ocean located in the mid-latitudes, hydrates can only be stable at depths of about 500 meters. Hydrates become more stable when they are deeper in the water.

The upper stability boundary is a "sweet spot." It is the most vulnerable to melting due to the fact that it is the shortest distance a bubble of methane would have to travel before it reaches the atmosphere.

The researchers didn't see evidence of methane being released to the atmosphere.

The source of methane is being fingerprintsed.

In order to conduct their study, the researchers collected samples from various depths in the mid-latitude regions of both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. They were able to identify the source of methane in the water.

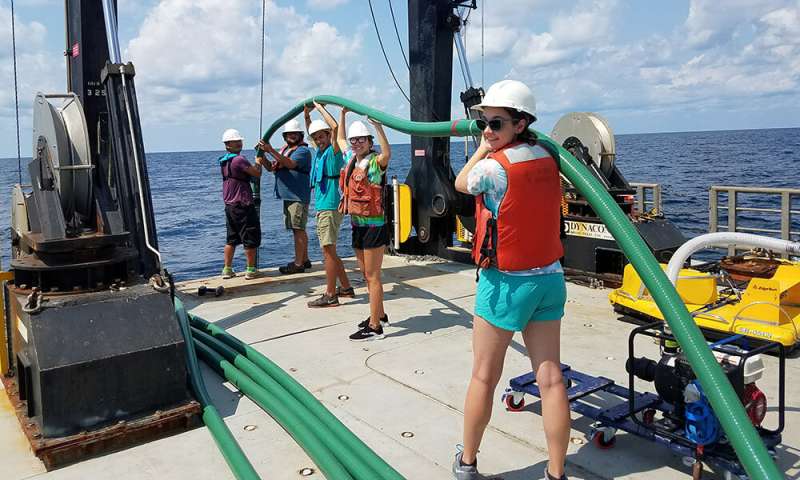

They need a lot of water to make a single measurement. The researchers used a giant hose to collect the samples and then used a new technique to extract methane from them. Kessler's lab on the River Campus was the place where the researchers compressed the methane into cylinders.

Ancient methane is being released from the ocean. They didn't find a lot of ancient methane in the water. They concluded that methane can be dissolved in the deeper waters and then turned into carbon dioxide by the ocean microbes.

Kessler's group found that these processes are active in the mid-latitude regions and that similar processes helped to mitigate the effects of the oil spill.

Kessler says that carbon dioxide can be incorporated into other carbon basins in the ocean. It would take a long time for carbon dioxide to be released into the atmosphere and for the warming to be less severe.

The work in Kessler's lab focused on methane hydrate in the ocean. Hydrates can be studied in the cold waters of the north because they have a shorter distance to travel to reach the atmosphere.

The news that underscores the work that remains is what Kessler calls the good news. In order to reduce sources of methane to the atmosphere, we can focus more of our attention.

More information: DongJoo Joung et al, Negligible atmospheric release of methane from decomposing hydrates in mid-latitude oceans, Nature Geoscience (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-022-01044-8 Journal information: Nature Geoscience