Barry Groenteman is sitting in his boxing gym reminiscing about the times he used to visit his grandma.

He would often find an older man shadowboxing in the hall with the nurses when he went to see her.

The Star of David was on his ring. My grandmother would whisper "That's Ben Bril"

The young Groenteman was introduced to a man who would have a huge impact on him.

Bril grew up as a Jew in Amsterdam and became a boxer.

There are no comparisons left. Groenteman was a child. Bril was born 100 years ago. His life was turned upside down when he reached his 30s.

The Dutch boxing world will come together to celebrate the return of the Ben Bril Memorial night.

A serial national champion was forced into hiding and then sent to the Nazi concentration camps by a former olympic team-mate.

Bril was the second youngest of seven children and lived in a poor part of Amsterdam.

Steven Rosenfeld, a relative of Bril's and author of a book about his life, said that it was a tough upbringing.

"They lived in tenements, he didn't sleep in a bed, he slept on straw, they didn't have a toilet, he had to carry buckets down to the street."

For the young Bril, fighting was a part of daily life. There were scraps with friends of course, but also clashes with rival groups from different communities in the tightly packed city, according to Ben Braber, a historian who has written extensively about Jewish life in Amsterdam during the inter-war years.

While some of his friends were fighting, Bril turned to sport.

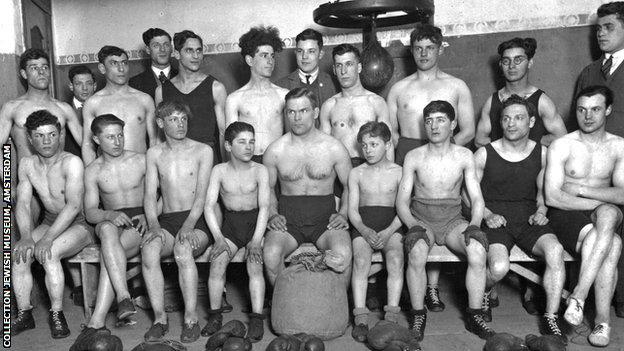

Before World War II, boxing was very popular in the Jewish Quarter.

It was hard for some boys to fight for gamblers. They were popular because they were an escape from poverty.

The art of self-defence requires courage, stamina, quick reactions and also technical skills.

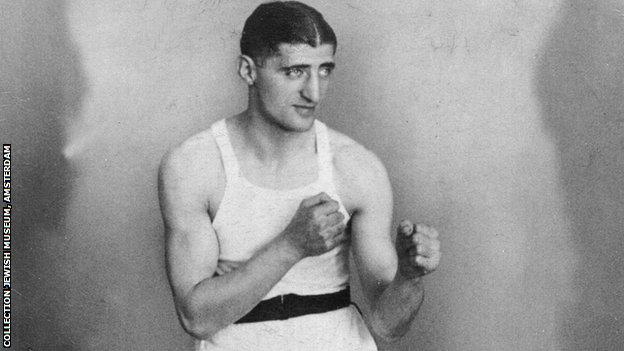

The career of Bril began when he was selected to fight for the Netherlands at the Amsterdam Olympics at the age of fifteen.

There are some suggestions that he had to fudge his birthdate in order to get into the Olympics, but he made it to the quarter-finals in his weight class.

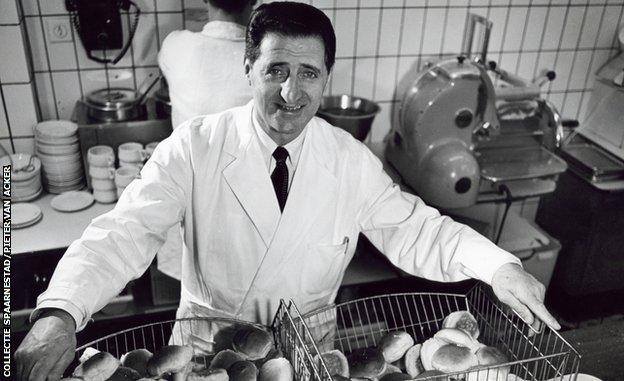

Bril used his new job in a butcher's shop to help develop his sport.

He told me that he used his left hand to strengthen his jab even though he was right-handed.

He was told to dip Ben's hands into the brine.

Bril won eight Dutch titles and national fame during the 1920s and 1930s.

Life in Amsterdam would change a lot over those years.

Discrimination against Jews became more common due to the economic crisis and rise of Nazi Germany.

Bril was left out of the Dutch team for the Olympics in Los Angeles because of his domestic success.

He was blacklisted by anti-Semites on the Dutch national boxing committee after he didn't understand what had happened.

In 1935 Bril claimed that his greatest success was the source of the Star of David ring he wore as an old man.

The second edition of the Maccabiah Games for Jewish athletes from around the world was held in Tel Aviv.

He and Appie de Vries both won gold medals and returned to a hero's welcome.

Bril wore the Star of David on his shorts in order to match the ring he had won.

Bril was not the first boxer to wear the Star in that way.

The great 1920s American lightweight, nicknamed "The Ghetto Wizard", did it in his heyday.

Barry Groenteman wanted to follow in the footsteps of the man who inspired him by displaying the Star of David in the ring.

In the 1930s Netherlands, Bril identified himself in that way.

He said that he identified himself as being Jewish, but he also wanted to be identified by others as being Jewish.

Bril was still wearing the Star in the ring when he handed out publicity photos of himself in trunks.

Bril's first motivation in wearing the Star was an expression of his sports accomplishment, not a political statement, according to the author.

He wasn't afraid to act on his own, even though he was aware of the situation around Europe.

Bril went to Germany with a group of Jews.

The Nazis were in power for a long time. The state had started discriminating against Jews. The atmosphere was hostile and daily life was getting harder.

Bril was horrified by what he saw

Bril told a Dutch newspaper that they saw brown uniforms, swastika flags, and the word "Jew" on businesses.

As long as this regime is in power, I won't go to Germany.

He turned down the chance to go to Berlin for the Olympics because he was hurt by being overlooked for LA four years before.

As his fame grew, Bril married a woman. They opened a sandwich shop in the city after having a child.

Everyone in the country was affected by the outbreak of war in Europe. Germany invaded the Netherlands in 1940.

Life for Dutch Jews became more restricted and under threat as time went on.

Historian Braber says that in 1941 stricter regulations were put in place to separate the Jews from the rest of the population.

Bars and cafes tried to ban Jews from their premises, which ended in violence, because of restrictions on which public spaces Jewish people could enter.

The creation of a number of Jewish defence groups was sparked by this.

The Jewish district of Amsterdam was invaded by the Dutch Nazis.

There was a fear that synagogues would be the next target after attacks on Jewish homes and businesses the previous day.

The defenders were prepared for a fight with anything they could get their hands on.

According to Braber, this time it was even more violent and bloody and resulted in the death of at least one Nazi and caused repercussions against the Jewish community.

Many of the men who were rounded up and deported were dead within a few months.

Although Braber was told by a friend of Bril's that Bril was involved, it is unlikely that the champion took part in the fight.

Bril was told not to go because of his fame.

The brief confrontation in Amsterdam's Waterlooplein square, with Jewish fighting groups at the core, was a stark example of how life in the city had changed.

In July 1942, after it became compulsory to wear a yellow star, the first deportations of Dutch Jews took place.

Nobody in the Netherlands knew what was happening in the Jewish internment camps.

After the war, we knew more about gas chambers and camps. Some people who were called up for deportation went into hiding.

Bril and his family were part of that number. The decision to hide was perilous, as Braber points out. You have to think about all of these.

Despite the danger, the Brils were often out and about.

They were betrayed and held in custody by Sam Olij, who was a teammate of Bril's on the Olympic boxing squad of 1928.

Bril had also boxed with Olij's sons in Amsterdam, but the Olij family had become committed Nazis. According to Dutch sports historian Jurryt van de Vooren it was Olij's son Jan who arrested Bril and his wife and son.

They were sent to the camps. Anne Frank was one of the 50,000 people who died in Bergen-Belsen.

The worst kind of betrayal in Dutch sport was committed by Olij. He died after nine years of imprisonment and his son Jan fled to Argentina.

Bril's life in the war is filled with many moments, but one stands out. He acted instinctively during the moment that was fraught with danger. We can hear about it through Bril's own words because he told Braber about it in the 1980s.

The boy tried to escape but they caught him.

He was put on a rack and given 25 lashes of a whip. The commander ordered the boxer to step forward.

I didn't want to carry out the punishment. The commander told me that if I didn't hit him, he'd get 50 lashes.

The commander got angry. He started beating with the whip after grabbing it. I went back to my place of employment.

It's not clear why Bril didn't suffer consequences for his refusal to carry out the order, but those who witnessed it were absolutely certain of what they saw.

"Ben Bril was the only man I saw during two and a half years in concentration camps - or heard of - who risked refusing to carry out a formal order of the SS."

The historian said it was a very brave act.

Bril would have to fight in two different camps. He was a target because he was a famous boxer.

Bril told of a life-changing moment. He said that he boxed for his son.

He was going to fight against a man who was appointed by the Nazis to guard and control the other prisoners.

Bril was asked not to hit him. He agreed if the man helped him get medicine and didn't beat the inmates in his block.

Bril's son overcame his illness as a result of the man complying.

The fights were staged to entertain the camp authorities. According to Braber, those taking part may have gotten some benefits.

Groenteman made a powerful television programme about Bril's story and remembers being shown some of the papers detailing the fights in Camp Westerbork.

He knows a lot of the people he saw.

The scariest thing was that they were the same as the schedule papers that hang in changing rooms now. It was difficult.

The majority of Bril's family died in the Holocaust, but his son and wife survived.

In January 1945, from Bergen-Belsen, the family were included in a prisoner exchange that saw them taken first to Switzerland and then to a UN camp in Algeria.

After the war, Bril didn't return to the ring as a fighter, but he did return to the ring as a boxer.

He was a senior official in the sport and acted as a referee and judge at fights around the world.

He went to the Olympics in Tokyo in 1964 in which he leaped into the ring to protect a fellow referee who had been punched by a competitor.

There was a dispute with the boxing authorities in the Netherlands that caused him to miss the 1972 games.

At the beginning of the careers of some of the greats, he was an official at ringside or on the canvas.

Bril passed away in 2003 at the age of 92. Four years later, a memorial night was held.

The first time Groenteman appeared at the Carre was in 2011. He fought with the Star of David to honor his family and the man who inspired him as a child.

He says that the fight he fought that day was the best of his entire career.

From where they came from, people get their strength from their religion. The Star on my trunks gave me more power.

We're raised up with the idea that we should never walk away from where we came from. He stood for who he was.