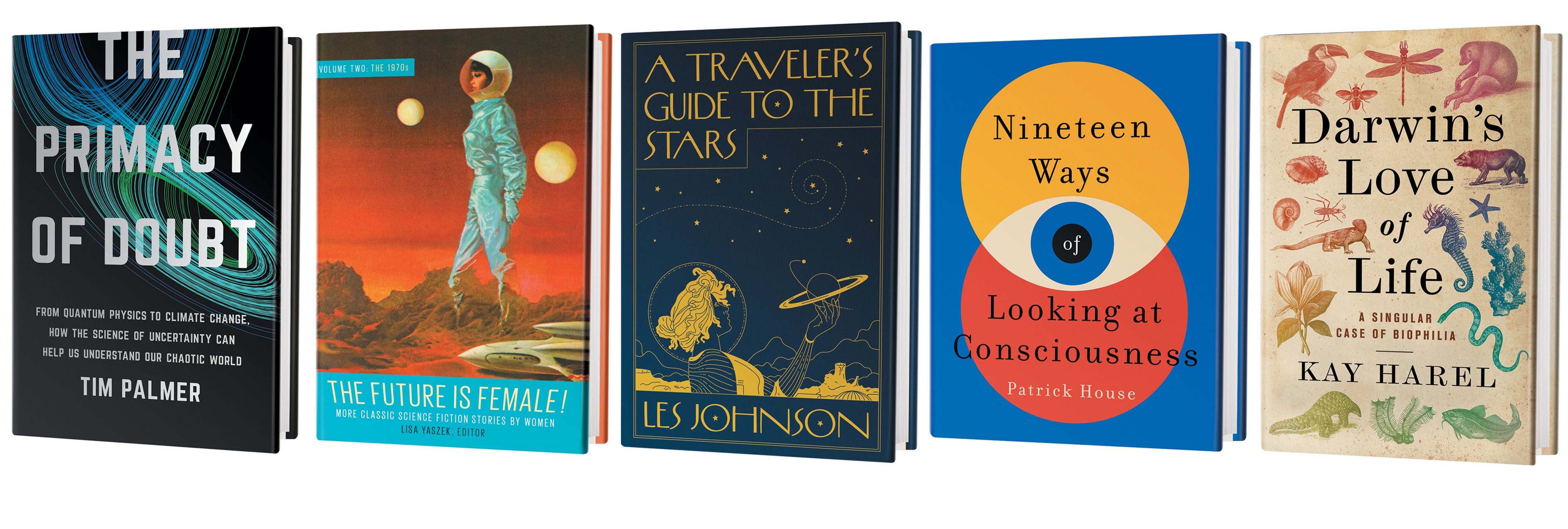

There are new books on the power of doubt, science-fiction icons, consciousness, and more.

Politics and social media have become known for boiling down complex issues into simple, bite-sized nuggets. Climate physicist Tim Palmer argues in his new book that the science of uncertainty is not appreciated by the public. He says that embracing uncertainty and using the science of chaos could help us understand the world better.

The first section is a dense discussion of major questions and concepts in physics that illustrates how, among other things, systems can go from a stable state to a wildly chaotic one with little warning. Palmer helped tomodernize the process of predicting the weather. He explores the history of the forecast starting with the first public storm warning in 1861 that used data from telegraphic stations in the U.K.

Probable forecasts predict the chance of rain in an hour and give the "cone of uncertainty" for hurricanes. If we needed certainty to make choices, these tools wouldn't exist.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change won a prize for their work in 2007, and Palmer is one of the researchers who won. There is a mixed bag in his chapter. Reducing uncertainty is important to figuring out just how bad things could get, such as whether clouds will speed up or slow down. Palmer calls for a "CERN for climate change" that will focus on modeling how rising carbon dioxide and natural shifts in the climate will interact over the next couple of decades. It could help predict long-term droughts in Africa's Sahel region, which could lead to famine.

The uncertainties of climate change are difficult to frame. He starts the chapter by asking if the maximists are right to suggest we're in an emergency and should decarbonize as quickly as possible. He writes that the truth is somewhere between right and wrong. If atmospheric carbon dioxide were doubled, it would warm the planet by one degree. Without taking into account feedback loops, such as the loss of ice cover or more water in the atmosphere, that's how much it's going to cost. He thinks this is not something to make a big deal of.

The view of a planet that is already one degree warmer than in preindustrial times is alarming. The shift has caused unprecedented heat waves on every continent, set the American West ablaze with ferocious intensity, and led to deadly deluges in areas that have never experienced such extreme back-to-back rain. Palmer encourages his readers to reference the most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which paints an increasingly dire picture. One of the lead authors on the report said that adverse impacts are being much more widespread and being much more negative than expected. It can obscure the larger picture. It's impossible to ignore the fact that readers are looking for reasons to brush off the importance of climate policies.

The fossil-fuel industry, politicians and a small group of scientists have played up uncertainty with the intent to delay meaningful carbon regulation. He brushes off the reality that uncertainty is used against society rather than it's benefit.

He is a writer and editor. The climate editor is at Protocol.

The Future Is Female! Vol. 2: The 1970s: More Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women by Lisa Yaszek

Library of America, 2022 ($27.95)

You can sign up for Scientific American's newsletters.

The first volume of Library of America's "The Future Is Female" series was a collection of science-fiction stories written by women. The 1969 Ursula K. Le Guin story suggested our Space Age future could be alienating. "Nine Lives" suggests that advanced tech and interplanetary adventure could make real human connection all the more rare. It imagined how we would feel in the future.

In the second volume of the book, women talk about sex, power, the banal routines of domestic life, and whether or not they can achieve true equality. Women whose choices are circumscribed by societies that are pointedly like are the focus of the feminist stories here.

50 years later, the results still don't seem right. The cleaner of government masturbation stalls narrates the story of Piserchia's "Pale Hands", which is set in a 2021. A planet where women have thrived without men for 30 generations suddenly becomes a place where men and women are treated equally. He says that seals and men are the same type of animal. In the beginning story, "Bitching It," Sonya Dorman imagines a world where women are bored and men are passive.

The prescient "The Girl Who Was Plugged In" by James Tiptree, Jr. is one of the works in this bold collection. Eleanor Arnason's book dramatizes a sci-fi author's effort to write a story that grows richer the more it draws from her own life. The future is personal in their hands.

A Traveler’s Guide to the Stars by Les Johnson.

Princeton University Press, 2022 ($27.95)

It will take a long time to explore a distant star. NASA scientist Les Johnson helps us understand the enormity of sending humans light-years from home by laying out the opportunities and limitations of existing technologies. The way we live on Earth will likely change as a result of the advances we make in pursuit of interstellar travel. If our predecessors had not done science for the sake of science, we wouldn't have cell phones or electricity.

Nineteen Ways of Looking at Consciousness by Patrick House.

St. Martin’s Press, 2022 ($26.99)

The book doesn't try to explain what consciousness is, how it arises, or why. Patrick House sketches an outline for how we might look at who we are from the inside out, using observations from neuroscience, quantum mechanics, and beyond. A recurring example is the case of a teenager's laughter during brain surgery. House's Collage forms a picture of our minds that is far more complex and confusing than the sum of its parts.

Darwin’s Love of Life: A Singular Case of Biophilia

by Kay Harel. Columbia University Press, 2022 ($26)

Kay Harel happily diagnoses Charles Darwin with a single case of biophilia, or profound love of life, that engenders empathy, creativity and an intuitive sense of truth. Biophilia is the root of Darwin's genius and the influence behind everything from his love of dogs and fascination with the Drosera plant to his rejection of mind-body dualism. A refreshing take on Darwin's legacy can be found in Harel's focus on the confluence of his life.

The original title of this article was "Reviews" in Scientific American.

The article is titled "Scientificamerican1012-74."

World-changing science is what you'll discover. We have articles by more than 150 winners of the prize.

Subscribe Now!