The structure of a mysteriousprotein complex inside the inner ear has been discovered by scientists.

60 million roundworms needed to be grown to solve the decades-old puzzle.

The only way the team could accumulate enough of theprotein was to turn to another source.

"We spent several yearsOptimizing worm-growth andProtein-isolation methods, and had many 'rock-bottom' moments when we considered giving up," says co-first author Sarah Clark.

The exact makeup of the TmC1 complex has remained a mystery for some time.

Eric Gouaux is a senior author at OHSU and he says that this is the last sensory system in which the fundamental machinery has not been understood.

Thanks to the new research published in Nature, we now know that a tension-sensitive ion channel that opens and closes depends on the movement of hairs in the inner ear.

The researchers found that the protein complex resembles an accordion, with both sides covered in folds.

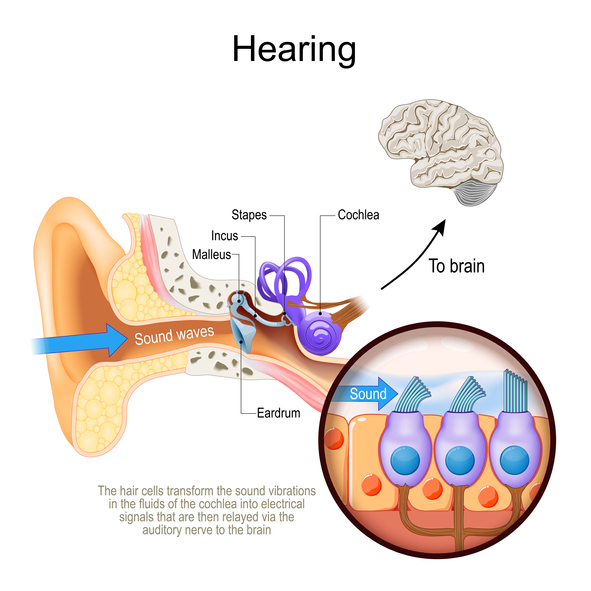

Three of the body's smallest bones are jiggled by sound waves when they hit the eardrum. The ossicles hit the snail-like cochlear, which in turn brushes tiny hairs called stereocilia.

These stereocilia are embedded in cells that have the ion channels formed by the TMC1 complex that open and close as the hairs move to send electrical signals to the brain.

Peter Barr-Gillespie is a national leader in hearing research who was not involved in the study.

One day researchers will be able to develop treatments for hearing impairments.

Hearing loss and deafness affects more than half a billion people. Understanding the nature of hearing can help researchers find ways to support, treat, or prevent hearing loss.

The paper was published in a journal.