Around 67 million years ago in what is now North Dakota, a duck-billed dinosaur died and crocodiles descended on it to mark up the bones. Evidence of the predator's feast can still be seen in the dinosaur's fossils.

The bite marks may help explain how the dinosaur became a mummy. Dinosaur mummies with well-preserved skin and soft tissues may be more common than previously thought.

The assumption used to be that if you wanted to get a mummy, you had to be buried quickly. The remains of a dinosaur would be protected from the elements and scavengers once they were covered in the mud. The animal's skin could mummify.

According to Drumheller, if you have a predator partially eating the remains, that can help the long-term stabilization of things like skin.

The associate professor of ecology at the University of Reading was not involved in the study. It is possible that the skin and bones could have been left there for a while with the skin drying out in the sun before being covered over.

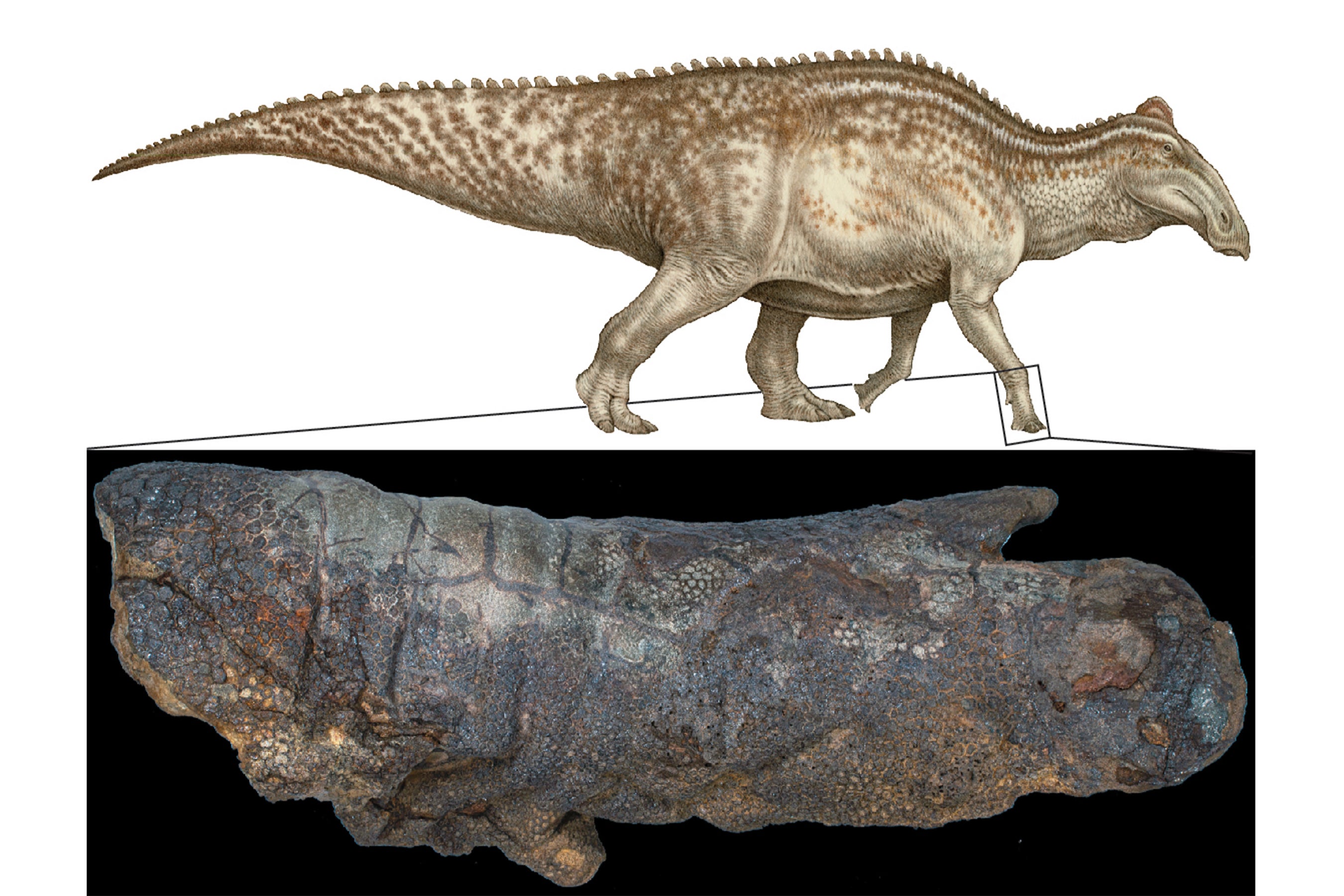

A well-known Edmontosaurus fossil was examined by Drumheller and her colleagues. The specimen was found on a ranch in southwest North Dakota. It was excavated from the Hell Creek Formation, a geological formation that formed at the end of the Cretaceous period and the beginning of the Paleogene period.

The Edmontosaurus fossil is missing its head and the tip of its tail, but the rest of the animal's bones are still intact. The bones of the dinosaur are covered with preserved skin.

The skin is a deep brown, almost brownish black, and it has a bit of a shine to it because it has a lot of iron in it. She said it almost looked like it was shiny.

The fossil of Dakota was not completely free of the rock surrounding it when it went on public display. Fossil preparators discovered markings that looked like bite marks when they cleaned the specimen more thoroughly in 2019. There were bite marks on the tail and the pink finger of the right fore limb.

When the team started looking for bite marks on Dakota's bones, they found distinct marks on his bones. It's difficult to find bite marks inskin. As the skin is bitten into, it stretches and tears, which can warp the tissue further. To find out what bite marks on dinosaur skin would look like, the team looked to forensic studies.

It isn't a perfect comparison because dinosaur skin is more durable than human skin.

You can sign up for Scientific American's newsletters.

The researchers found that Dakota's tail was probably made by teeth or claws dragging through the flesh. There is a chance that a reptile, such as a large deinonychosaur, may have left marks on the ground. The team found more than a dozen puncture wounds on Dakota's right hand and fore limb and noted that the skin of the latter had been partially peeled back.

Dakota's carcass remained unburied and vulnerable to scavengers for some time after his death, but if he wasn't quickly buried, how did he mummify? The researchers used forensic literature again. They learned about a mode of decomposition that may apply to Dakota.

The dinosaur carcass could have remained unburied for weeks or even months as animals, insects and microbes tore holes through the skin and ate away at the animal's internal organs. The holes in the skin would have allowed gasses and fluids from the dinosaur's corpse to escape and cause the skin to dry out.

According to the study, at that point the carcass would have donned a "deflated appearance, with skin and associated structures draped closely over the underlying bone." The deflated dino would have been buried and fossilized at a later date, and would look like the Dakota specimen it is today.

It is fairly predictable in the forensic literature. It wasn't something that had been looked at in the context of dinosaur mummies.

It is reasonable to think that most of the dinosaur mummies are formed through desiccation and deflation. The team wrote in the study that some dinosaurs may have formed through being submerged in water with little oxygen present. The lack of oxygen in the deep water would slow the decomposition process and allow mummification to take place.

The researchers are confident that they know what happened to Dakota after he died, but they don't know what happened after he was buried. To analyze more dinosaur mummies that formed in the same way Dakota did, the team wants to study which chemical reactions allow dinosaur skin to fossilize.

There is a question as to why so much of the dinosaur skin is duck-billed. He said that if it was just about scavengers leaving skin behind on abundant herbivores, then wouldn't we find a lot of ceratopsian and sauropod fossils with skin on them too? That is one of the questions to be explored in follow up studies.

Dakota can be seen at the North Dakota Heritage Center and State Museum while the research is going on. The rest of the specimen is being looked at. Fossil preparators have spent over 15,000 hours on Dakota so far, and they expect to spend thousands more with the mummy before they finish their work.

Live Science is a future company. All rights belong to the person. It may not be published, broadcast, or redistributed.