The University of Virginia School of Engineering and Applied Science.

At a rapid rate, the amount of energy used for computing is increasing. Information, communication and technology accounts for between 5% and 9% of the world's electricity use.

Up to 20% of the world's power generation could be needed by the year 2030. Engineers desperately need to flatten computing's energy demand curve because power grids are already under strain from weather-related events.

Jon Ihlefeld has a group of people doing their part. A material system that will allow the industry to co-locate computation and memory is being investigated.

Ihlefeld is an associate professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Virginia.

The computer chip needs energy to send a signal down the line when it wants to talk to memory. It takes more energy to travel the distance. The distance can be many centimeters.

In a perfect world, they would be in contact with each other.

The rest of the integrated circuit needs compatible memory materials. ferroelectrics are one class of materials that can be used for memory devices. ferroelectrics are not compatible with Silicon and do not perform well when made very small, a necessity for modern-day and future devices.

The researchers are playing a game together. Modern computation and communication can be made possible by the research of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering. Fabrication and Characterization of a range of materials is a research strength of the Charles L. Brown Department of electrical and computer engineering.

Hafnium oxide is used in the manufacture of cell phones and computers. hafnium oxide is not ferroelectric.

There is a tip of the cap to a person.

Over the last 11 years, it has been known that hafnium oxide's atoms can be manipulated to make ferroelectric phases. The crystallographic pattern of a ferroelectric material can be set in place when a hafnium oxide thin film is heated and cooled.

The formation of the ferroelectric phase has been the subject of a lot of discussion. A landmark study on how and why hafnium oxide forms into its useful ferroelectric phase was published by a graduate student at the University of Virginia.

Fields' paper shows how to stable a hafnium oxide-based thin film when it is sandwiched between a metal and an electronic device. When the top electrode is in place, more of the film is stable.

The community had a lot of explanations for why this is. The top electrode was thought to exert some kind of mechanical stress that prevented the hafnium oxide from stretching out. The research shows that the mechanical stress moves out of the plane.

This finding could affect the materials that are used in the manufacturing of transistors.

We now know why the top layer is so important. People who want to integrate computing and memory on a single chip will have to think about all the steps more carefully.

The conclusion of Fields' research is summarized in his paper. Fields demonstrated techniques to measure very thin films and mechanical stresses in the past.

Contributors in this collaborative research include a group of people from Brown University, a group of people from Oak Ridge National Lab, and a group of people from the University of Virginia.

Fields said that they wanted to provide data to back up their characterization of the material. I am happy that we were able to give the community more clarity about this. We can engineer the top layer to improve the effect, and maybe the bottom layer as well, since we know the top layer matters a lot. The ability to use a single experimental variable is a huge advantage for the field. Someone should ask and answer that question.

There is a mark on the spot.

A member of the Multifunctional Thin Film research group is a graduate student in materials science and engineering. What contributes to the stability of hafnium oxide's ferroelectric phase is something Jaszewski wants to understand.

The atomic make-up of hafnium oxide in its natural and ferroelectric phase is the focus of Jaszewski's research. Her study, Impact of Oxygen Content on Phase Constitution and Ferroelectric Behavior of Hafnium Oxide Thin Films Deposited by High-Power Magnetron Sputtering, was published in the October 2022.

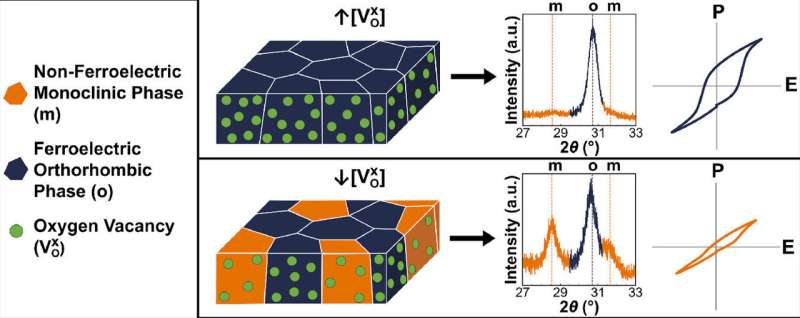

Hafnium oxide is made of hafnium and oxygen atoms. The ferroelectric phase can be helped by missing oxygen atoms in certain areas.

The ferroelectric phase can be stable with a number of oxygen vacancies, but not as many. There aren't many tools to make a definitive measurement of the concentration and location of oxygen vacancies.

The oxygen vacancies in the team's thin films were correlated with ferroelectric properties thanks to the work of Jaszewski. The ferroelectric phase requires more oxygen vacancies than was thought.

Oxygen vacancies concentrations can be calculated using x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. The undercount of oxygen vacancies is caused by factors beyond what users of this technique typically measure.

Oxygen vacancies might be one of the most important parameters to stabilizing the ferroelectric phase of the material. There is more research that needs to be done. She wants other research teams to use her method to measure oxygen vacancies.

Conventional wisdom says that the size of the crystal is what determines the stability of hafnium oxide. Three samples were made with the same grain size and concentration of oxygen. Oxygen vacancies concentration is more important than grain size according to her research.

Jaszewski was the first author of the paper, which was co-authored by members of the group. Jaszewski's research is funded by two organizations.

Jaszewski wants to understand how hafnium oxides respond to an electric field. Wake-up and fatigue is a phenomenon found in the Semiconductor industry.

The ferroelectric properties increase when you apply an electric field to it. The ferroelectric properties degrade as you apply the electric field.

There are diminishing returns when an electric field is first applied.

The ferroelectric properties degrade as you apply the field.

The study of where vacancies are located is needed to investigate how the oxygen atoms' choreography in the material contributes to wake-up and fatigue.

The studies explain how ferroelectric hafnium oxide works. We can engineer hafnium oxide thin films to be even better, based on the new findings. Semiconductor firms can learn how to prevent problems in the future by doing this fundamental research.

More information: Shelby S. Fields et al, Origin of Ferroelectric Phase Stabilization via the Clamping Effect in Ferroelectric Hafnium Zirconium Oxide Thin Films, Advanced Electronic Materials (2022). DOI: 10.1002/aelm.202200601The impact of oxygen content on phase constitution and ferroelectric behavior of hafnium oxide thin films deposited by high-power impulse magnetron sputtering is studied in a paper. The article is titled "Acquiat."

Journal information: Acta Materialia Provided by University of Virginia School of Engineering and Applied Science