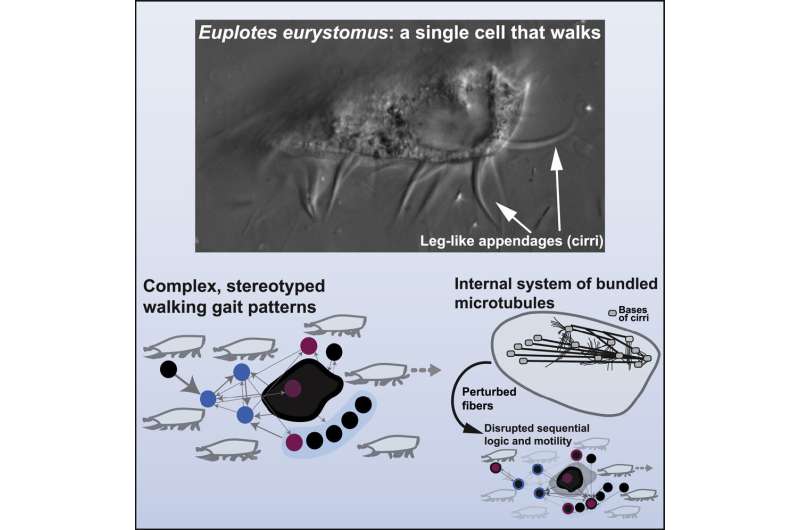

Brains are required to run, jump or hop. The single-celled protozoan Euplotes eurystomus uses a mechanical computer to coordinate its tiny legs in order to walk.

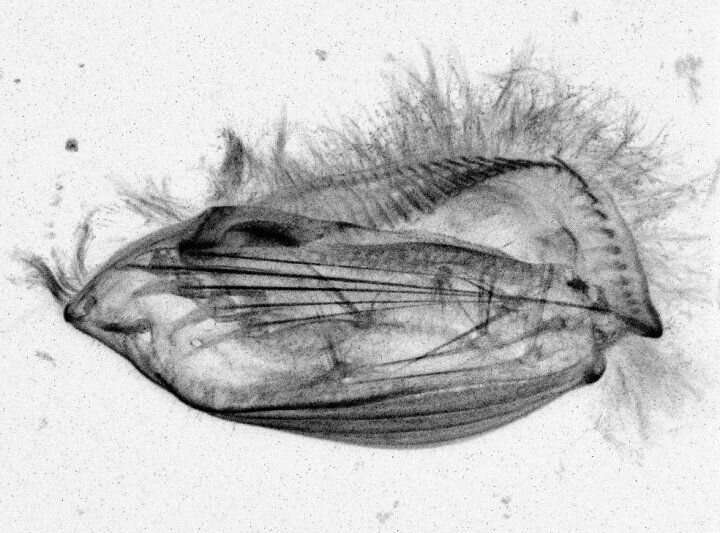

Each appendage of Euplotes is made of bundles of hair. The movement of the aquatic organisms becomes less productive when the internal connections are disrupted.

"Euplotes uses these connections to facilitate an elaborate walking motion, but my suspicion is when we dig into this more, we'll find that other cells use similar forms of computation to control more subtle processes," said Wallace Marshall.

Single-celled organisms in the water don't have legs or walk, they roll, swim or slither. When he saw Euplotes under his microscope, he thought he was looking at insects. He was interested in how the organisms coordinated their appendages without a brain or nervous system.

To understand this ability, the two men watched Euplotes cells in more detail, slowed down the videos of the walking cells, and labeled each leg.

The cells didn't walk like people, with their legs alternating, and they didn't have a good rhythm. The appendages followed certain patterns. The researchers were able to show that certain gait states were more likely to follow others.

The movements seemed to have sequential logic going on. We began to suspect that there was some sort of information processing going on.

There is a machine that makes microtubule.

Since the 1920s, scientists have known that Euplotes are projected from each appendage. The main component of a cell's scaffolding is composed of microtubules. When the microtubules were disrupted with a drug or a needle, the movements of Euplotes became more random and chaotic.

The researchers collaborated with computer scientists to model the motion. They came to the conclusion that strain and tension on the filaments could affect which states were possible. They said that the machinery resembles a sculpture designed by a Dutch artist.

Marshall said that internal machinery doesn't look like today's digital devices, but it does follow the principles of early mechanical computers.

He said that the system is like a rudimentary computer because the appendages are moving in a non-random way.

The researchers admit that more work needs to be done to understand how the Euplotes walk. Computational modeling and experiments show a completely new method for controlling a cell's internal state.

This is a fascinating biological phenomenon, but also could highlight more general computational processes in other types of cells.

More information: Ben T. Larson et al, A unicellular walker controlled by a microtubule-based finite-state machine, Current Biology (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.07.034 Journal information: Current Biology