An HIV-positive man became the first volunteer in a clinical trial aimed at using Crispr gene editing to cut the AIDS-causing virus out of his cells. He was given an IV bag that pumped the experimental treatment directly into his bloodstream. Gene-editing tools are to be carried to the man's cells to clear the viruses.

The volunteer will stop taking the drugs later this month in order to keep the disease at bay. The investigators will wait a year to find out if the virus comes back. The experiment will be considered a success if not. The CEO of Excision BioTherapeutics says they are trying to return the cell to a normal state.

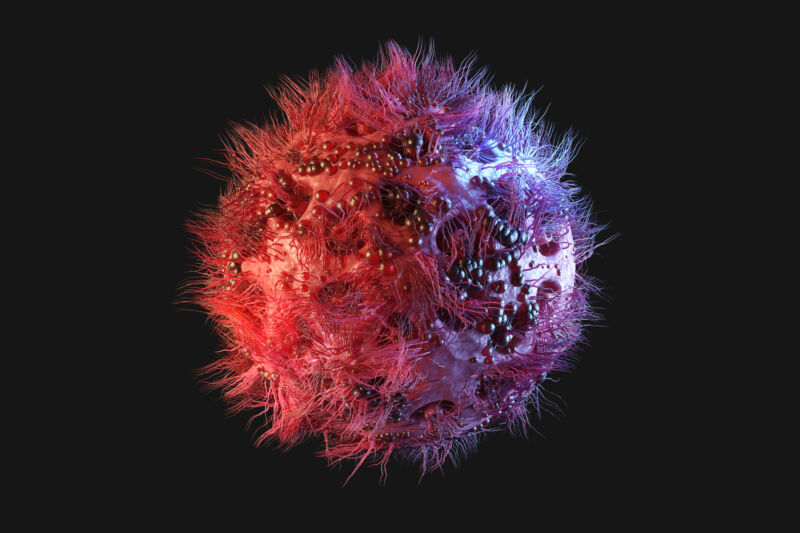

Jonathan Li, a physician at the Brigham and Women's Hospital and HIV researcher, says thatHIV is a tough foe to fight because it is able to insert itself into our own genes. It has been difficult to find a way to target these reservoirs without harming CD4 cells.

People with HIV have to take medication every day for the rest of their lives because they can't get the drugs to their cells. Excision hopes that Crispr will remove HIV.

Several studies are using Crispr to treat a number of conditions that arise from genetics. Scientists are using Crispr to modify their own cells. The gene-editing tool is being used in the HIV trial. Two regions in the HIV genome are important for the replication of the disease. Crispr is able to disrupt the process of reproduction by cutting out parts of the genomes.

Researchers at Temple University and the University of Nebraska used Crispr to remove HIV from rats and mice. macaques with SIV, the monkey version of HIV, were successfully removed from the Temple group.