The human immune system is similar to how a tiny marine invertebrate distinguishes its own cells.

The findings suggest that the building blocks of our immune system have evolved earlier than previously thought and could help improve understanding of transplant rejection.

Senior author Matthew Nictora said, "For decades, researchers have wondered if self-recognition in a marine creature called Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus was similar to the processes that control whether a piece of skin can be successfully transferred from one person to another." The study shows for the first time that a subgroup of the immunoglobulin super family is found in a distantly related animal.

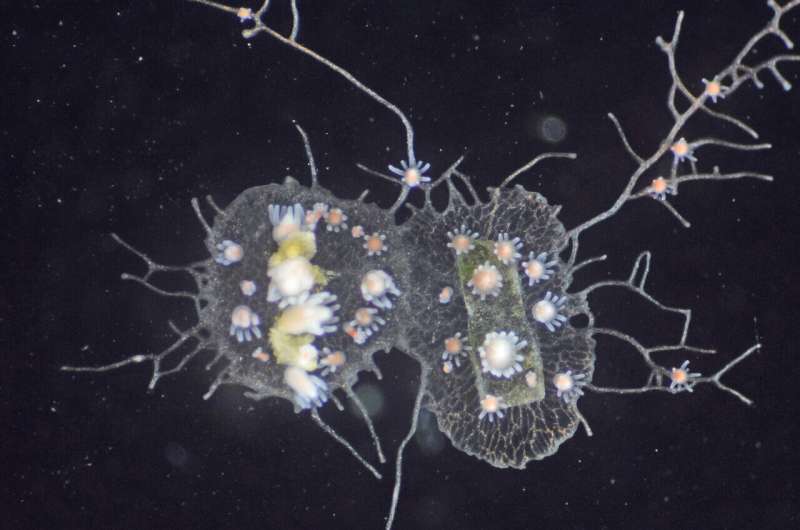

Jellyfish, corals, and sea anemones are part of the same group. The animals look a bit like inflatable tube men dancing outside of a car dealership. colonies are growing on the shells of the crabs.

"As colonies grow and compete for space on crab shells, they often bumping into each other," said the associate director of the Center for Evolutionary Biology and Medicine. Two colonies recognize each other as their own. The colonies fight if they identify each other as non-self.

The genes called Alr1 and Alr2 were identified by the group, but they predicted there was more to the story.

We had a flashlight on the two points, but we didn't know what else was there. We have been able to sequence the whole genome and illuminate the entire region around these genes. Alr1 and Alr2 are members of a large family of genes.

The researchers found 41 Alr genes that are likely to control self-recognition in Hydractinia.

The team wanted to know how the Alr genes work. The release of a tool called AlphaFold changed that, as it was nearly impossible to accurately predict the 3D structure of proteins based on a genes sequence.

In order to compare the structure of Alr and IgSF, the researchers used this tool. The V-set domain is a characteristic region of Ig SF.

The 'V' stands for variable. The immune system uses a variable sequence to recognize specific pathogens when a B or T cell becomes specialized to fight a particular pathogen.

The 3D structures in Alr were remarkably similar to V-set structures, even though they lacked telltale features.

He explained that these are V-set domain names. They're very strange.

The branch of the animal kingdom known as Bilateria was thought to be the location of V-set domain. mammals, insects, fish, mollusks and all others with right and left sides were part of this group.

V-set domains are part of a group that appeared earlier in the evolution of animals.

Several Alrproteins had signatures associated with immune signaling in other animals, a sign that the Alr complex is involved in self-recognition.

"We know a lot about the immune systems of mammals and other animals, but we don't know much about immunity in invertebrates." We think that a better understanding of immune signaling in organisms like Hydractinia could lead to alternative ways to manipulate those signaling pathways in patients with transplants.

The other authors who contributed to the study were Anh- Dao.

More information: Aidan L. Huene et al, A family of unusual immunoglobulin superfamily genes in an invertebrate histocompatibility complex, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2207374119 Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences