Mariko Oi is a news correspondent.

Imagine if you could put an ultra-thin, transparent solar sheet on your window to generate energy, not just from sunlight but also artificial lights in your room.

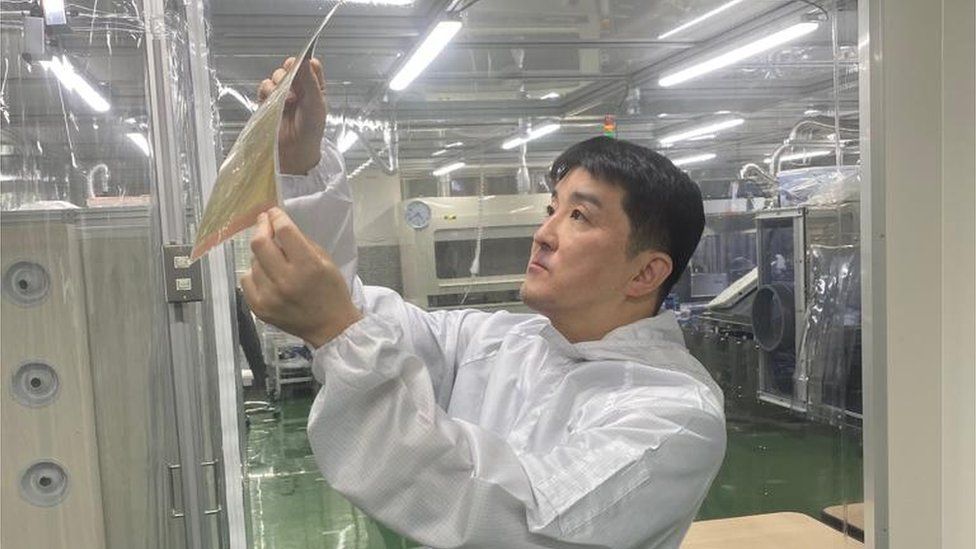

The Japanese start-up Enecoat Technologies is trying to develop a technology that is seen as the most promising next- generation solar cell.

The Kyoto-based firm hopes its product will produce the same amount of power as a regular solar panel.

The company hopes to market them in three to four years. It will take longer to make themdurable for any kind of weather conditions.

Deep tech is a term used to describe start-ups such as this. Small firms are merging high tech engineering innovation with scientific discovery. It is hoped that it will lead to the development oftransformational products.

Product launches in this sector take time. Private venture capital funds that lend money to entrepreneurs might be more cautious about investing in them.

Kyoto University is involved in that area. It's best known for producing more Nobel prize winners than any other university in Asia, but it also finances new start-ups through its two venture capital funds.

One of the beneficiaries is Enecoat Technologies, which has received over 3 million dollars. The Japanese government gave the university a $300 million fund to encourage entrepreneurship.

The Office of Society-Academia Collaboration for Innovation at Kyoto University is strong in hard science fields such as stem cell science.

It takes a long time and a lot of money to commercialise deep tech companies.

While a typical venture capital fund's investment period is 8 to 10 years, the university's scheme offers up to 20 years of support.

The number of start-ups created by Kyoto University students has more than doubled in the last seven years.

New Tech Economy explores how technological innovation will shape the new economy.

Kyoto University's growth rate is much higher than Tokyo University's.

The city of Kyoto has a reputation for producing start-ups. There are also Nintendo included. When it launched in 1889, it made playing cards.

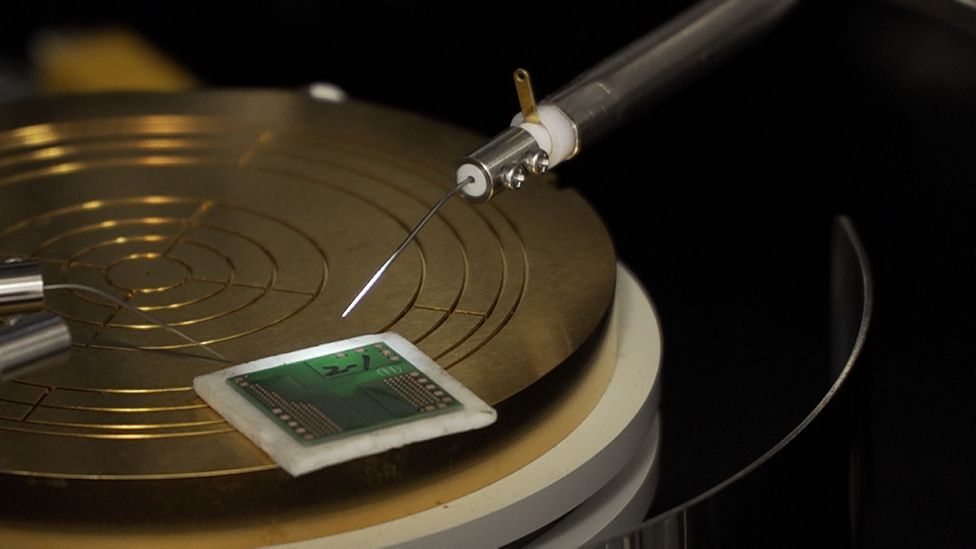

Flosfia is a deep-tech start-up that has been successful in the city. It makes semiconductors that use energy more efficiently so that they can extend the lifespan of the product.

The boss of Flosfia, a Kyoto University graduate, says that Kyoto is small and diverse. With so many researchers in a small community, anyone can access the information you need to start a business."

"But all the Kyoto-based companies' founders also say that, unlike firms in Tokyo, they don't have enough customers here in Kyoto."

It has been more than a decade since we started Flosfia because deep tech takes time.

Thirty years ago, Japan was a pioneer in the industry, but now it has less than 10% market share.

It will be a challenge for Flosfia to establish a significant presence in the highly competitive global Semiconductor industry as China and the US are trying to put their stamp on the market.

The House of Representatives passed a government act in July that commits a $280 billion support package for domestic chip production. The US would like to reduce its dependence on other countries.

Japanese producers have their own strengths, according to Mr Hitora. Japan is a good place to do basic research and work with new materials.

Flosfia has alliances with a lot of Taiwan's chip manufacturers.

"Semiconductors are needed globally, so some governments may try to intervene to ensure the supply for their home markets, but it takes a long time to produce them."

Stakeholders and businesses are needed to mass produce them. Our alliances with other companies are important.

Kyoto University's ability to patiently play the long game with firms such as Flosfia increases the hope that Japan will succeed.