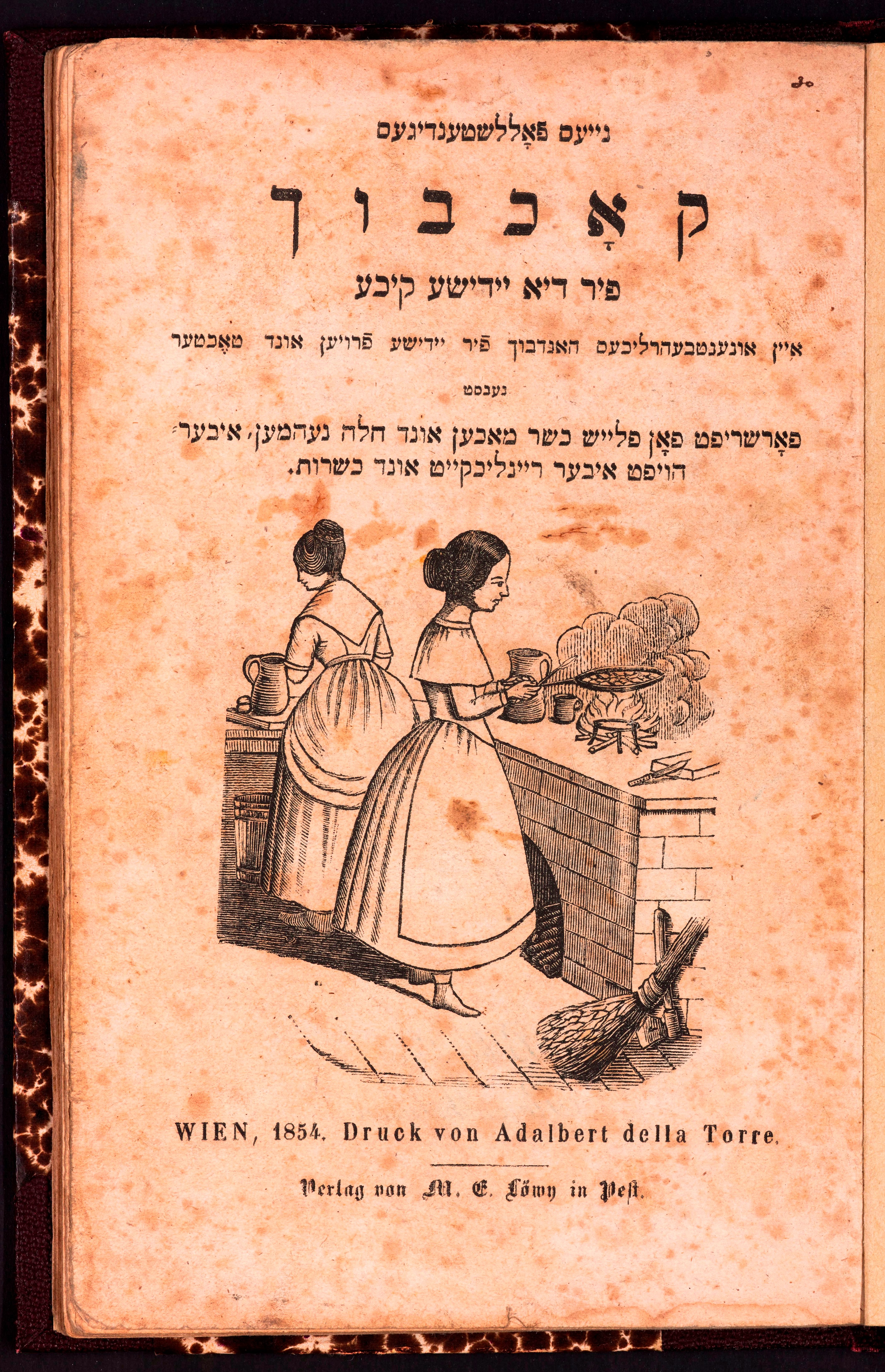

A few months ago, Andrs Koerner finally got to see the treasure he had been looking for. At the Hungarian Museum of Trade and Tourism, he held a 168-year-old book that had been thought to have gone missing. There was an illustration of a woman holding a pan over an open fire on the first page.

Before it ever had a Hebrew-lettered book, the pages ahead had a recipe. The book that historians thought was the first Hebrew-lettered cookbook was 40 years older than this one. The author of this year's Early Jewish Cookbooks says that it was a small sensation. After surviving the Nazi-occupied city's ghetto, Koerner grew up in a middle class neighborhood. A lifetime of connecting with his roots through food is part of his quest to find the book. While researching for his book Jewish Cuisine in Hungary, Koerner found a reference to a cookbook from 1854.

There wasn't a copy of the book left. A trail of clues led Koerner to a xeroxed copy of the book in a library at the Etvs Lrnd University in Hungary. A friend found the only surviving copy of the book in an online catalog of the University of Amsterdam. But Koerner only saw it from a distance.

Ayn unentberlikhes handbukh fir yidishe is the book.

THE GASTRO OBSCURA BOOKDo you like the world?

An eye-opening journey through the history, culture, and places of the culinary world. Order Now

It was a small scandal in the field.

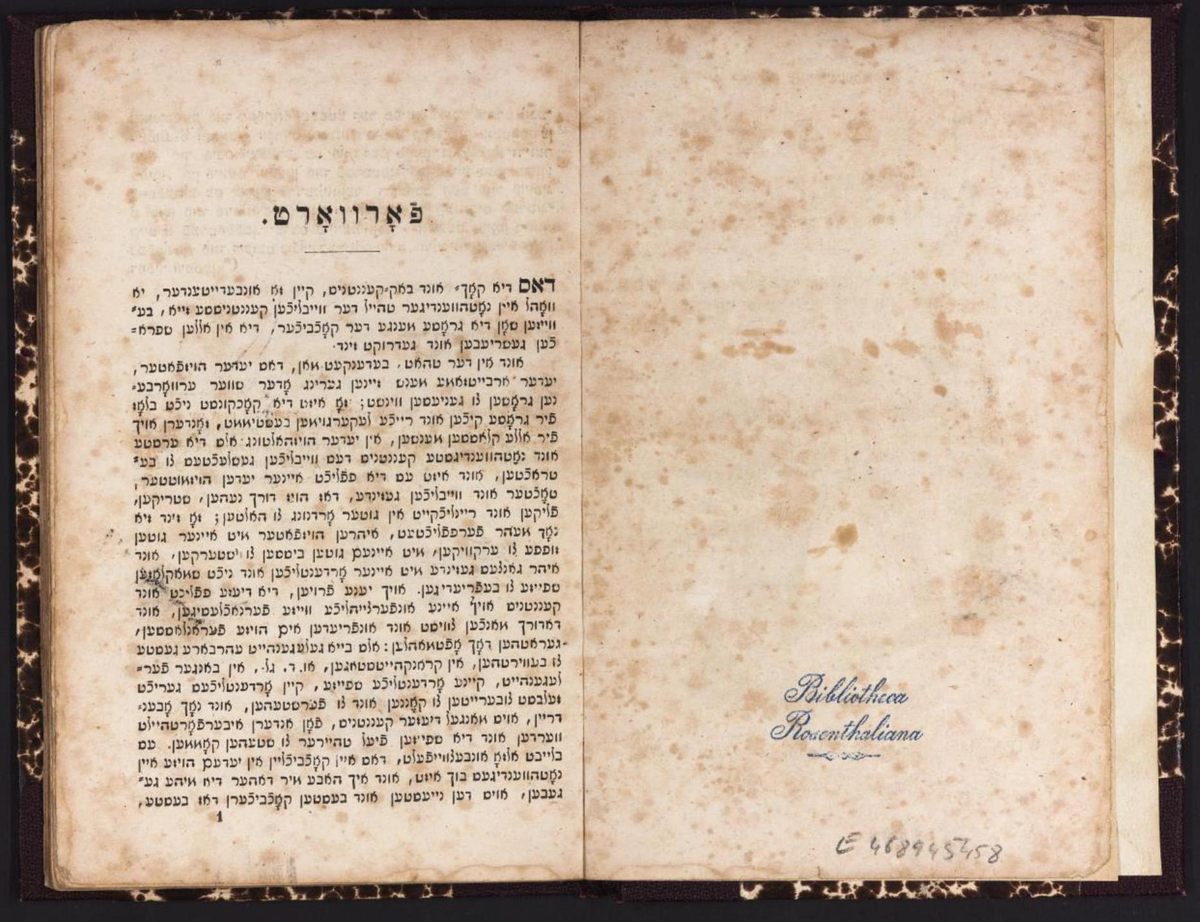

The book's Hebrew letters spelled out words in Yiddish, which was widely spoken by European Jews in the 1800s and was usually written in Hebrew characters. When Koerner asked her friend to translate the book into German, she was surprised to find it was written in Hebrew. The book was printed in Judeo-German, which is Hebrew-lettered German, in order to target the new Hungarian Jewish middle class.

Hungary was leaving a period during which Habsburg, Hungarian, and municipal leaders participated in barring Jews from Hungarian cities when Mrkus Lwy published his cookbook. They were separated from other Hungarians by law and their traditions.

In the late 19th century, some Jews left their cloistered lives and started speaking in Yiddish. The Hungarian Parliament granted Jews civil rights in the 1840s, including the right to own businesses, but they were not allowed to own property in Hungary.

“At least within scholarly circles, it was a small sensation.”

There was a large Jewish middle class in Hungary by the 19th century. Those were the people who bought Jewish books. The group of Jews who had settled in Hungary from Eastern Europe could not have bought Jewish cookbooks because they didn't have enough money.

The Haskalah, also known as the Jewish Enlightenment, prompted a wave of Jews to integrate into Hungary while retaining their religious traditions. The dress, education, and cuisine of their Christian counterparts were adopted by the Jews.

Kosher versions of fancy, Christian-Hungarian dishes such as "Hungarian Goulash Meat," "Root Vegetables in the Hungarian Way," and "Soup Made of Fresh Cherries" can be found in Lwy's 1854 book. The Hungarian-Style Apple Cake, which requires rolling out 25 loaves of dough and forming them into a layer cake, is exactly the type of dish that a middle-class Jewish woman in 1854 would have liked.

It was necessary to speak its dominant language and abandon Yiddish in order to integrate into Hungary's middle class. It was not just speaking German that was important. In 1870, only 75 percent of Jewish men and 58 percent of Jewish women could read and write in Hebrew. Publishers in Germany, Austria, and Hungary transliterated German words with letters that Jews recognized from reading Hebrew and Yiddish books in order to address the discrepancy.

It is likely that the 1854 cookbook was marketed to women who wanted to speak German but didn't have time to read it. The vaybertaytsh was associated with women's Yiddish devotional books and was chosen to appeal to potential female customers.

L wy was late. The book was only published one time. The would-be customers had already read German text. Koerner thinks that this is the reason for the low number of copies of the book.

It is all the more precious because of its rarity. A friend of Koerner told him about a physical copy of Early Jewish Cookbooks that was going to be auctioned off. Hungary's National Library bought it. The book is currently on display at the Hungarian Museum of Trade and Tourism as part of an exhibit on Hungarian-Jewish cuisine.

It was emotional when Koerner was able to look at a physical copy of the book he had been looking for. It was great. He says it was joyful. If I wanted to brag, I was a bit proud of it.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.