The closest flyby of Jupiter's icy moon, Europa, will be performed by NASA's Juno probe on September 29th.

One of the most intriguing places in the solar system to search for extraterrestrial life and one of the top priorities for Astrobiologists is the moon of Europa. It will teach us more about the moon's icy surface, such as how thick it is, and whether there are any pockets of liquid water on the surface.

Jupiter's atmosphere has been studied from the heights of its ruddy brown cloud top to the depths of the lower cloud layers hundreds of miles down, as well as learning about the gas giant's powerful magnetic field.

NASA granted the extension of the mission to study some of Jupiter's moons. The largest moon in the solar system is located at 3,272 miles across. Next, it will be Europa's turn, with Juno set to hurtle past the moon at just 220 miles above the ground. A small portion of the moon will be seen by Juno. The wide field of view that the cameras have allows them to see more of the landscape than a normal camera can.

The first photos from NASA's epic flyby of Jupiter's biggest moon look amazing.

Scott Bolton, associate vice president of the Southwest Research Institute Space Science and Engineering Division and principal investigator for the Juno mission, told Space.com that the work at Jupiter is considered a "scouting mission" for the upcoming NASA mission. We're going to be doing a lot of science at the place.

The MWR will be a key part of that science. The instrument we invented to see beneath the clouds of Jupiter is a new kind of instrument. The same instrument can be applied to an icy satellite.

The thermal emission can be detected from below the ice. It depends on the level of impurities in the ice. The deeper into the ice the MWR will be able to see.

The MWR instrument confirmed that the giant moon's ice was very thick when it was directed by Juno.

At some points on the moon, the story may be different. One day scientists hope to drill through the ice into the moon's ocean. The ice crust is expected to be around 30 km deep in most areas, but it may be thinner in some areas.

There are new views of Jupiter's icy moonEuropa.

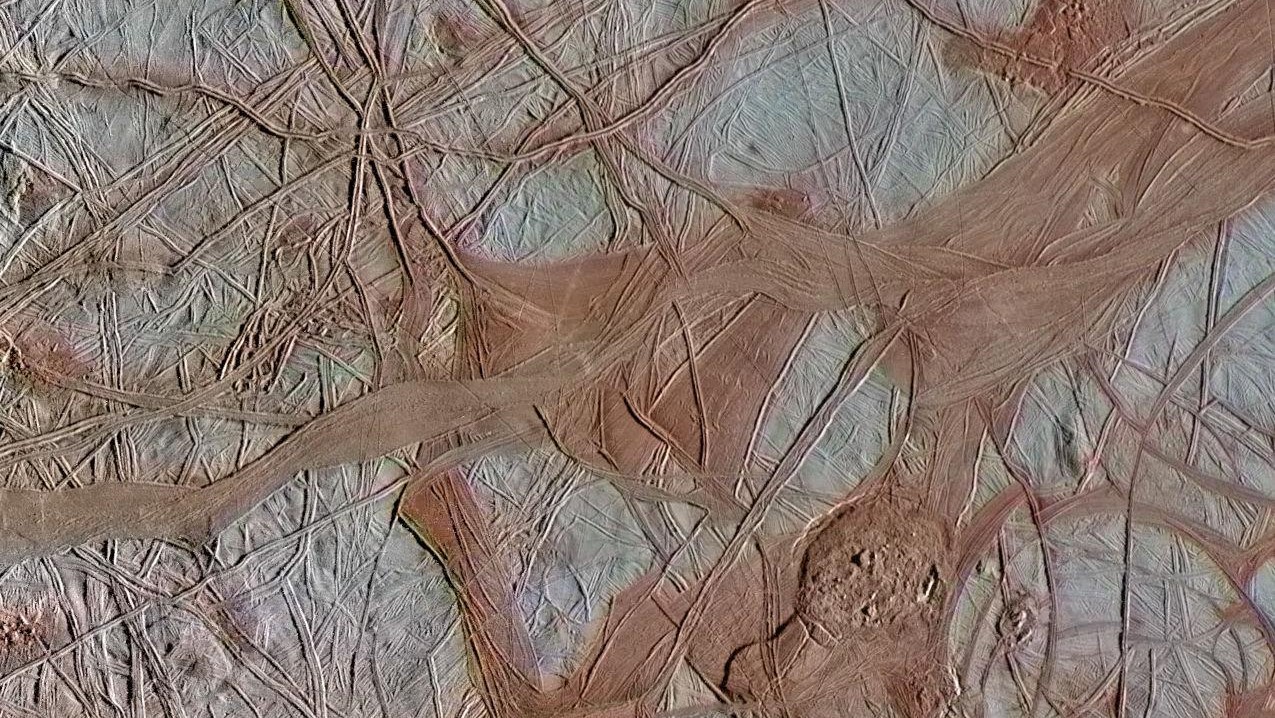

Some of the moon's surface is stained by material that seems to have welled up from below. The composition of this material will be determined by the composition of the camera and analyzer.

One theory is that there can be pockets of water in the subsurface, either through liquid convectively rising up through the ice shell, or by the ice in the shell melting. If there are any pockets of water close to the surface, the MWR should be able to tell.

We were focused on Jupiter and didn't think about going near the icy satellites. "Now that we're looking at the moons for our extended mission, it has become obvious that the microwave radiometer works incredibly nicely at icy bodies and gas giants, so I believe it will become a mainstream workhorse in future planetary exploration."

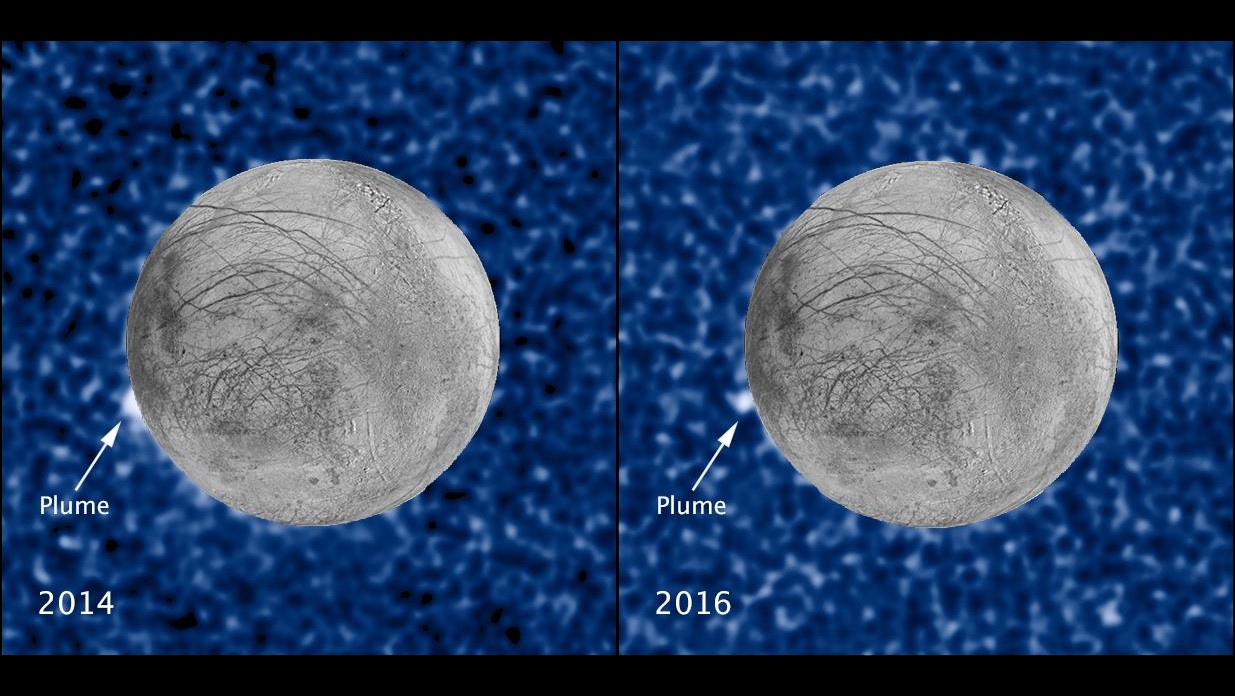

There is evidence for geysers of water that climb high above the surface and into space. The Hubble Space Telescope was able to see the possible silhouette of the clouds of hydrogen and oxygen. Scientists looked at the data from Galileo and found that there were small changes in Jupiter's magnetosphere that may have been caused by charged particles in the Jupiter's magnetic field.

Scientists were able to detect enough water vapor to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool in just minutes. Scientists haven't been able to confirm the existence of water geysers as of yet.

During its flyby, could it possibly detect a geyser? He said it was a long shot. We have to get lucky and have them go off while we fly past, and they have to be in a place that we just happen to be looking at.

The geological feature on the surface that's emitting water vapor is similar to the " tiger stripes" on the Enceladus moon. The navigation cameras of Juno will look for icy particles drifting down to the surface.

Previous missions focused on the central regions of the moons. This is the only chance that the spacecraft will be able to see the planet.

"What's happening is that Jupiter's gravity is twisting the trajectory of Juno's flight," he said. The point at which we cross the equator is moving inward as we approach Jupiter.

In the summer of 2021, Jupiter's equator was crossed by Juno. It is crossing Jupiter's equator at a distance of over half a million miles. There will be two close flybys of Io in February and December of 2024, as well as crossing Jupiter's equator at the distance of its volcano.

When the extended mission ends, scientists will have to make a decision about whether the mission should continue or end.

If the spaceship is healthy, NASA might entertain another extension.

Radiation is the main issue. Every time it reaches perijove, the closest point to Jupiter, it gets a large dose of radiation from the charged particles trapped in Jupiter's powerful magnetosphere. "Our shields will no longer hold, to use Star Trek language, and the radiation will start to harm Juno's electronics."

It will not be the last mission to visit Jupiter's icy moons, even if it is the only one. The mission is scheduled to launch in October of 2024 and reach Jupiter in April of 2030. More than 50 close flybys of the moon will be performed by the Europa Clipper, followed by the search for pockets of liquid water that could support life. In July 2031, the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy moons Explorer will make its way to Jupiter.

The 21st CenturySETI has a verified account. We encourage you to follow us on social networking sites.