The positions of the Moon's poles have changed as a result of asteroids hitting it.

The Moon's body has been rolling due to the impact of asteroids over the past 4 billion years. Any ice tucked away in craters at the lunar poles is not likely to have been affected by this shift. Future lunar exploration can go on as planned.

"Based on the Moon's cratering history, polar wander appears to have been moderate enough for water near the poles to have remained in the shadows and enjoyed stable conditions over billions of years," says Vishnu Viswanathan.

The history of the Moon is written in its craters. The scars of impacts that have taken place over billions of years are visible in the largest natural satellite on the planet. The distribution of mass on the moon has changed because of these impacts.

Each time a chunk of space rock slams into the lunar surface, it changes the moon's gravity. This can change the way an object moves over time.

Lower-mass holes are brought closer to the poles by the empty spaces excavated by asteroids. The mass concentration is closer to the equator. Think of the way a hammer thrower spins to hit the hammer harder.

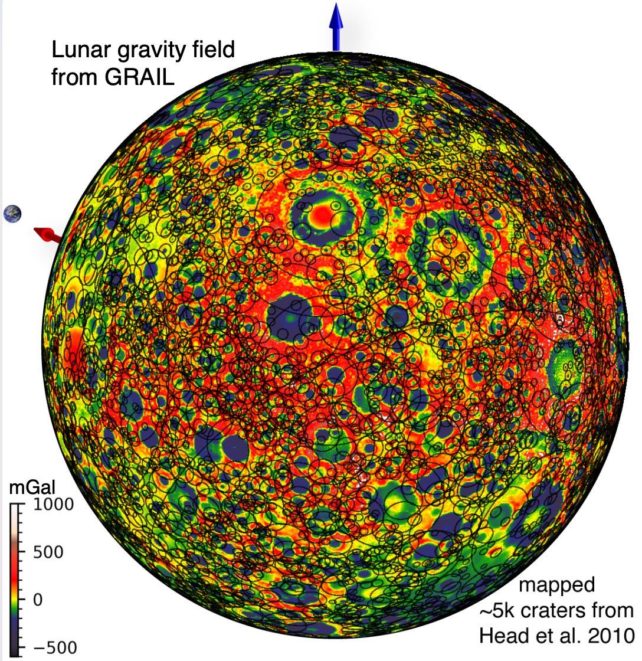

Thanks to a NASA mission called GRAIL, an extremely detailed map of the Moon's gravity field, the effect of the craters can be seen. David Smith of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was inspired by this.

Smith says that you can see the craters in the gravity field data if you look at the moon. I wondered if I could just take one of the craters and suck it out.

The team wanted to eliminate craters larger than 12 miles across. They mapped the craters and basins to the data from GRAIL and then erased them.

They worked manually before giving the job to computers.

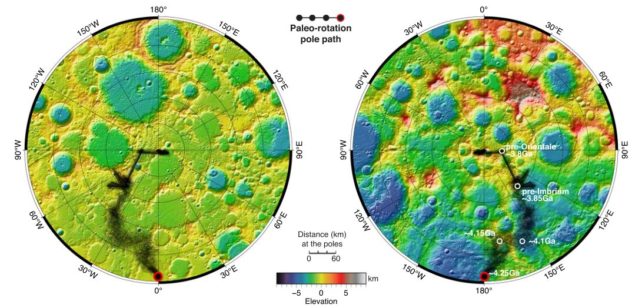

Each crater's effect was small. The lunar poles crept back towards the position they were in billions of years ago when there were many of them. The impact zone of the South Pole-Aitken Basin was almost equal to that of the small craters.

The people assumed that small craters were insignificant. They have a large effect.

The effect could have pushed the polar regions of the Moon into places where the craters are illuminated by the sun. If this were to happen, any frozen volatiles sheltered in the shadowed crater floors would sublimate and leave less ice as an enduring record. NASA's upcoming Artemis mission would have implications since scientists want to investigate the poles to find these icy patches.

The team showed that the effect was small. There is still more to be done.

The final result of the analysis is interesting, but not the whole story. There are a lot of craters on the moon that are outside the parameters the team included. The moon has not always been as quiet as it is now. Over time, volcanic activity could have changed its gravity.

Previous work only looked at craters larger than 200 kilometers. The team says that this work shows that there is more to life than meets the eye.

There are a few things that we haven't taken into account yet, but one thing we wanted to point out is those small craters that people have been neglecting.

The research has appeared in a journal.