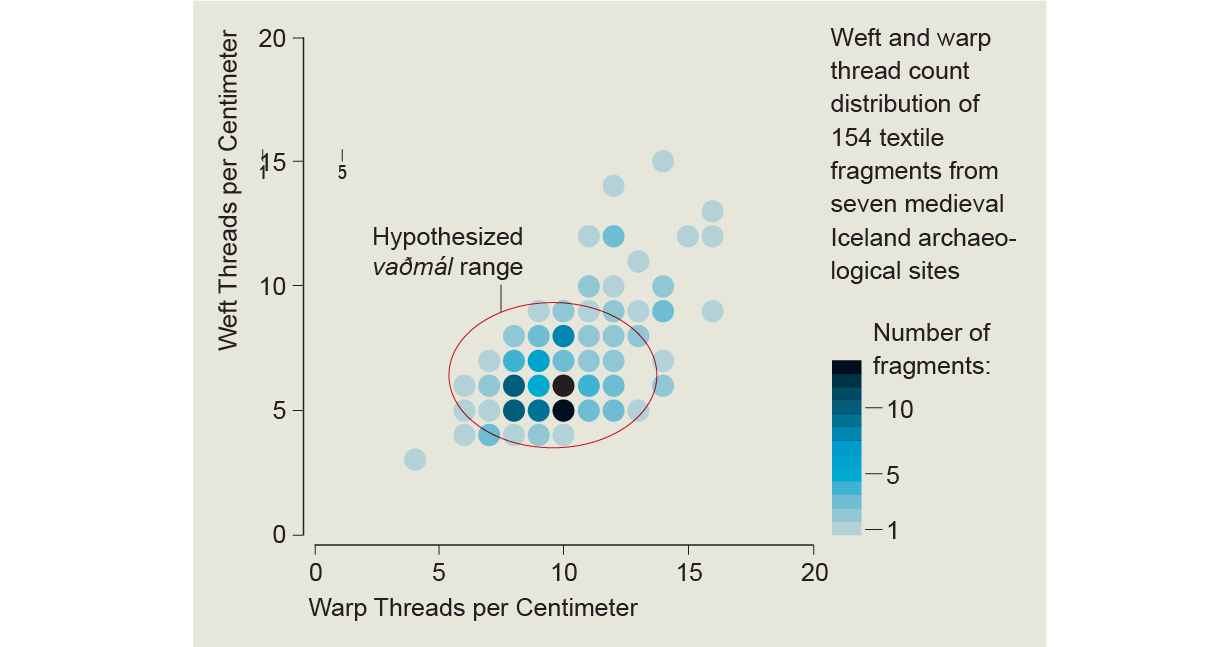

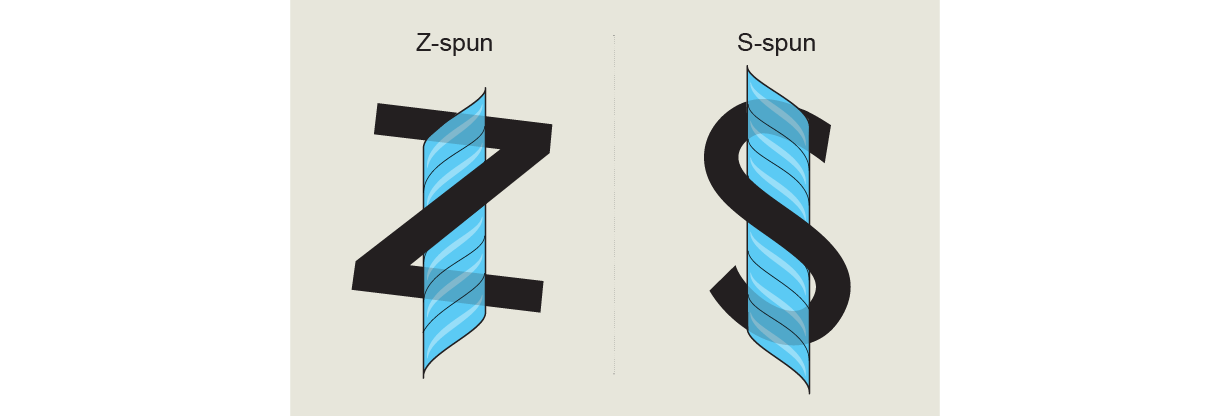

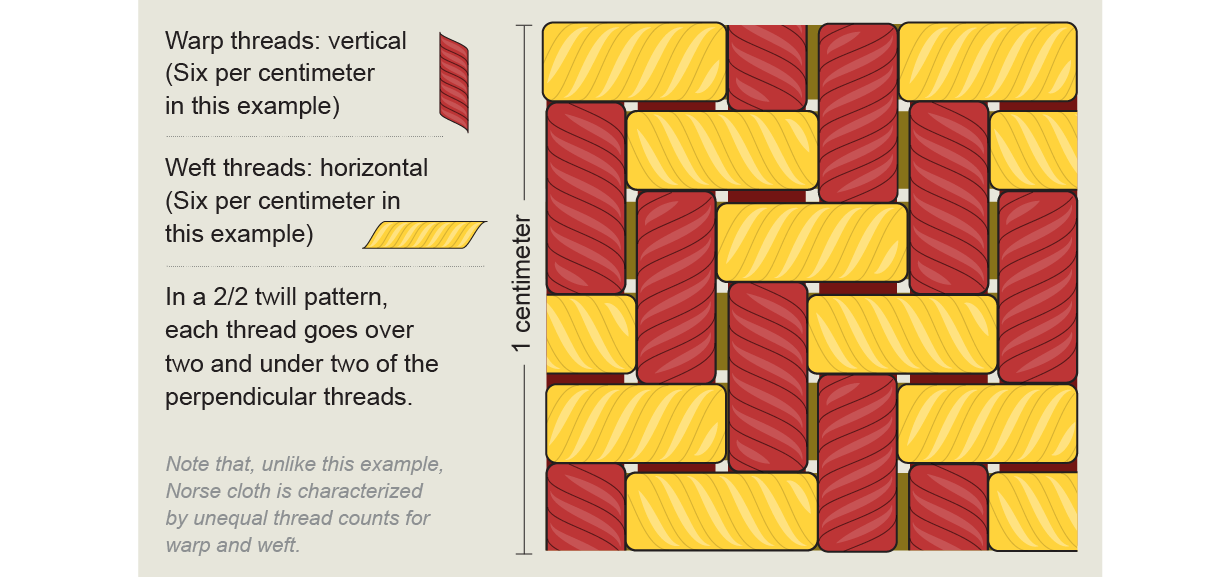

She is a veteran journalist with a specialty in social sciences. She is the author of Love after 50: How to find it, enjoy it, and keep it. The credit is given to Nick. There is a representation problem. The activities of men have been the focus of most of the time that scholars have been looking at the human past. There are two reasons for this. The types of artifacts that tend to preserve well are made of materials such as stone or metal and are associated with behaviors stereotypically linked to men. Early archaeologists were more interested in men's work than in women's. Our understanding of past cultures isn't complete. In recent years archaeologists have sought to fill that gap in our knowledge by taking a closer look at textiles, which had been dismissed as trivial. Cloth rarely lasts the centuries because it's easy to break down. It has a lot of information about the people who made it. Michle Hayeur Smith, an anthropologist at Brown University, has been at the forefront of efforts to glean insights from ancient cloth, combing archaeological sites and museum collections for textiles that could illuminate the lives of women. Her work shows that the Vikings wouldn't have expanded their world without the work of weaving. There were rows of metal shelving bursting with boxes and bags of dirt-covered cloth when Hayeur Smith studied early North Atlantic textiles. The museum's collection of remains from the Viking Age and later periods was inspected by her in 2009. She said it was thousands of fragments. They were barely looked at by anyone. Her mother collected fabrics from all over the world. Hayeur Smith attended fashion school in Paris. She was aware that the way people dressed in the past could show a lot about a lost culture. She studied Viking women's dress and ornament from artifacts found in burial sites as a PhD student. Hayeur Smith decided to uncover the lives of the ordinary women who stood weaving at their looms after seeing the wealth of textile remnants in the museum's store room. Since then, she has been analyzing textiles from all over the world, beginning with the Viking settlement of Iceland. She's poring over thousands of soil-encrusted fragments with information about the women who made the fabric Among the first to prove the importance of cloth and women in ancient societies was her study of the museum's neglected collection of brown scraps. The textiles are trivial. Hayeur Smith, blond hair spilling to her waist, speaking in a voice ringing with conviction, spoke in my interview with her. Building houses and power struggles were just as important as textiles and what women made. The basis of the North Atlantic economy was based on women and their cloth. Vikings are seen through the eyes of the era. They were seen as weak and subservient in the 50's. They were sexually abused in the 70s. They are depicted as shield-maidens or warriors in some shows. The real lives of Viking women were not known to science until Hayeur Smith began her work. The basic outline of Viking society is said to have come from the Icelandic sagas. More than 300 years have passed since the events they describe. The authors were Christianized and wrote about their ancestors. Women from the Vikings have long been stereotyped as doing mostly domestic chores, such as child rearing, cooking, weaving and making clothing. Archaeological evidence shows that they were weavers. Hayeur Smith says that women ran the farms and engaged in trade while their husbands were away. McGovern says there's some truth to the idea that women's work isn't as interesting. McGovern entered archaeology in the 70s. He remembers that most of the time it was old white guys. He says the field has changed since then, with more women and diversity. Archaeologists say traditional views of women still affect their interpretations of evidence. A Viking expert who studies gender in the archaeological record says that she sees how the meaning of artifacts is warped by preconceptions. The grave filled with a warrior's weapons at the Viking site of Birka in Sweden was thought to be a man's final resting place until it was proven to be a woman's. Sanmark is an authority on Vikings and medieval archaeology. She says a man buried with scales is seen as a merchant but a woman buried with scales is not. Hayeur Smith wanted to find North Atlantic women who were working. It was men who were analyzing this from the perspective of men and medieval law codes written by men. They didn't look at the actual stuff made by women. She didn't start her analysis completely from the beginning. One of the earliest studies of textiles was done by the late Elsa Gujnsson. Hayeur Smith says that Gujnsson was able to study a few pieces of fabric from the mountain of artifacts. Technical details such as thread counts, weave types, fleece varieties, and tools used to make them understand the techniques of weaving were the main focus of Gujnsson's work. Hayeur Smith wanted to uncover the lives of the women who created the cloth in order to create what she calls a "Social Archaeology" of the culture. She focused on the ordinary woolen fabric made by ordinary women who left no elaborate graves on their farms. The textiles they wove are their only memorial. A recording of Hayeur Smith demonstrating the Vikings' weaving style at an event at the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology at Brown in 2020 can be found on the internet. A wood horizontal bar resting on two vertical ones holds the separate vertical warp threads that are weighed down by volcanic stones. She uses a heddle rod to separate the warp threads from the horizontal weft thread. By changing the number of warp threads, weavers were able to create a common pattern. Kevin Smith, Hayeur Smith's husband, said that the loom would have been set up in a dyngja, a weaving hut. The pit houses are usually dug down 1.5 to three feet deep, with turf walls above the pit and wood walls that would have been high enough for people to stand and work. The small buildings would have provided an intimate space fitting a loom and perhaps three women, spinning, weaving and sharing stories. Hayeur Smith visited the museum's basement laboratory several times in 2010 to look at samples under a microscope and count warp and weft threads. Hayeur Smith entered her data and took small samples for further analysis and testing. She studied fabric remains from museums in several countries. She measured the diameter of the cloth and the size of the remnants. She kept a record of the age, site of origin and manufacturing details for each specimen. Hayeur Smith had an eureka moment between the first and second year of this job. She showed me on the video call how to use a graph and circled icons. I saw this pattern after checking more than one site. The textiles of the viking age were colorful and varied, but in medieval times there was a complete shift into standardized cloth. From the 12th to the 17th century, every textile from every site fell into a tight range of four to 15 warp threads. In the 11th century the spin direction of the yarn shifted from Z-spun to S-spun. The vaml is the specification for legal cloth. She claims that women were making money. It was based on Norway's system. The equivalent value in silver was used to assign a value to certain commodities. Homespun woolen cloth became more important as a form of exchange in the end of the Viking Age than it was in the beginning. The shift may have been caused by a shortage of silver after the Vikings stopped raiding, according to scholars. Hayeur Smith writes in her book The Valkyries' Loom: The Archaeology of Cloth Production and Female Power in the North Atlantic that the cloth was regulated as an exchange good in and of itself. She explains that the name vaml is a combination of the Old Norse words va and ml. From the 1100s into the 17th century, it was used as a measure and medium of exchange in many of the legal texts in the country. The vaml was made by women. They were making a lot of it as both a unit of currency and a commodity. Vaml can be used to pay taxes, but it can also be used to make clothes and other items. It was in demand in England, where it produced its own luxury fabrics but needed a lot of it to clothe peasants, the poor and soldiers. Work done at home is considered domestic and lesser because it doesn't produce money. Home was where work was done. Hayeur Smith points out that vaml was a major income generator. The medieval law books defined vaml in a way that scholars knew about. The women weaving it are not mentioned in the legal texts. The cloth remains were not checked to make sure they were in line with the legal texts. She looked at the legal texts in conjunction with her textile analysis. She was able to confirm that the cloth was woven with four to 15 warp threads per centimeters. The cloth was supposed to measure two ells in width and six ells in length. The cloth can be assumed to be larger based on the fragments she analyzed. It was equal to the weight of silver. Hayeur Smith says that everyone assumed the economy was a man's thing. The decisions were made by the women. She thinks that women and men collaborated to create the specifications. Hayeur Smith admits it is difficult to know what they were thinking. Every able-bodied female in a household would have been involved in the process. She says that they may have had control of a lot of the narrative. She says that it's not the men sitting there writing books. Evidence from poetic and mythological sources, including the Icelandic sagas, give clues to deep-seeded attitudes toward women in the Viking Age and beyond. According to Karen Bek-Pedersen, an expert on female aspects of Viking religion, the power of women is shown in the Darraarlj from the Njls saga. A soldier at the dawn of a battle has a vision in which he looks into a dyngja and sees a group of female warriors. The men's viscera is used as part and thread in the weaving. They describe the defeat to come as they weave. She said this. The fabric is warped

with men's intestines

and firmly weighted

with men's heads;

bloodstained spears serve

as heddle rods,

the shed is ironclad,

and pegged with arrows.

With our swords we must strike

this fabric of victory

Hidden Figures

Written in Cloth

Cloth Currency

Looming Taboos

According to Bek-Pedersen, poems from the sagas probably predated the sagas themselves. Filled with metaphor, alliteration, rhythm and rhyme, they are hard to alter and easy to remember, making them likely to have been passed down from generation to generation.

The dyngja can be seen as a space with a feminine energy that surpasses the abilities of ordinary human women. She says that in the literary canon men who hang out there and gossip with the women are portrayed as villains and end up going to jail.

Hayeur Smith's appraisal of women's power in cloth-making is affected by the fact that the dyngja was a space man. Men were afraid that if they entered, they would lose their manhood. The main living area of the longhouse had looms. With the taboos about this women's craft most likely, weaving would have been done in a seperate area or room. The taboos became a key factor in women's power as their cloth became a major driver of the economy.

McGovern and Hayeur Smith met in a Chinese restaurant in New York in 2011. McGovern brought some bones from an excavation he and his team had done a few years before. He was happy to give the textile bits away because he was curious about what she could learn from them. He thought about good luck when he handed them over.

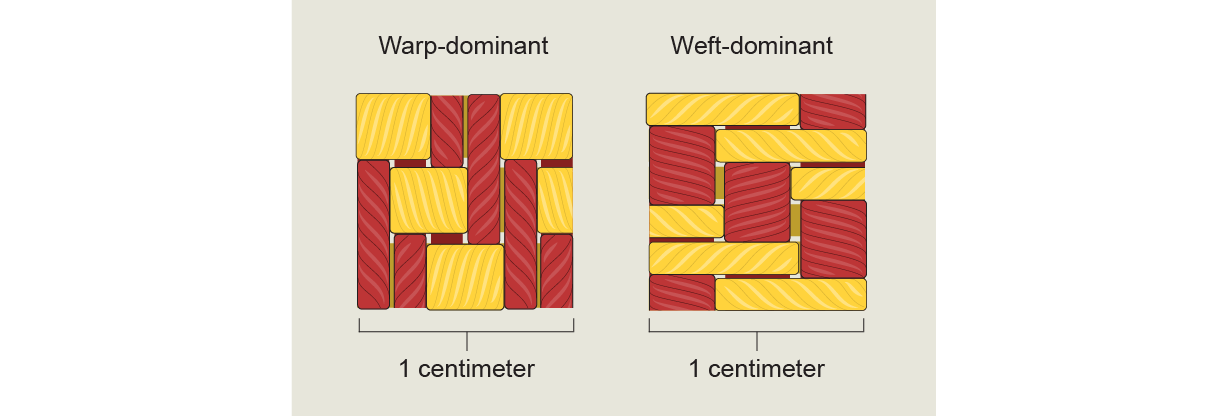

Hayeur Smith was looking for the reason why the cloth made by the women of Greenland differed from the cloth made by the women of Iceland. The entire territory of Greenland was settled by the people of Iceland. They were followers of a man called the Red. The warp-dominant fabric of the Icelanders was the same as the cloth of the Greenlanders.

The late Else stergrd proposed an explanation for the shift. Hayeur Smith held up a tattered copy of stergrd's 2004 book Woven into the Earth and said that she thought it was a response to the Little Ice Age. The first dramatic drop in temperatures began in 1340 and continued through the 15th century when the colonies disappeared.

Hayeur Smith wanted to find out if stergrd's hypothesis was true. She says McGovern's specimen wasphenomenal. Excavated under controlled conditions from a series of layers of remains, they were filled with information about the changes that occurred. Hayeur Smith collaborated with McGovern's student Konrad Smiarowski to review their excavation plan. The weft-dominant cloth appeared later in the day.

Hayeur Smith was able to correlate the ratio of weft to warp threads in each sample using published records of climate data. As stergrd had predicted, weft-dominant cloth increased in temperature. She says it was perfect with the climate data.

Hayeur Smith said that it was just one site. She had to collect remains from all over the island to prove that women were adapting their weavings to the changing climate.

Hayeur Smith's pursuit of women in textiles brought her to an old trading house in Nuuk Harbor, where she could watch the ocean. The building was built by Hans Egede in the 18th century. She was the only one who did research there. She felt a sense of uneasiness when the storms hit the house at night. She learned from locals that the abode was thought to be haunted.

She laughs at her fears as she recounts them from her home office in Rhode Island, which is filled with art and portraits of her French Canadian and American great-grandfathers. Hayeur Smith went to the Nuuk museum and the National Museum ofDenmark to inspect some 700 cloth samples from archaeological sites. She went back to Nuuk to look at more samples. She was able to correlate the years of climate change with the evolution of weft-dominant cloth due to all the dating she did. She confirms that it was climate change.

Hayeur Smith points to a graph in her book. That is the climate data. An arrow goes down to 1320. She says that's when you see dominant cloth. Between 1300 and 1362.

The weaving ofdominant textiles intensify after those dates. She wrote in The Valkyries' Loom that it became the most common textile produced in the island. It was almost certainly a response by the local weavers to the cold weather. She had found her women. She exclaimed, "I could see in the piece of cloth, the deliberate decision-making that women were doing, like it's getting cold, let's change the way we weave our cloth." It's rare to see people's direct actions in the past.

Natural, political and economic forces stripped the power of the women who made the all- important cloth from them. Plague and political upheaval wreaked havoc on the Kingdom of Norway by the time the Little Ice Age ended.

In 1603, the Danes imposed a royal monopoly on trading and required all imports and exports to go through their country. Although vaml was used as currency until the late 17th century, fish became the primary export from the 14th century onwards.

The English had male weaving guilds that produced fine cloths on foot-powered treadle looms. There are production workshops in locations around the country. Women were given spinning wheels that were more efficient than the traditional whorls used on the drop spindles. In response to a market demand for knitted exports, the Danes encouraged women to knit. They imported fabric from all over the world. It was possible for women to save their labor of weaving by buying it. Women were pushed out of the mainstream of weaving by the Danes.

Women continued to weave their homespun cloth on their farms despite Hayeur Smith's findings. Fragments of the textile have been found throughout the 17th and 18th century. She believes that it was used as a statement of national identity in the face of the new laws that were imposed by the Danes. She thinks it's as resistance.

The Danes were able to grow industrialization. Hayeur Smith says that nobody knew how to weave on the old looms. Women were worse off than men. She observes that once textiles could be made so much faster on machines than by hand, they came to be associated with things that werefrivolous or peripheral to our daily lives or of interest to women as their primary consumers. The Industrial Revolution sealed the fate of women as second class citizens and ensured that Western society would become so patriarchal.

Hayeur Smith is still interested in the stories only cloth can tell. Nobody is going to look at textiles the same way again after her publications.

The original title of this article was "The Power of Viking Women".

The article is titled "Scientificamerican1012-28."

View This IssueThe caveman has new clothes. The month of November 2000 was occupied by Kate Wong.

The Vanished Vikings were from the island. Zorich was in June of last year.

You can sign up for Scientific American's newsletters.

World-changing science is what you'll discover. We have articles by more than 150 winners of the prize.

Subscribe Now!