Hundreds of millions of years ago a creature gorged on a feast of prehistoric animals and then vomited up its meal. Paleontologists found the ancient upchuck and published their findings.

The remains of an animal's stomach contents were discovered during an excavation in southeastern Utah. Fossils dating to the late Jurassic period (164 million to 140 million years ago) can be found in this swath of rocks. Fossilized remains of plants and other organic matter are typically found in this section of the "Jurassic salad bar".

When a team that included researchers from the Utah Geological Survey stumbled upon a small pile of retched remains, they knew they had found something special.

John Foster, a curator with the Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum, told Live Science that the concentration of animal bones was striking. The bones we found weren't spread out among the rocks, but were concentrated to this one spot. We've never seen bones there before.

RECOMMENDED VIDEOS FOR YOU...

The largest dinosaur ever found in Europe may be in Portugal.

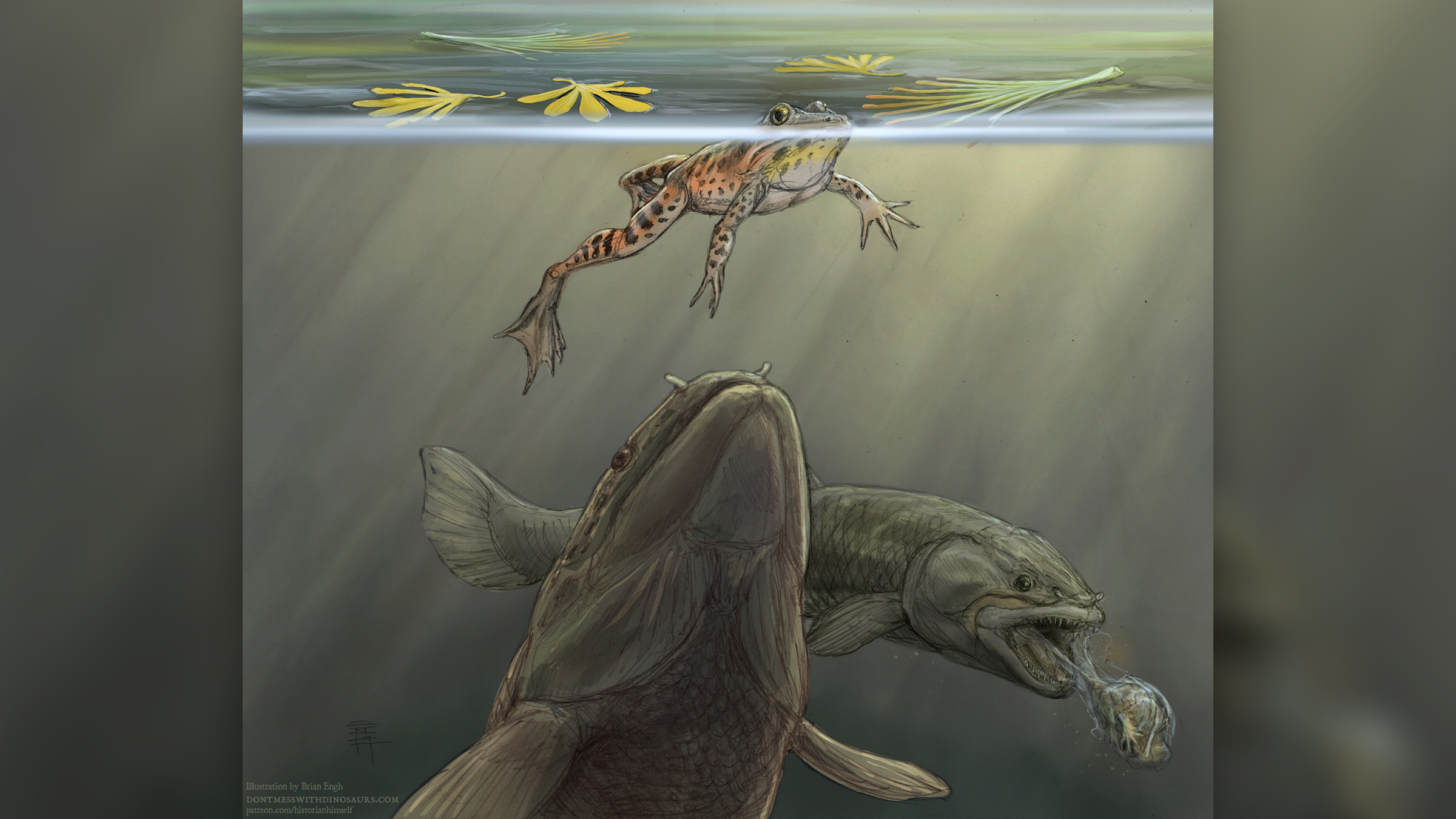

The team did not know they had found vomit from prehistoric times. The scientists thought they had found the bones of a single animal, until they realized that some of them were not from a single salamander. The material is mostly from a frog and salamander. We began to suspect that what we were seeing was vomited out by a predator.

There are bones from a frog and a salamander among the remains. A matrix of soft tissues and bone fragments were found along with each other. Researchers determined that this is a regurgitalite because it isn't completely digested.

Foster said that this is the first instance of one at the Morrison Formation that has been recorded. There isn't a way to know which species of animal lost its lunch millions of years ago, or why it upchucked in the first place.

Foster said that there's more to this thing than just the bones of the animals. We can rule out things by doing a chemical analysis.

It was originally published on Live Science