There is a long-standing assumption about natural evolution that has been confirmed by a series of experiments. Proponents of intelligent design have argued that naturally occurring changes will only damage or destroy an animal and can't lead to useful new features.

Changes in the number and length of the stickleback's major defensive spine were discovered by the researchers. Anti-evolutionists argue that major changes will always leave animals unable to survive in the wild.

Changes in the regulation of the HOX genes control the development of major body structures during development, according to David Kingsley, professor of developmental biology. New features that help fish thrive in natural environments were shown to be caused by the mutations in this genes. If you play with master regulators, you're only going to make a bad monster, according to our findings.

The senior author of the research is an HHMI investigator and a professor. Wucherpfennig is a graduate student.

Evolution can happen in a variety of ways. An animal that is more suited to its environment is the result of aggressive evolution. Cave fish that have lost their eyes after generations in darkness and early humans who shed their hairy suit of ape relatives are examples of neutral changes.

There is a chance.

In contrast, progressive evolution happens when organisms are able to out compete their peers. Such changes are akin to rolling the genetic dice and hoping for the best. Changes are less risky if they are smaller and gradual. Imagine if one day you had to leave your apartment because of a big structural change. Are you more likely to trip and fall into traffic if you run for the bus than if you don't?

Fruit flies have specific patterns of sensory bristles on their legs and honeybees have distinctive coloring on their abdomens, but most of the structural gains caused by changes in HOX genes have been detrimental

"Laboratory-bred four-winged fruit flies are a famous example of how relatively simple genetic alterations in regulatory regions of the HOX genes candramatic change the body shape of an animal." "But because these flies can't survive in the wild, anti-evolution proponents have seized on them--not as good examples of how genes drive evolution, but as proof that genes can only make animals less functional."

The two- to four-inch stickleback fish are great research subjects because they evolve rapidly and dramatically in response to changing environmental conditions. A lake full of fish-eating insects houses sticklebacks with smaller and shorter spines to grab. A pond with larger fish or birds that swallow their fish sticks whole is likely to have a lot of sticklebacks. In the open ocean, armored plates and fearsome spines are the way to go if you want to hide a slippery fish.

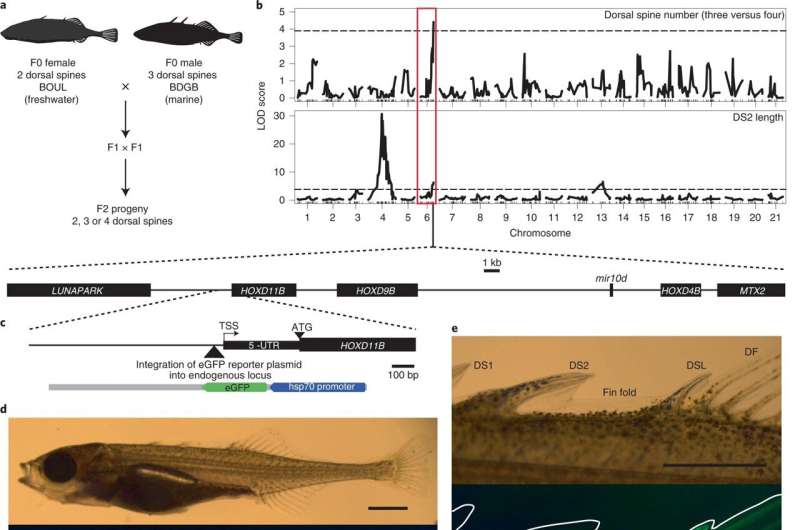

The study began with a spot of water. The graduate students crossed the two-spined female and three-spined male stickleback from the freshwater lake in British Columbia to the salty waters of Bodega Bay. They looked at the number and shape of their spines after crossing the offspring from that match. Most of the grand-fish had at least one spine, but six had two and 21 had four. HOXDB is a member of the HOX family of genes and has been identified as the cause of differences in the fish's spin.

There is a connection between genes and the body.

Wucherpfennig continued to collect and cross sticklebacks from multiple North American lakes and streams, studying their genetic makeup and using CRISPR methods to confirm the effects of the HOXDB genes on their spine. She found a panel of changes in regions near the HOXDB genes that were associated with changes in the armor of wild fish.

Some of the stickleback populations in Nova Scotia have more than one spine. Nature left the coding region intact but altered how and when it is expressed during normal development to add structures. New structures are helping fish thrive in a completely wild environment.

The recent evolution of new spine patterns in two different stickleback species was caused by repeated changes in the regulatory regions of the HOXDB genes. They want to know if changes in fish are related to changes in humans.

Evolutionary change is governed by predictable rules. "You're right," she said. Natural species use the same trick over and over, or do they have to invent a new trick each time? It's the same thing in these sticklebacks from different places. We show that nature adds major structures to create animals that are more suited to the environment, and that it does so repeatedly using the same master regulatory genes. The argument for progressive evolution has been debated for decades.

More information: Julia I. Wucherpfennig et al, Evolution of stickleback spines through independent cis-regulatory changes at HOXDB, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-022-01855-3 Journal information: Nature Ecology & Evolution