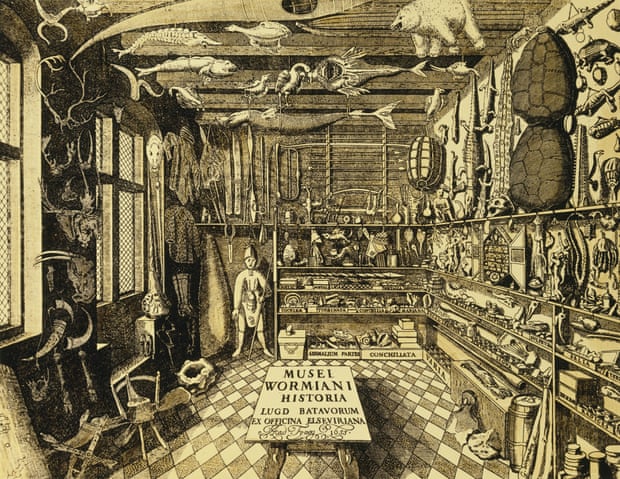

There was a room in a house in the early 17th century that was filled with hundreds of objects, including bones and shells, taxidermised birds, and a stuffed polar bear. The Museum Wormianum was put together by the doctor and philosopher Ole Worm. Four hundred years after it was founded, this quintessential cabinet of curiosities still inspired two professors. What made the worm to collect? Which signals were coming from his brain? The eccentric would have behaved differently if he had access to the internet.

The neurological, historical, philosophical, and linguistic foundations of curiosity are investigated in Zurn and Bassett's latest work. What is it about curiosity that makes it interesting? How does it work? The academics argue in a manuscript that curiosity is a network. They wrote in the book that it works by linking ideas, facts, perceptions, sensations and data points together.

They think it all started with their grandmother. She had a basement and crawl space full of antiques, including chairs, books, crystal glasses, silverware, paintings and buttons. Zurn says he vividly remembers crawling on his hands and knees and getting lost in mazes of old things when he was younger. The twins said this cabinet influenced their minds. Zurn says that when you are four years old, time and history become real.

The twins’ parents believed that men should go to college and have careers while women should instead get married

You wouldn't know that from reading their book. The former is a professor of political philosophy at American University in Washington DC while the latter is a professor of physics, astronomy, engineering, neurology and Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania. The Roman essayist Plutarch's antidotes to the "disease" of curiosity, such as not having sex with your wife, are included in Curious Minds.

Where else could you read about the motivation circuit of the brain before reading about the work of a Japanese poet? The twins' interest in Ole Worm was similar to the book's multi-disciplinary approach.

Zurn says that the twins were home-schooled in a way that gave them a lot of flexibility in what they learned. There was a tight constraint on who we could be socially with.

Men should go to college and have careers while women should get married and serve their husbands according to the twins' parents. At birth, the twins were assigned male and female pronouns.

The school was my life's work. Zurn says that he knew from a long time ago that this was a part of his life. We came up against the expectation that we wouldn't continue on into academics.

The seeds that had been sown couldn't be replanted because they made the twins curious about everything. It wasn't clear at the beginning of our careers that we would ever have a chance to write a book together because our areas were so wildly different That is when we began talking. Seven years of research was done after that talking. It is a culmination of that.

Neuroscience and philosophy complement one another. The book begins with a question: what is curiosity? The field of science isn't ready to define curiosity and how it's different from other cognitive processes There are rich historical definitions and styles that we can put back into neuroscience to see if we can see them in the brain.

In the introduction to the book, the twins state that curiosity is a growth principle of the network and that knowledge is a network as well. Zurn says being curious is connecting ideas and people. Is he and his twin really interested in this theory because they are twins?

Zurn said yes. We have two independent bodies and two independent minds, yet we have created our knowledge of our worlds together. The more we have developed that connectional theory of curiosity, the more it makes sense.

Twins in different fields are writing a book together. When one of them was on leave, Zurn and Bassett would write it at different times. Zurn says that there are a lot of emails from Dani saying "Look at this quote from this book" and "Look at this article" The editors of the twins' book were surprised when they said they wanted to include hand-drawn diagrams to show the theories in the book.

When the editors saw examples, they became excited about the idea. The backs of two smiling faces are missing and replaced with a series of connected lines and dots to show how different people connect different pieces of knowledge. Do you find yourself jumping from a list of entertainment affected by the September 11 attacks to a page aboutCream cracker when you click on it?

You could be a busybody, a hunter, or a dancer. Three basic modes of practicing curiosity conform to three Archetypes according to one interesting theory. The busybody makes it their business to know everything and anything, they want to know as much as they can. The hunter has a focused curiosity and they are relentless in their pursuit of new discoveries. The dancer uses their imagination to leap.

Zurn looked at the history of western intellectual thought to develop these Archetypes. He discovered that busybodies, hunters and dancers were words and concepts that kept coming up. Zurn is pretty sure these aren't the only Arche of curiosity, but they're a good place to begin.

At times, they feel more like one type of person than another. They are very curious about a lot of different fields and read a lot. They are more like a hunter when they are researching. Zurn agrees that we can embody these different Archetypes at different times in our lives.

Here is a question you might suddenly be curious about: what is the purpose? How can we apply the knowledge of the Arche of Brilliance? Education should be de-disciplined, meaning that learners should be encouraged to drift between fields. Abraham Flexner was an education reformer who advocated the usefulness of useless knowledge. Flexner questioned the narrow approaches that forced academics to answer questions.

It's important to be open about how the mind moves. The twins examine marginalisation, power and privilege in the book. Not everyone is celebrated for having the same qualities as Leonardo da Vinci, who was known for being obsessive about note-taking and sketching.

The capacity to think across and beyond established frames of knowledge can be greatly diminished depending on who you are and where your curiosity takes you.

The cornerstones of their subfields, fields, or founders of new fields, were told no. They didn't listen.

The constraints of expectation didn't deter Zurn and Bassett from embarking on a half-decade expedition through the science and philosophy of curiosity. Zurn says that the book is an invitation to the reader to join the journey with them.

The Power of Connection is a book by the authors. You can order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges can be applied.