In a waiting room at the Mortimer Market Centre, a sexual health clinic in central London, a steady stream of men who have sex with men are waiting to receive their first monkeypox vaccine. Since vaccines started to be delivered here in early July, all available slots have been filled, and it is a hot day.

Most people don't know much about the vaccine or the monkeypoxviruses. Gay and bisexual men make up 98% of the cases of this outbreak, according to the World Health Organization. There is some protection for the 2,500 men who have passed through these doors. The disease can be fatal.

A nurse gives a vaccine to 20-year-old Callum Bowyer, who has been trying to get it for a long time. Some of my friends have monkeypox and they have to be isolated for up to four weeks. I don't like that. It has been difficult to find a way to protect myself. He couldn't find a clinic in either area that would give him a jab or a suggestion of where he could get one.

He said he had a monkeypox scare. After London's Pride celebrations. When I had spots on my body, I was told to travel to Soho to get a test, so I had to sit on a busy train. Bowyer was able to get the all clear. Finding a vaccine became impossible after this close call. After a friend tipped him off, he was able to get the appointment. I speak to others who describe similar struggles, such as phones going unanswered.

Despite being in a high-risk group, Ron Lithgo was not able to find a clinic in east London. He got a place here after getting a referral from a club. Nobody has a clue where to get one, but you can find out if you are eligible very easily.

The waiting room has been emptied. With appointments over for another day, Kim Lombardi, the clinical lead for the vaccine team, sets out just how high the demand has been. She says they see up to 200 people a day. We could see more if we had more supplies.

Staff say recent weeks in the clinic feel like the 90s. It feels like a club when we deliver the vaccine in the evening. A lot of the older staff say it feels like the old days when we put the music up. There are echoes of the AIDS epidemic. The younger ones have been anxious. Something going around that nobody knows much about is alarming for them. It's frightening for them.

The demand for appointments in sexual health services has never been as high as it is now. The regular patients who were eligible for the vaccine after the vaccine centre was set up were HIV-positive patients, men with multiple partners who participate in group sex or attend sex on premises. The response has been huge. They will go as soon as we put appointments online. 100 slots will have been filled within minutes. There are people waiting.

The clinic is unable to offer any new vaccines due to the short supply. National rationing means that jabs will no longer be given to people after they've been exposed to monkeypox. She says that patients understand when they are told there are no appointments. You can understand why others are upset. Many people are saying they are in the high risk group. It feels like an underestimation.

The first known case of monkeypox in humans was 50 years ago. John McSorley is a sexual health and HIV clinician and a past president of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. Its circulation in Europe and other parts of the world is atypical.

The close networks and contacts of MSM appear to have been exploited by the viruses. This is a virus that can be transmitted through close skin-to-skin contact. It's not mandatory to have sexual contact with someone.

McSorley says that most of the symptoms of monkeypox are at the "milder" end of the spectrum. Poxes or spots may last seven to 10 days, healing with mostly complete improvement. At the opposite end of the spectrum, in Europe a small percentage of people have had more serious problems, such as in and around the mouth, neck and genital area, causing difficulty or pain when eating or excreting.

Most infections will be over in 21 days. There are long-term problems for some people. There can be deaths from this virus in Africa where it affects children and babies, pregnant women or people with significant underlying health conditions. According to the African Centre for Disease Control, there have been 75 deaths in Africa in the next two years.

Men who have sex with men between the ages of 16 and 65 are more likely to be affected by this outbreak. For example, two men in their 30s in Spain with no underlying health conditions died recently.

There is a strong case for mass vaccinations of those most at risk. All evidence shows that monkeypox won't be the same as Covid. McSorely says that it shouldn't happen given the family of Viruses it comes from. The vaccinations are showing results. The number of cases in the UK has slowed, with an average of 20 cases being confirmed a day, compared with 52 in June.

The outbreak could be stopped by replacing immunity with vaccine. We're about to run out of drugs.

The global situation doesn’t explain or excuse the initial inadequate and shambolic response and rollout from government

The government could be doing more. McSorley says that they have the power to increase or decrease spending. All responses have had to be delivered from existing resources. The Department for Health and Social Care pointed out to the Guardian that local authorities can use the public health grant to invest in sexual health services.

More than 30,000 MSM have received their first monkeypox vaccine according to the UK Health Security Agency. They should get a second chance if everything goes according to plan. The modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine is used to protect against a variety of diseases. There is much more to be done. A further 100,000 are expected to arrive in late September after the UK government ordered 50,000. The 75,000 people would be treated. According to a coalition of sexual health experts, including representatives from the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV, the National Aids Trust and the Association of Directors of Public Health, there should be at least 130,000 men needing the vaccine.

There is only one supplier of the vaccine worldwide and part of its production line is closed for repairs. The company doesn't know if it can meet demand on its own as case numbers increase, but it is looking into the possibility of using expired doses to bridge the gap.

There have been failures closer to home. The global situation doesn't explain or excuse the initial inadequate and shambolic response from central government and national agencies.

The official says that the UKHSA and the English health service were not very concerned by the outbreak at first. They didn't work together because they fought with one another. People in various agencies have told me that if it becomes endemic in gay men, then so be it.

The official says that there could have been more vaccines here if the government had moved quicker.

Dr Andrew Lee is the UKHSA's monkeypox incident director. "We acted immediately to tackle the spread of the monkeypox virus, and have worked continuously with a range of stakeholders to investigate the outbreak, alert people to the symptoms and support those affected."

On August 22, the UKHSA announced a trial of fractional dose across a limited number of vaccine sites. The same results can be achieved if one-fifth of the current vaccine is delivered into a patient. Access to the vaccine will grow quickly if this is implemented. The president of the Association of Directors of Public Health believes there has been improvements.

There is now a clear consensus that we are aiming to end the outbreak in the UK and prevent it from becoming endemic. There is more to be done. We are not close to national government funding for the extreme and unique pressure sexual health services are under, and we don't have a support package for men who have to isolation with monkeypox.

There is a risk that monkeypox will become endemic if vaccine supplies dry up. It will be hard to eliminate the health inequalities for gay and bisexual men because it will cost hundreds of times as much as a vaccine to eliminate it.

Many gay and bisexual men really don’t trust the state to look out for their sexual health. And I don’t blame them

Men of the same sex are advocates for their own health. This is a necessity after decades of being let down by central government. Many still think the government doesn't care about MSM's sexual health, despite the fact that much has changed since the 1980's and 90's nakedly homophobic response to HIV and Aids.

Greg Owen, a sexual health and HIV activist who now works with the Terrence Higgins Trust was a key figure in the fight for the drug to be made available on the National Health Service. The FDA approved the drug for this purpose in July of last year. More than 30,000 men were diagnosed with HIV in the UK during the time it took for the treatment to be made widely available.

Owen says that many gay and bisexual men don't trust the state to look out for them. I don't think I'm responsible for them.

Owen is swamped with requests for help from people who are experiencing symptoms and others who want to know where to get a vaccine. This period has been traumatic for many.

He says there's a problem from HIV and Aids. People older than me are freaked out by the sight of young gay and bisexual men with their faces covered in STDs. Those who lived through that epidemic will feel a big sense of relief. Owen argues that there are few comparisons to be made between HIV/Aids and monkeypox.

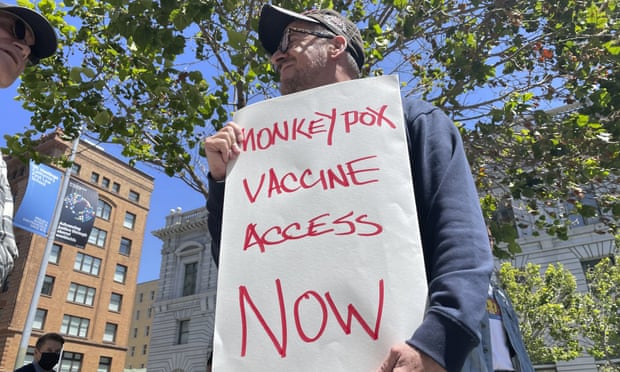

Owen says that this is a community who are attacked for who they have sex with. There has been no extra money made available to deliver the vaccine or run a proper national information campaign. Some people won't even know about the risk, and those who can't get the vaccine are having to place themselves at risk or not have sex at all. It's out of line.

Ryan Coleflex is in a similar situation. He is eligible for a vaccine and has no idea when he will get one. Coleflex says, "I'm seeing peers post on social media of how they're affected, often with graphic photos to highlight their struggle." I can't do anything else.

The proximity of the monkeypox outbreak to Covid has been claimed as a benefit by clinicians. Two and a half years into the Pandemic, the public's willingness to present themselves for a vaccine is still normal. It is difficult for Owen to compare the two vaccine programmes.

He said that they saw what happened with Covid. The vaccine was made available to people who needed it. The people were told they would be called in as soon as possible if they changed their behavior. We are not waiting for breakthrough in science with this. Owen says that there is a vaccine. Everyone who wants a vaccine will not be given access to it when it becomes available. This community is once again being put at risk. It doesn't feel like there's much going on. I don't think it's overt homophobia It isn't the same as what happened with HIV and AIDS. It feels too similar.