There was an Easter Monday in 1957. Crowds gathered for the half marathon in Doncaster, but there was a heavy gloom in the air.

The starting area was crowded with race stewards who had been told to stop at all costs.

He was a gatecrasher who should not be allowed to race. He was a champion fighting injustice.

As the start time drew closer, runners pressed forward. The race was about to start when the local mayor raised his arm to the sky. Another sound was heard in the air.

A spectator dressed in a long coat and a large hat threw his disguise out the window as he jumped into the race. The spectators roared their approval, and the stewards couldn't keep up with the runners as they disappeared down the road.

John Tarrant had both triumph and tragedy. He ran multiple world records but was denied his full share of glory by the authorities who banned him from racing.

They couldn't stop him. He was a great competitor. A person without a number. The person called him the Ghost Runner.

Tarrant grew up in poverty but his parents were still loving him. For a time, life progressed as a child should.

In 1940, with their mother's health failing and their father calling up to man London's anti-aircraft batteries, the brothers were sent to a children's home. They will stay there for seven years.

At the best of times, life at Lamorbey was dull, but at the worst of times, it was terrifying. The Tarrant boys were getting worse. Their mother died from Tuberculosis.

Their father got them in August 1947. He moved his family to the edge of the Peak District after remarrying and having a new born baby.

The young Tarrant ran with a stubbornness that quickly consumed him in this beautiful and savagely hilly landscape. It was his way of getting over something. He became known for his ability to push himself further than most would consider trying.

The chair of the Ghost Runners running club in Hereford says that Tarrant used running as his psychological help.

You're going to be angry and rebel after that.

Tarrant took up boxing when he was 17 years old. He earned himself a total of £17 over the course of two years. He quit the sport in 1951 because he didn't have much of a chance as a boxer.

A lot of manual labour jobs came and went in order to get more time to run. Tarrant took his training gear with him on his honeymoon. He wanted to go to the Olympics but first he had to join a club.

According to a moral standard supposedly inspired by the Ancient Greeks but which stank of inequality and exclusion, British athletics in the 1950's was governed according to a moral standard.

The amateur sports were not to be sullied by those who had ever received payment for competing. As Britain recovered from World War Two, it was a rule that disproportionately affected the poor.

Tarrant felt it was necessary to declare his boxing exploits when applying to join the Amateur Athletic Association.

His subscription fee was returned two weeks later. He was told that he would not be allowed to compete in amateur athletics for the rest of his life. He tried to get in touch with officials, but they wouldn't listen.

Tarrant and his brother were driven by a burning sense of injustice. Is it not possible to simply run in theAAA races? It could even spark a debate within the media.

Things got off to a bad start. They arrived late to race starts in Yorkshire. There was nothing left to chance when Tarrant arrived for the marathon.

He made his way through the crowd to the start line.

He was in the middle of the race when he burst clear after 11 miles. Tarrant's approach to competition would be almost reckless and he would come with one gear.

He held up until mile 19 when he was caught by the pack. He fell to the ground two miles from the finish because his body was exhausted.

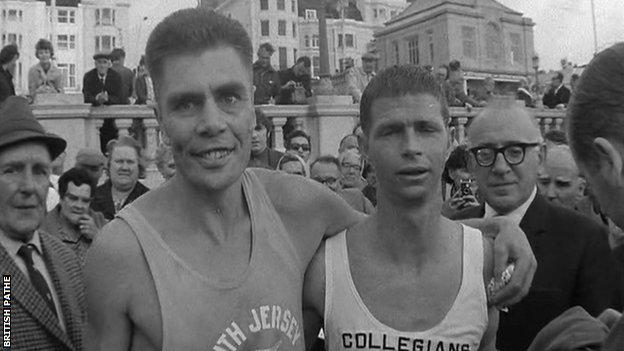

Tarrant's efforts in the city had caught the attention of onlookers. The Daily Express dubbed him the Ghost Runner after he gave a press conference before boarding the train.

He gatecrashed races all over the country over the next few years. He had to slalom through a pack of stewards trying to catch him at the start of races as media attention grew. When he won, his success would be met with silence or a public admonishment over the loudspeaker.

Despite the official line, Tarrant was a hugely popular character who was cheered on by hundreds, sometimes thousands of spectators.

Bill Jones is the author of The Ghost Runner - The Tragedy of the Man They Couldn't catch.

He was a working class hero in the 1950s.

Tarrant's ban had been overturned in a letter from theAAA. One month after Harold Abraham wrote an article about the case against Tarrant, the decision was made.

elation gave way to revulsion Tarrant had been cleared to run in British races, but he wouldn't be allowed to represent his country internationally.

Tarrant established himself as one of the best long-distance runners in Britain after his dream of running at the Olympics was crushed.

In the 1960s, he won a number of races, including the London toBrighton 54-mile race twice, and the 48 mile race three times. His Territorial Army-110-mile march record was set in 1959 and he set two new world records.

He failed to finish many races because of his stomach complaints, just like he failed to finish inLiverpool. He could rule or be seen staggering away on any day.

A sense of unhappiness was setting in by the 1960's. Tarrant wanted to compete around the world.

The Comrades Marathon in South Africa is said to be the oldest ultra- marathon in the world.

It was still a white male race. Women and black competitors weren't allowed to compete. Nevertheless, a few still competed.

Tarrant was one of the interlopers after South African officials rejected his application. The Ghost Runner had never been on the fringes before.

Tarrant thought a fourth place finish was below par. He came back the next year and entertained the idea of moving.

His second Comrades looked like a complete disaster but was salvaged by a brave display that saw him finish 28th after suffering stomach issues along the way.

Tarrant failed to finish on both occasions. The unfulfilled dream of conquering the contest led to his defining moment.

A new multi-ethnic race was rumored to be open to all during the 1969 Comrades. It was not clear if it would go ahead and how many white runners would compete.

John Tarrant was the lone white competitor at the Gold Top Marathon on the morning of 6 September 1970. He won it in less than six hours.

The number of white runners doubled after Dave Upfold began training with Tarrant.

Upfold said they were expecting the police and the army.

We weren't allowed to compete in 1971 because there wasn't anything.

It was the beginning of the acceptance that people of color could run.

The Comrades were fully integrated with women and all ethnicities by 1975, and Tarrant was a part of that.

Tarrant improved his time by three minutes when he won the 1971 gold top.

He woke up with vomit and blood after a haemorrhage. He ran over 100 miles a week after being discharged from the hospital. One final epic remained despite all being not well.

A group of runners, including a 39-year-old Tarrant, started the Radox 100 Mile track race.

He was struggling badly, alternating between walking and jogging, with the race leader 17 minutes ahead. The once imperious ghost was fading fast and few had any hope of him winning.

Tarrant dug into what propelled him and kept going. The gap began to shrink as he got closer. The unthinkable seemed like it could happen.

In the end, thanks to a late burst, Bentley finished 14 minutes ahead of Tarrant, who ended his last major race in an appalling condition - his lips blue, frothing from his mouth. The Ghost Runner was shepherded into a waiting car by his brother, who was always there for him. It's forever.

According to Jones' book, The Ghost Runner, Tarrant's greatest race was the one he organised.

He was in a state of mortally ill at the time. The Almighty knows how he did it. You were able to be there.

Tarrant was eventually diagnosed with stomach cancer. He died at 42 years old.

A sculpture in his honor was created by teenagers living in a nearby residential home.

He believed in fair play. Upfold says fairness for himself, fairness for everyone, and equality for all. The name John Tarrant is still remembered nearly 50 years later.

He was determined to show people what he could do even though he wasn't allowed to win.

It wasn't just about running, that's for sure. It was about believing in yourself. People love this story because of that.