If there is one thing that the COVID-19 epidemic has brought into relief, it is how easy it is for people to believe in conspiracy theories. In less than two and a half years since COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, we have written about many people who we had never heard of before. The authors of the Great Barrington Declaration, Martin Kulldorff, Jay Bhattacharya, and Sunetra Gupta, all had been well-respected before they turned to COVID-19 contrarian. We were familiar with many of the scientists who made their turn to contrarian but whose turn to contrarianism and science denial shocked me, such as John Ioannidis. I wasn't surprised when scientists and physicians who had been antivaccine pivoted to COVID-19 minimization and anti-vaccine. Looking over the list of these people and others, one can find a number of similarities but not all of them. Most of them have an interest in libertarian politics. Few of them have any expertise in infectious diseases. Sunetra Gupta is a British infectious disease epidemiologist and a professor at the University of Oxford. She is a modeller, but early in the Pandemic she disagreed with the scientific consensus that by March 2020 more than half of the UK population might have been exposed to the novel coronaviruses. Gupta seems to have doubled down instead of wondering where she went wrong. Most of the others have little or no relevant experience in infectious disease. Kulldorff and Bhattacharya have shown up frequently on Fox News to attack public health interventions and mandates targeting the swine flu epidemic. What is the main thing? The study was published in ScienceAdvances last month. Steve Novella wrote about it on his personal blog the week that it was published, but I wanted to add my take and integrate it into a more general discussion of how people can fall prey to criminals based on their education and profession. Steve said in his post that a good first approximation of what is most likely to be true is to understand and follow the consensus of expert scientific opinion. He said that it was just chance. It doesn't mean that the experts are always right, or that there is no role for minority opinions. Steve said it was rather.

It mostly means that non-experts need to have an appropriate level of humility, and at least a basic understanding of the depth of knowledge that exists. I always invite people to consider the topic they know the best, and consider the level of knowledge of the average non-expert. Well, you are that non-expert on every other topic.

The title of the study suggests that knowledge overconfidence is associated with anti-consensus views on controversial scientific issues. Humility has been emphasized by the crew. This need is not limited to science in which a person is an expert. I am an expert in breast cancer because I know a lot about the biology of the disease. I am not a medical oncologist, I am a surgical oncologist, and I hope that my medical colleagues don't tell me who is a surgical candidate. I can be considered an expert in some areas of basic and translational science, such as breast cancer biology, if I have done research and published in that area. After studying anti-science misinformation, the antivaccine movement, and conspiracy theories for almost two decades, I think I have a certain level of expertise in these areas. I tended to stick with the scientific consensus if new evidence suggested that I should change my mind. I immediately recognized the same sorts of science denial, antivaccine tropes, and conspiracy theories that I had written about in the past, which are what I wrote about in my previous writings. The last of us had been predicting before the FDA issued emergency use authorizations for the COVID-19 vaccine and I wrote about it within weeks of the vaccine's release. If you don't know the kinds of conspiracy theories that have been spreading among antivaxxers, you wouldn't know that everything old is new again, there is nothing new under the sun, and antivaxxers tend just to recycle. I think that some of the people above might not have turned antivax if they'd known these things before. There are investigators from Portland State University, the University of Colorado, Brown University, and the University of Kansas. The title of the study suggests that it's about the cognitive bias known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, in which people wrongly overestimate their ability in certain areas. There are criticisms of the model, but it has held up well as a possible explanation of how people think. The authors point out one important point before describing their methods.

Opposition to the scientific consensus has often been attributed to nonexperts’ lack of knowledge, an idea referred to as the “deficit model” (7, 8). According to this view, people lack specific scientific knowledge, allowing attitudes from lay theories, rumors, or uninformed peers to predominate. If only people knew the facts, the deficit model posits, then they would be able to arrive at beliefs more consistent with the science. Proponents of the deficit model attempt to change attitudes through educational interventions and cite survey evidence that typically finds a moderate relation between science literacy and pro-consensus views (9–11). However, education-based interventions to bring the public in line with the scientific consensus have shown little efficacy, casting doubt on the value of the deficit model (12–14). This has led to a broadening of psychological theories that emphasize factors beyond individual knowledge. One such theory, “cultural cognition,” posits that people’s beliefs are shaped more by their cultural values or affiliations, which lead them to selectively take in and interpret information in a way that conforms to their worldviews (15–17). Evidence in support of the cultural cognition model is compelling, but other findings suggest that knowledge is still relevant. Higher levels of education, science literacy, and numeracy have been found to be associated with more polarization between groups on controversial and scientific topics (18–21). Some have suggested that better reasoning ability makes it easier for individuals to deduce their way to the conclusions they already value [(19) but see (22)]. Others have found that scientific knowledge and ideology contribute separately to attitudes (23, 24). Recently, evidence has emerged, suggesting a potentially important revision to models of the relationship between knowledge and anti-science attitudes: Those with the most extreme anti-consensus views may be the least likely to apprehend the gaps in their knowledge.

Steve described it as a "superDunning-Kruger" The authors talk about what their research contributes to general knowledge.

These findings suggest that knowledge may be related to pro-science attitudes but that subjective knowledge—individuals’ assessments of their own knowledge—may track anti-science attitudes. This is a concern if high subjective knowledge is an impediment to individuals’ openness to new information (30). Mismatches between what individuals actually know (“objective knowledge”) and subjective knowledge are not uncommon (31). People tend to be bad at evaluating how much they know, thinking they understand even simple objects much better than they actually do (32). This is why self-reported understanding decreases after people try to generate mechanistic explanations, and why novices are poorer judges of their talents than experts (33, 34). Here, we explore such knowledge miscalibration as it relates to degree of disagreement with scientific consensus, finding that increasing opposition to the consensus is associated with higher levels of knowledge confidence for several scientific issues but lower levels of actual knowledge. These relationships are correlational, and they should not be interpreted as support for any one theory or model of anti-scientific attitudes. Attitudes like these are most likely driven by a complex interaction of factors, including objective and self-perceived knowledge, as well as community influences. We speculate on some of these mechanisms in the general discussion.

The authors estimate the opposition to scientific consensus through five studies.

In studies 1 to 3, we examine seven controversial issues on which there is a substantial scientific consensus: climate change, GM foods, vaccination, nuclear power, homeopathic medicine, evolution, and the Big Bang theory. In studies 4 and 5, we examine attitudes concerning COVID-19. Second, we provide evidence that subjective knowledge of science is meaningfully associated with behavior. When the uninformed claim they understand an issue, it is not just cheap talk, and they are not imagining a set of “alternative facts.” We show that they are willing to bet on their ability to perform well on a test of their knowledge (study 3).

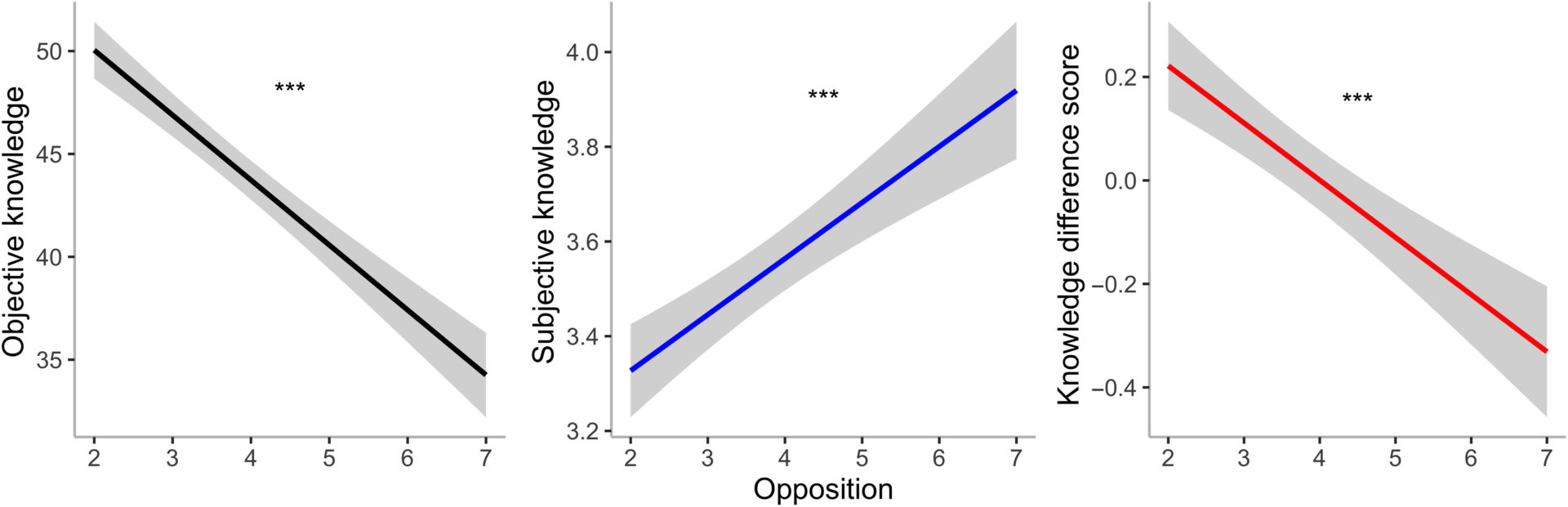

This graph depicts the key part of the study. There is a picture in the first figure. Predicting of relationships between opposition and objective knowledge, subjective knowledge, and the knowledge difference score is the model's overall prediction. Higher levels of opposition to a scientific consensus are associated with lower levels of actual scientific knowledge, higher self-assessments of knowledge, and more knowledge overconfidence (operationalized here as the increasing negative magnitude of each respondent’s knowledge difference score). ***P < .001.[/caption] Because there could be differences based on topic, the authors then broke their results down individual contentious area: [caption id="attachment_81132" align="aligncenter" width="1920"] Opposition is associated with subjective knowledge and with objective knowledge, but not for all issues.Overconfidence versus scientific consensus

Fig. 2. The relationship between opposition and subjective and objective knowledge for each of the seven scientific issues, with 95% confidence bands.

Fig. 2. The relationship between opposition and subjective and objective knowledge for each of the seven scientific issues, with 95% confidence bands.

The relationship between opposition to the scientific consensus and objective knowledge was negative for all episodes other than climate change, while the relationship between opposition and subjective knowledge was positive for all issues other than climate change.

According to the authors, the relation between opposition and objective knowledge is less negative than the relation between opposition and subjective knowledge, which is less positive, when it comes to politics. One way that this result might be interpreted is that advocates who are against the subject go out of their way to learn as much as they can about it. Knowledge doesn't lead to understanding, but rather to more skilled at motivated reasoning, like picking and choosing data that supports one's beliefs

Study subjects with different levels of opposition to a scientific consensus might interpret their subjective knowledge differently. To test this, the authors created a measure of knowledge confidence that would encourage participants to report their genuine beliefs. The chance to earn a bonus payment was given to subjects if they could score above average on the objective knowledge questions or if they could take a smaller guaranteedPayout.

The results were expected.

As opposition to the consensus increased, participants were more likely to bet but less likely to score above average on the objective knowledge questions, confirming our predictions. As a consequence, more extreme opponents earned less. Regression analysis revealed that there was a $0.03 reduction in overall pay with each one-unit increase in opposition [t(1169) = −8.47, P< 0.001]. We also replicated the effect that more opposition to the consensus is associated with higher subjective knowledge [βopposition = 1.81, t(1171) = 7.18, P < 0.001] and lower objective knowledge [both overall science literacy and the subscales; overall science literacy model βopposition = −1.36, t(1111.6) = −16.28, P < 0.001; subscales model βopposition = −0.19, t(1171) = −10.38, P < 0.001]. Last, participants who chose to bet were significantly more opposed than nonbetters [βbet = 0.24, t(1168.7) = 2.09, P = 0.04], and betting was significantly correlated with subjective knowledge [correlation coefficient (r) = 0.28, P < 0.001], as we would expect if they are related measures. All effects were also significant when excluding people fully in line with the consensus (see the Supplementary Materials for analysis).

The authors asked the same questions about whether or not study subjects would take the COVID-19 vaccine. The results of previous studies were duplicated. The results of the study on how much study participants think scientists know about COVID-19 were surprising.

To validate the main finding, we split the sample into those who rated their own knowledge higher than scientists’ knowledge (28% of the sample) and those who did not. This dichotomous variable was also highly predictive of responses: Those who rated their own knowledge higher than scientists’ were more opposed to virus mitigation policies [M = 3.66 versus M = 2.66, t(692) = −12, P < 0.001, d = 1.01] and more noncompliant with recommended COVID-mitigating behaviors [M = 3.05 versus M = 2.39, t(692) = −9.08, P < 0.001, d = 0.72] while scoring lower on the objective knowledge measure [M = 0.57 versus M = 0.67, t(692) = 7.74, P < 0.001, d = 0.65]. For robustness, we replicated these patterns in identical models controlling for political identity and in models using a subset scale of the objective knowledge questions that conservatives were not more likely to answer incorrectly. All effects remained significant. Together, these results speak against the possibility that the relation between policy attitudes and objective knowledge on COVID is completely explained by political ideology (see the Supplementary Materials for all political analyses).

It's possible that this could explain why some people who identify as liberal or progressive have fallen for contrarianism.

Results from five studies show that the people who disagree most with the scientific consensus know less about the relevant issues, but they think they know more. These results suggest that this phenomenon is fairly general, although the relationships were weaker for some more polarized issues, particularly climate change. It is important to note that we document larger mismatches between subjective and objective knowledge among participants who are more opposed to the scientific consensus. Thus, although broadly consistent with the Dunning-Kruger effect and other research on knowledge miscalibration, our findings represent a pattern of relationships that goes beyond overconfidence among the least knowledgeable. However, the data are correlational, and the normal caveats apply.

I wonder if the results have relevance in suggesting how scientists and physicians who should know better could hold anti-consensus views. Let's look at the case of John Ioannidis. He was known as a critic of science. His publication record covers documentation of deficiencies in the scientific evidence for a wide range of scientific subjects, from the effect of nutrition on cancer to all clinical science. I was starting to become uncomfortable with his attitude as being more knowledgeable about everything after he began abusing science to attack scientists who held consensus views about COVID-19. I would think that the overconfidence in his own knowledge that was described in this study had already caused him to get sick.

He had criticized the evidence base for cancer interventions. He is a doctor. He documented medical reversals, when an existing medical practice is shown to be no better than a lesser therapy. Steve and I talked about this concept at the time and both agreed that it was missing a lot of nuances. By the time of the swine flu, Prasad had criticized those of us who were fighting pseudoscience in medicine as, in essence, wasting our medical skills, and denigrating such activities as being below him, as a pro basketball star, as he dunked on a 7. I would think that the overconfidence in his own knowledge that was described in this study had already started to affect him. It's possible that all of the contrarian doctors who went anti-consensus shared this overconfidence before the epidemic.

The study doesn't address the role of social affirmation in reinforcing anti-consensus views and even radicalizing such "contrarian doctors" further into anti-science views Many of the physicians and scientists on the list have large social media presences. Although he frequently brags about not being on social media, he does receive a lot of invitations to be interviewed in more conventional media from all over the world because of his pre-pandemic fame as the most published living scientists. Financial rewards are available to many of these doctors. Many of them have Substacks in which they monetize their views.

These are good topics for other studies Let's move on to the general public that consumes misinformation.

Skeptics have known about this for a long time. Lack of information isn't the reason for science denial. Trying to drive out bad information with good information doesn't work very well because it's more than that.

The findings from these five studies have several important implications for science communicators and policymakers. Given that the most extreme opponents of the scientific consensus tend to be those who are most overconfident in their knowledge, fact-based educational interventions are less likely to be effective for this audience. For instance, The Ad Council conducted one of the largest public education campaigns in history in an effort to convince people to get the COVID-19 vaccine (43). If individuals who hold strong antivaccine beliefs already think that they know all there is to know about vaccination and COVID-19, then the campaign is unlikely to persuade them.

Instead of interventions focused on objective knowledge alone, these findings suggest that focusing on changing individuals’ perceptions of their own knowledge may be a helpful first step. The challenge then becomes finding appropriate ways to convince anti-consensus individuals that they are not as knowledgeable as they think they are.

It is not easy to do this. Hard core antivaxxers are not persuadable. Their anti-vaccine views are similar to religion or political affiliation in that they are hard to change. It is possible to change these views, but the effort and failure rate are too high to make these people targets of science communication. It is the fence sitters who are the most likely to change their minds, if you will, as a consequence of this principle.

Last week, a study from authors at the Santa Fe Institute was published in the same journal suggesting that I should be rather humble, as I might not be entirely on the right track, in that people do tend to shape their beliefs according to their social networks. The authors mention it often.

Skepticism toward childhood vaccines and genetically modified food has grown despite scientific evidence of their safety. Beliefs about scientific issues are difficult to change because they are entrenched within many interrelated moral concerns and beliefs about what others think.

Social moral beliefs and concerns and personal ideology are some of the reasons why people gravitate to anti-consensus views. Information alone, although a necessary precondition to change minds, is usually not enough to change minds. It is equally important to identify who is changeable with effort.

The authors used this rationale to look at two scientific issues, vaccines and genetically modified organisms.

In this paper, we consider attitudes toward GM food and childhood vaccines as networks of connected beliefs (7–9). Inspired by statistical physics, we are able to precisely estimate the strength and direction of the belief network’s ties (i.e., connections), as well as the network’s overall interdependence and dissonance. We then use this cognitive network model to predict belief change. Using data from a longitudinal nationally representative study with an educational intervention, we test whether our measure of belief network dissonance can explain under which circumstances individuals are more likely to change their beliefs over time. We also explore how our cognitive model can shed light on the dynamic nature of dissonance reduction that leads to belief change. By combining a unifying predictive model with a longitudinal dataset, we expand upon the strengths of earlier investigations into science communication and belief change dynamics, as we describe in the next paragraphs.

A group of almost 1,000 people who were at least somewhat skeptical about the efficacy of genetically modified foods and childhood vaccines would change their beliefs as a result of an educational intervention. A longitudinal study of beliefs about GM food and vaccines was carried out at four different times over three waves of data collection. The National Academies of Sciences reported on the safety of GM food and vaccine during the second wave. Participants were divided into five experimental groups for the GM food study and four experimental groups for the study of childhood vaccines with one control condition in each study in which they did not receive any intervention. The same message was given to all experimental conditions. The cognitive network model was used to find out how beliefs would change in the wake of the educational intervention.

It was found that people who had a lot of conflicting beliefs were more likely to change their beliefs after seeing the message. The authors found that people are driven to believe differently. The authors commented in an interview that people with little dissonance showed little change in their beliefs after the intervention and that people with more dissonance were more likely to show more change.

“For example, if you believe that scientists are inherently trustworthy, but your family and friends tell you that vaccines are unsafe, this is going to create some dissonance in your mind,” van der Does says. “We found that if you were already kind of anti-GM foods or vaccines to begin with, you would just move more towards that direction when presented with new information even if that wasn’t the intention of the intervention.”

The study suggests that targeting such people with science communication can be a challenge in that they will try to reduce their feelings. It might not be in the direction you think it will be. They could either accept scientific consensus with respect to scientific issues that are controversial among the public, such as vaccines and GM foods, or they could move further into conspiracy.

All in all, we found that network dissonance, belief change, and interdependence relate to each other over time, in line with our model assumptions. Interventions aimed at changing people’s beliefs led to a reconfiguration of beliefs that allowed people to move to lower network dissonance states and more consistent belief networks. However, these reconfigurations were not always in line with the objective of the intervention and sometimes even reflected a backlash.

And.

Individuals are motivated to reduce the dissonance between beliefs and reconfigure their beliefs to allow for lower dissonance. Such a reconfiguration can be, but is not necessarily, in line with the aim of the intervention. The direction in which individuals change their beliefs depends not only on the intervention but also on the easiest way for individuals to reduce their dissonance. This finding also goes beyond the classic finding that inducing dissonance leads to belief change (41–43) by showing that providing individuals with new information interacts with dissonances in their belief network. Individuals with low dissonance are unlikely to change at all, whereas individuals with high dissonance can change in both directions.

If this research holds up, we need to figure out how to identify people with a high degree of dissonance who won't reduce their dissonance in response to a pro-science message. How do we make it less likely that these people will change their beliefs in order to please us? It is clear that those who are the most certain are the most likely to change their opinions.

How can the results of the two studies be combined with what's already known? There are a couple of important points that I see. Steve has said that humility is important. Richard Feynman said, "The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool" Almost all of my colleagues have forgotten that I warned them.

People who follow my feed might have seen me say things like this recently.

Yep. The first step towards becoming a skeptic (and not a pseudoskeptic) is to admit to yourself—and really mean it—that you, too, can fall for these sorts of conspiracy theories and errors of thinkings. https://t.co/dgAs0GitTI

— David Gorski, MD, PhD (@gorskon) August 12, 2022

The moment you think you're immune to conspiracy theories, you're doomed. Unfortunately, a lot of self-identified movement skeptics—some quite prominent in the movement—seem not to have taken these messages to heart, especially lately about, for example, transgender medicine./end

— David Gorski, MD, PhD (@gorskon) August 12, 2022

I won't name those skeptics here, but the warning is applicable to people like John Ioannidis, who seems to think that he is immune to the same errors in thinking that lead others astray. There is a man who doesn't think that errors in thinking are important enough to trouble his massive brain with and who has expressed contempt towards those of us who do. It's easy to see how two men who built their academic careers on "meta-science" would think that they know better than the scientists with relevant topic-specific expertise.

There is also ideology involved. An example of this is Martin Kulldorff. He must have had libertarian views that were opposed to collective action. Based on how easy it was for Jeffrey Tucker to come to the headquarters of the American Institute for Economic Research, Kulldorff wanted the conference to be held there. Since then, Kulldorff and his fellow author Jay Bhattacharya have moved further and further into conspiracy theory and antivaccine advocacy.

Most of them weren't academic and some of them were already flirting with crankdom The attention they got for promoting views that went against the mainstream drew them into contrarianism. There isn't anything inherently wrong about challenging the mainstream. You have the evidence and logic to support the challenge. That is what makes legitimate scientists different from the cranks.

The role of grift can't be under emphasized. I like to say that ideology is important, but it's also about the grift. If you don't believe me, watch America's Frontline Doctors.

Science communication is more difficult than most people think, according to the studies. Predicting who will be persuadable and who won't react to science communication by moving deeper into conspiracy is not likely to happen if an antivaxxer is certain. I don't feel confident that I understand well the more I learn about it. Being willing to change one's views is the key. The application of the findings from these two studies is one of the biggest challenges for science communicators. It doesn't help that we're in the middle of a flu epidemic that has resulted in the spread of anti-science misinformation. The problem is made worse by the fact that a lot of the misinformation we see is promoted by actors with agendas.

I don't want to end on a bad note. The situation is not going to get better. The tools to counter antiscience messages are likely to be provided by this research.

You can buy an e- book.

Dr. Hall is teaching a video course.

The text is powered by the internet.

English

English