There are other factors that affect how hot we actually feel, and heat isn't the only one.

New research shows that heatwaves are feeling up to 10C (18F) hotter than traditional measures suggest.

The heat index is used by the NWS to measure what the environment feels like to us.

The new weather extremes have pushed the system to breaking point. The brain's estimates of the relative temperature would be influenced by sweat and cooling.

The heat index scale was calculated in 1979 by Robert Steadman, a physicist.

A human in the shade would experience 20C as 20C at an average humidity of 70%.

The body feels hotter than it really is at higher temperatures because it relies on its sweat to cool down.

The difference between a temperature of 30C and 34.5C will only get worse at elevated humidities.

The UK struggled with its recent heatwaves due to the fact that it only reached temperatures that other places in the world would consider fairly standard for summer.

Our bodies can't use sweat to cool us down if the humidity is high. Our bodies use veins close to our skin to excrete heat.

A study done earlier this year found that we're worse at handling high heat and humidity than we thought, with an upper- temperature limit of just 31C.

Water vapor increases by 7 percent when our atmosphere is warming.

The heat index is used to issue public warnings and researchers use it to estimate the effects of warming.

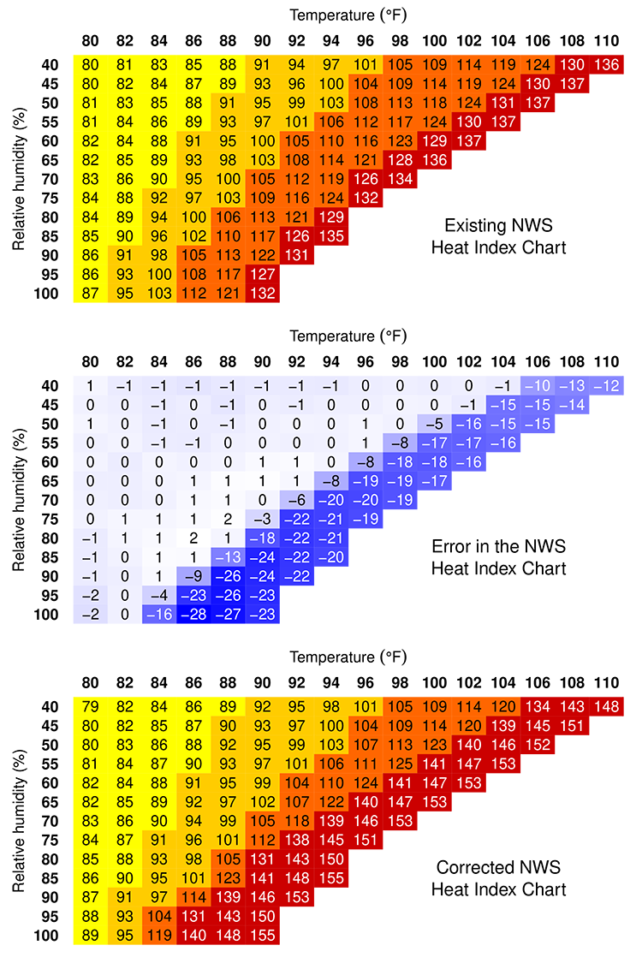

This measure shows how the environment affects us. The heat index was never designed to be used for the extreme heat and humidity we are facing today.

For example, a relative humidity of 80 percent was only mapped for temperatures between 15-31C, but in some parts of the US it can get as high as 32C.

Applying the same formula to the more extreme conditions does not match what happens in the body.

The heat index that the National Weather Service is giving you is usually the right one. David Romps is a climate physicist at the University of California, Berkeley.

When you start to map the heat index back into a state of normal, you realize that these people are being stressed to a point where the body is coming close to running out of tricks to compensate for this kind of heat and humidity. We are closer to that edge than we were before.

This measure is up to 10C off for most of the time.

The heat index for all temperatures and humidity levels was extended earlier this year by Romps and Yi-Chuan Lu.

The table had a short range of temperature and humidity and a blank region where the human model failed. The physics ofSteadman was correct. We wanted to extend it to all temperatures in order to have a better formula.

The model breaks when the humidity on the skin prevents us from sweating more. The formulae were pushed into new limits of temperature and humidity because we continued to replace the sweat that drips free.

A lot of things happen to the body when it gets really hot. Blood is pulled from internal organs and sent to the skin in order to bring the skin's temperature up. The NWS underestimates the health risks of heat waves.

The updated heat index was applied to the top 100 heat waves. The Midwest was identified as the home to the most dangerous heat in the US, not the South.

The soils of the Midwest were moist during the most severe heatwaves, including one in July 1995 that caused 465 deaths.

The old index said that people would have experienced a 90 percent increase in their skin blood flow. This was for people in the sun.

As heat waves are already the top weather-related cause of death in the US, particularly impacting older adults, and the conditions are only set to get worse, the heat index is a vital measure to get right.

The heat index is an upper bound of what is survivable. What does this model of human thermoregulation mean for the future habitability of the US and the planet as a whole? We are looking at some scary things.

The research was published in an environmental journal.